[ad_1]

Last time, we talked about the overwhelming climate shockThis was the fate of Europe in 1709. Extreme cold and heavy rainfall caused widespread famine, plague and other miseries across Europe. These conditions continued for the next decade. Millions perished. People turned to religious explanations for the crisis given the circumstances. God was clearly angry and was punishing his straying subjects. This kind of crisis can only lead to religious scapegoating. The best example is in England. The story ultimately boils down to how climate is considered in religious and political history.

This is the background. English Protestants were split since the 1660s between members of Church of England who accepted episcopacy or the Prayer Book and those who rejected these things. These dissident groups were called Nonconformists and Dissenters depending on their traditions. Although they suffered from severe civil disabilities, they were not generally persecuted and worshiped openly. One of England’s two great parties, the Whigs, favored extending toleration for Dissenters, as they were faithful allies against Catholicism, and against France. The other party, the Tories, was militantly High Church, in a political rather than liturgical sense, and they favored strong privileges and power for the established church.They raged especially against Nonconformists who engaged in Occasional Conformity – that is, deigning to take the Anglican Communion sporadically, solely in order to qualify for establishment status. Such hypocrisy was denounced as “playing bo-peep with God Almighty.” What made this situation deadly dangerous was that the Queen, Anne, had no male heir. The legitimate successor to her estate according to struct principles would be James Stuart, an exile who was militantly Catholic and closely associated with the French court. (His son would be a Catholic Cardinal. Parliament ruled that the Hanoverian Protestant would be the real successor. By 1709, however, things were open with civil war and rebellion very likely. The country’s very existence as a Protestant nation was at stake.

The Whigs won 1708 elections well, but they were harshly attacked by the Tory. The government had to extort every penny from the population through taxation in order to finance the war against France. The economy crashed during 1709 and people were more and more desperate, more at risk from hunger and extreme cold. They were willing to listen to any demagogue.

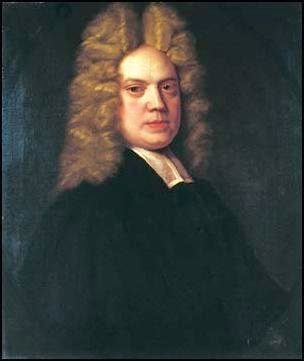

An Anglican clergyman named “Fear and Rage” displayed fear and rage. Henry SacheverellHe preached his incendiary sermon in November 1709, which he did in November 1709. The Perils of False Brethren. This date is crucial. It is critical. According to the nursery rhyme,

Remember / The fifth November / Gunpowder and treason.

I see no reason/ Why gunpowder traitory / Should ever forgotten.

Modern Bonfire Night festivities involve ritual burnings of “Guys,” who represent the lead plotter, Guy Fawkes. Sacheverell’s sermon for the day nodded to the Catholic menace, but devoted virtually all its time to an extremist attack against the government, the Whigs, and the Dissenters. He directly attacked any notions of toleration or liberty of conscience, and implied that the Queen’s government endangered the Church by its excessive gentleness towards those Dissenters and Occasional Conformists. They were the ones really threatening treason and plot – and who knows, gunpowder too.

The sermon was not considered outright sedition if it was interpreted strictly. The government foolishly tried to suppress the sermon by publicly condemning it and trying Sacheverell before Parliament – technically, by impeaching him. Although he was convicted, the event made him a national hero and his travels around the country became something of a royal progres. Extreme High Church radicalism became the norm. Even among faithful Anglicans, a sizable minority moved to supporting the candidacy of the Catholic James as successor – hence the name Jacobites, from the Latin form of James. This was a very dangerous situation, and it threatened treason or insurrection.

Protests for Sacheverell morphed into national rioting and violence against Dissenters & Whigs as urban mobs targeted their houses and institutions. Popular unrest reached its peak at the end Winter (late February to early March), when people were trapped so long by the horrible cold that they couldn’t move and were forced to eat the last of their preserved food. They were hungry and in desperate need of food and had to find out who in the society had so irritated God that they needed to be snuffed out. At various times through history, the culprits might have been Jews or Catholics, but on this occasion, it was the Dissenters – the Presbyterians, Baptists and others.

I quote Wikipedia:

London saw rioting. On the evening of March 1, protestors attacked an elegant Presbyterian meeting-house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, built only five years earlier. They smashed windows, tore down the roof tiles, and tore apart the wooden fittings inside, which they turned into a bonfire. The crowd then marauded through much of the West End of London chanting “High Church and Sacheverell.” It spread across the country, notably in Wrexham, Barnstaple and Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, where Presbyterian meeting-houses were attacked, with many being burnt to the ground.

When new elections were held that Autumn, the Tories won a massive victory on the strength of the “Sacheverell Wave”, and the polarization between the parties grew acutely.

One interesting sidelight. I have spent a lot time reading the family papers of different aristocratic and gentleman families during this period, particularly their political and personal correspondence. If you sort the letters according to year, you will notice that in many cases the numbers plummet around 1712-15. Either lots of people developed sudden writers’ cramp, or else they were being doubly careful to burn anything that might seem remotely seditious. We do know that many prominent figures corresponded to the exiled Jacobite court, regardless of how openly treasonous. They tried to keep their options open at the minimum. On the other hand, we know that the elite Whigs were seriously considering their own plans for violent action if they were to restore the Stuart dynasty.

It is almost miraculous that Queen Anne, who died in 1714 at the age of 62, was succeeded peacefully, by George I, a German Protestant heir and, thus, by the Hanoverian family. Civil war and state failure remained a viable possibility. Widespread demonstrations called once more for “Sacheverell and High Church.” Some militants overtly cried Jacobite slogans, praising “High Church and Ormonde” – Ormonde referring to the Duke who was seen as the Jacobite leader. Some mobs called for the death of the new King George. The Jacobites launched an unsuccessful, but effective insurrection in 1715.

The blustering savagery displayed by the Sacheverell movement made imaginable that even the most sympathetic government would relax the restrictions on Nonconformists. These restrictions remained in effect for at least another century in Britain. The conditions were far more appealing in the American colonies.

I don’t believe that the party crisis of these years could have been avoided if there had been a different climate. Without that climate element, it is difficult to understand both the extreme depth and sheer toxicity in religious/political hatred during these years, as well as their political consequences.

[ad_2]