[ad_1]

Zuma Press

This story was originally published in Yale E360 and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Thirty years agoNorth Carolina was the first country to have the largest hog slaughterhouse. Duplin and Sampson in eastern North Carolina became synonymous with environmental racism after it was revealed that hogs outnumbered the residents of these largely Black, American Indian and Latino counties 40 to 1.

But even here in North Carolina, in America’s most densely populated swine areas, hog is no longer the boss of industrial farming. After massive expansion in recent years, poultry now trumps pig production in scale and economic impact and is increasingly seen as a threat to the environment and human health, chiefly because of the runoff of poultry waste into the state’s waterways.

North Carolina farmers produce more than 500,000,000 chickens and turkeys annually than the 9 million hogs. It is difficult to estimate the number of industrial-scale poultry farms because there is not an official state record of where they are located. The Environmental Working Group (EWG), which uses satellite imagery and aerial surveillance to identify facilities across 17 watersheds in the State, has the best available data.

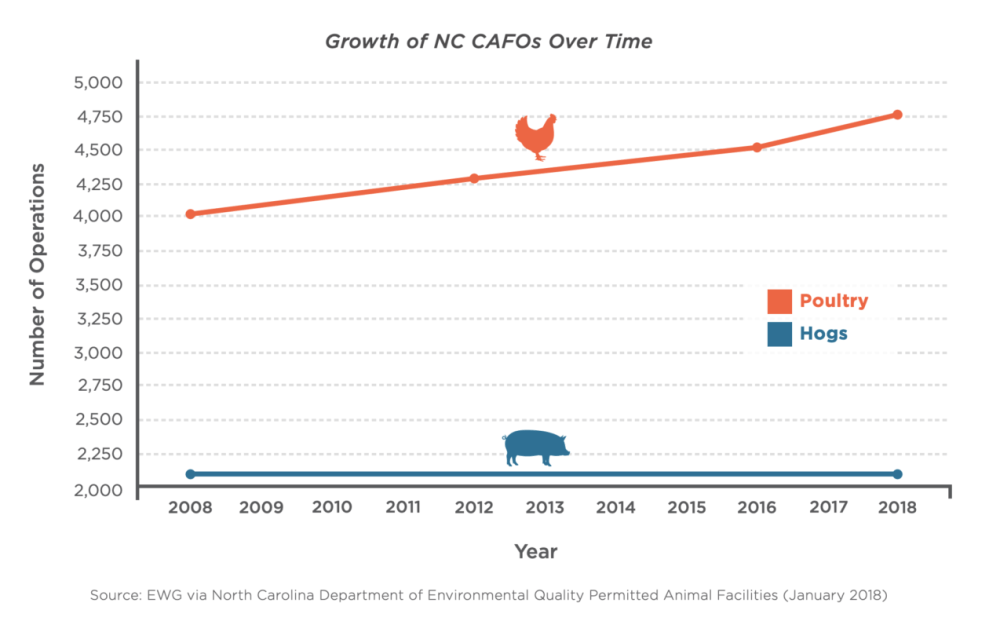

A Joint report with the Waterkeeper Alliance revealed expansion at a breakneck pace, with poultry operations steadily spreading west from their original stronghold in the eastern part of the state. From 2008 to 2016, the state added about 60 new poultry farms each year. That number doubled between 2016 and 2018, with more than 120 poultry farms added annually, and in 2020 roughly 1,000 new large-scale poultry operations were added. The state now has more than 6,500 poultry CAFOs, nearly triple the number of hog farms. This boom happened because of a quirk in state law that leaves the poultry industry largely unregulated, particularly in terms of the waste its farms generate.

For years, environmentalists were focused on the vast amount of liquid feces and urine generated by North Carolina’s hog farms—an estimated 10 billion gallons—and held in large, unlined lagoons. Sprayed onto fields or spilling out in large quantities during floods or hurricanes, the waste fouls groundwater, streams, rivers, and lakes with excess nutrients and other pollutants.

Increasingly, however, the state’s environmental groups are concerned about the mountains of chicken waste stored on poultry farms and also spread over fields. Although chicken waste is dry, it nevertheless makes its way into the state’s waters. The EWG-Waterkeeper report estimates that North Carolina poultry farms produce about five million tons of waste annually—about five times more waste (and an estimated five times more nitrogen and four times more phosphorus) than hog farms.

The US Environmental Protection Agency says agricultural waste from poultry and hog CAFOs threatens air and water quality, aquatic life, biodiversity, and human health. Nutrient-fed algal blooms greatly reduce or eliminate oxygen in the water, harming or killing fish. The blooms also elevate toxins and bacterial levels that can leach into water and can cause gastrointestinal illnesses, skin reactions, and neurological effects in people. No extensive studies have been done on the impacts of poultry CAFO runoff on groundwater in North Carolina, but the EPA has said that animal waste is a primary source of nitrogen and phosphorous pollution through surface runoff and infiltration.

The poultry industry has been involved in several high-profile disasters in North Carolina. Several million chickens and turkeys drowned in 2016 when Hurricane Matthew dumped more than 15 inches of rain on the state’s coastal plains. Two years later, flooding from Hurricane Florence killed another 3.4 million birds and washed the ammonia-rich litter into waterways. A study conducted by the Nature Conservancy and researchers at the University of Arizona found that heavy rainfall from these two hurricanes flooded 36 poultry CAFOs and 91 hog CAFOs.

Growth of North Carolina CAFOs since 2008.

Environmental Working Group / Waterkeeper Alliance

In both instances, the North Carolina Department of Agriculture asked the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for tens of millions of dollars for cleanup and to compost the dead birds. Yet state regulators have not acted on calls for more oversight from environmental groups and farm neighbors.

“The biggest problem with the poultry industry is we don’t know what we don’t know because there is zero transparency,” says Katy Hunt, the Neuse Riverkeeper. “You can go to the [state] DEQ [Department of Environmental Quality] website and download a list of every permitted hog or dairy CAFO in the state. You can’t do that with poultry because DEQ doesn’t even know where the facilities are located. I’ll do a flyover of my basin to keep an eye on things and look for violations. If I fly the same route two months in a row, new poultry facilities will have sprung up in that short time.”

When the last significant amendments to farm regulations in North Carolina were made more than 25 years ago, all animal farming operations functioned without a permit. That changed in the wake of several high-profile and economically threatening incidents at hog operations. In 1996, 22 hog waste lagoons overflowed following Hurricane Fran. Three years later, floodwaters from Hurricane Floyd breached the lagoons again. Suddenly, images of dead hogs floating in rivers of toxic waste were everywhere. The pollution created along the coast also threatened tourism and commercial fishing, significant parts of the state’s economy.

That led the General Assembly to place a moratorium on hog farm expansion and change what had been a permitless system to one that required permits for every type of industrial farm—except poultry. Despite being the number one agricultural commodity in the state and generating the highest volume of waste, poultry could continue with business as usual. That’s because the industry had three things going for it: Unlike swine, it kept a low profile. It produced dry litter. And, at the time, it hadn’t experienced any negative headline-grabbing incidents.

A poultry facility in eastern North Carolina. Piles of waste are visible to the right of each building.

Cape Fear Riverkeeper

Agricultural runoff is exempt from the Clean Water Act, but federal law does require a permit for operations that discharge into US waters from a point source. North Carolina law, however, makes a distinction between liquid and dry waste operations. Only animal operations that produce liquid waste need a permit. The dry waste from poultry is therefore exempt from all permitting requirements. Without any such restrictions, poultry farmers could set up shop anywhere in the state. And they did. Anyone can start a poultry operation—anyone, that is, who can get a contract with a major poultry producer and come up with about a million dollars in startup costs.

Environmentalists say Republican lawmakers, particularly those from eastern North Carolina, view themselves as guardians of the poultry and swine industries. They write laws to shield farmers from scrutiny and protect their economic interests, often, advocates say, at the expense of citizens and the environment.

“Whenever one of these bills come up, [Republican Rep.] Jimmy Dixon always says something like, ‘Well, I don’t know where you’re going to get your food from?’” said Democratic State Representative Craig Meyer. “The answer is we’re going to get our food from farms that don’t pollute our water!”

Larry Baldwin, who was riverkeeper for the Lower Neuse and Crystal Coast and is now the Waterkeeper Alliance’s campaign coordinator for Pure Farms, Pure Water, said, “The poultry industry has been flying under the radar for many years. But with the influx of [new companies] and the other ones trying to grow, the poultry waste issue is as big, if not bigger, than the hog waste issue.”

The North Carolina Poultry Federation did not respond to requests for comment. In previous interviews, Executive Director Robert Ford has disputed the notion that farmers dispose of the waste by overusing it as fertilizer. “If you’re in the chicken business … that poultry litter has some pretty good value for you,” Ford said in a 2019 interview with TV station WRAL. “They’re not going to over-apply it, because it’d be a waste of money.”

“Farmers get a black-eye a little bit,” Ford told Environmental Health News in 2019. “They do care about the water, that’s their livelihood, they drink the water too.” He said that North Carolina’s poultry industry generates $36 billion in direct and indirect economic impact, creates 125,000 jobs, and makes up roughly 40 percent of the state’s total farm income.

North Carolina has 15 riverkeepers, more than any other state in the country. They view pollution from poultry and hog CAFOs as the greatest threat to the state’s water quality. “If they’re barely doing any enforcement over a more-regulated industry [hog farming], how can we possibly expect them to do any enforcement at all over a different industry that has almost no regulations?” says Hunt.

The riverkeepers routinely do aerial and on-the-ground inspections of CAFO impacts, photographing suspected violations and sending them—along with a timestamp and GPS coordinates—to the DEQ. By law, the agency cannot cite or fine a farm based on third-party information, but they are supposed to investigate the claims, which the riverkeepers say rarely happens.

Rather than responding to specific questions, DEQ spokesperson Josh Kastrinsky referenced the agency’s responsibilities and guidelines, which note that “dry-litter” poultry operations in the state do not need a permit to operate and “do not submit any forms or documentation and do not register with the Division of Water Resources.”

A riverkeeper samples water near a poultry farm in the Catawba River Basin.

Catawba Riverkeeper

Brandon Jones is the Riverkeeper for the Catawba Basin, which spans 3,300 square miles from the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the South Carolina border. Its 9,400 miles of waterways provide drinking water for more than 2 million people. An increasingly large part of Jones’ job is monitoring the basin’s roughly 700 industrial poultry facilities—housing a total of 40 to 60 million birds—and their impacts on the region’s water quality.

On the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, I follow Jones on his monthly trek to collect water from 10 sites. Eight sites are downstream of poultry CAFOs, and two are control sites for comparison. Our first stop is about an hour northwest of Charlotte in the Sugar Loaf township of Alexander County. The farms aren’t visible from the road, but as soon as I exit my car, I am hit by the overwhelming, noxious smell of chicken poop.

“Yeah, it smells pretty bad,” he says. “That’s a sign that they’ve recently been cleaning out the barns or spreading litter on the crops. This isn’t really about fertilizing. It’s just about getting rid of the waste.”

We make our way through brambles and briars and down into a ravine to sample runoff from a nearby stream. He dips a probe into the water to measure temperature, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and pH levels. He then takes the samples back to the lab for evaluation and posts the results online a few days later. Five of the eight sites downstream of dry litter spreading fields had high levels E. coli bacteria.

“We have documented almost 600 violations for those litter piles and storage and nothing has changed,” says Jones. “We don’t really know what’s going on with these operations because there’s no public records, no accountability or inspections. The process is very sketchy and not at all transparent.”

Piles of poultry waste at a chicken farm in North Carolina.

Rick Dove/ Waterkeeper Alliance

On a flyover with Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette, it’s hard at first to distinguish a poultry operation from a swine operation. Both house the animals in uniform rows of slender, steel-roofed barns; hogs are jammed into the facilities by the hundreds, and poultry are caged in groups of 30,000 to 35,000. But poultry farms lack lagoons, the Olympic-sized swimming pools of hot-pink liquid hog manure that gets sprayed on fields as fertilizer.

Poultry farms handle their waste differently. Several times a year, the chicken and turkey farmers clean out the barns and scoop the dry litter into massive piles to later be used as fertilizer. From a distance, the mounds look like innocuous hay bales or dirt, but they also contain dead birds, heavy metals from the poultry feed, antibiotics, and potentially harmful bacteria like E. coli and salmonella.

“The rule is you can’t leave dry litter uncovered for more than 15 days, because every time it rains all that stuff is just running off,” Burdette explains. “We’ve seen piles left uncovered for months and months, so they totally disregard those rules. But even those tarps don’t really stop anything. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound.”

While the number of poultry farms in North Carolina continues to expand, the producers have consolidated in recent years. Just four companies process the majority of chicken sold in the United States—Tyson Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Sanderson Farms, and Perdue Farms. These poultry giants subcontract the production of chickens and turkeys to hundreds of operators, with the corporations dictating the types of birds raised, what they are fed, when and what antibiotics they receive, and when they’re slaughtered. Waste management, however, is the farmers’ sole responsibility. Most spread it nearby, oversaturating the land and risking runoff to nearby waterways.

Baldwin, the CAFO coordinator of the Waterkeeper Alliance, points to Mississippi-based Sanderson Farms as the catalyst for most of the state’s new poultry operations, the overwhelming majority of which are located in low-wealth, disproportionately Black, Latino, and American Indian communities. One five-year-old Sanderson poultry complex, in the tiny town of St. Pauls in Robeson County, is a $155 million, 180,000-square-foot operation that debones and processes 1.25 million birds a week and sells roughly 500 million pounds of “dressed poultry” a year. The company says it employs more than 1,000 people in a low-income area, not including 80 contract farmers who grow the chicken.

Robeson is one of the poorest counties in the state, its population 42 percent American Indian and 24 percent Black. The county is already burdened by pollution from textile plants, landfills, and hazardous waste sites, and environmentalists are trying to stop Active Energy, a UK-based biomass company, from building a wood pellet factory there. While the county somehow avoided having the industrial hog farms that define neighboring Duplin and Sampson counties, the three-county region has recently become the epicenter of poultry production, producing 113 million chickens and turkeys in 2019.

Anthropologist David Shane Lowry, a distinguished fellow in Native American Studies at MIT, moved with his family to Robeson County when he was 10 years old. He left for college in 1999 but returns regularly. Over the last decade, he has noticed dramatic changes in his community. There are more and bigger chicken houses, flies as thick as bees near a honeycomb, and deforestation to make room for natural gas pipelines and poultry infrastructure. And, of course, the smell. “There would be this smell of urine in the air that was very acidic to your nostrils,” recalls Lowry. “Whenever we complained, my wife’s father would make jokes about it. He’d say ‘That’s just the smell of farming and making money.’”

Drowned chickens at a farm in Duplin County, North Carolina, after Hurricane Florence in 2018.

We Animals Media.

Ryan Emanuel, an associate professor at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, is a native of Robeson County and a scholar on water, environmental justice, and Indigenous rights. He’s says he’s seen this scenario more times than he cares to remember:

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s CAFOs or power plants or something else, the script I’ve seen play out time and again is always, ‘Look over here at jobs. Don’t look over here at the pollution or over here at the health impacts.’ It’s as if you can throw out a number of jobs that will make it okay to expose people to a certain level of harm.”

Conservationists, environmental groups, and some state legislators have been pressing for more government oversight and enforcement of the poultry industry for years, but the proposals don’t make it out of the Republican-controlled agriculture committee. Three years ago, then-State Senator Harper Peterson, a Democrat, requested funding to conduct a Study to determine the environmental and human health impacts of dry poultry litter. The request was rejected. Republican State Senator Tom McInnis, an ardent supporter of the farming industry, voiced his objection: “I like fried chicken on Sunday.”

Ricky Hurtado, a freshman Democratic State Representative, introduced HB 913 (Poultry Waste Reporting) last May. This bill would require any farmer who has 30,000 or more birds to submit an annual animal waste management plan that meets all testing and record-keeping requirements. The bill has not been given a hearing.

“Their silence is the action,” Meyer says of the Republicans that support the industry. “They are more defensive of current farming practices than they are of people’s ability to drink clean water.”