[ad_1]

Back in November 2019, before the pandemic began, would you have guessed how important videoconferencing like Zoom would be in people’s lives just a few months later?

That’s the kind of challenge economists face when they try to put a single number on the long-term cost of mitigating climate change or the cost of allowing global temperature to keep rising. As technology advances and new policies are implemented, human behavior changes.

I am a microeconomist and investigate the Climate change: The causes and consequences. When I think about the climate change challenge in 2040 and beyond, I anticipate many “known unknowns” about our future. Thus, I am amazed to read precise climate cost estimates like those recently published by economic consultants McKinsey & Co.

McKinsey projects the global cost for transitioning energy and other industries to net-zero emission by 2050 A year of US$9.2 trillion. Swiss Re, the insurer, has estimated that Doing nothing will not workGlobal GDP to grow by as much as 14% (or approximately $23 Trillion) by 2050

These numbers are widely used to motivate governments, companies, and individuals to take action. Economists agree that climate changes, if left unchecked will cause economic harm. These estimates are based on formal models that include many assumptions. Any one of these assumptions could throw off the accounting in big ways, leaving estimates either wildly high, or very low.

While people might think they want “precision,” precise predictions Increase the possibility of conveying too much certaintyIn a constantly changing world. Here’s what goes into climate economic models and why certainty isn’t an option for future cost projections.

The prediction challenge

Climate economic modelsAnswer several prediction questions like:

-

“How will the performance of the world economy be affected if we enact a carbon dioxide tax today?” The answer to this question helps us to understand the “cost of taking action.”

-

“If the entire world does enact this carbon tax, how much will greenhouse gas emissions decline by in each subsequent year?”

-

“What will we gain economically by reducing our greenhouse gas emissions?”

-

“What will be the economic and quality-of-life impact if we do nothing and just allow greenhouse gas emissions to rise under ‘business as usual’?”

To answer these complex questions, climate economists make a series of assumptions that are “baked” into their mathematical models.

Unknown facts

First, economists must predict the world’s average income per person for each year in the future.

Macroeconomists face challenges Predicting the timing and duration recessions. Predicting the future Economic growth over the period of 30-40 years requires predicting how the quantity and quality of the world’s workforce and our technology will evolve over time. Predicting the world’s population growth is also a challenging exercise, as increases in Urbanization, women’s access to educationAll improvements in birth control are associated with a reduction in fertility.

Second, they need to make an informed guess as to the future technologies that will be available for power generation and transportation. They can calculate how much additional greenhouse gas emissions the world will produce each year if they can accurately predict the future population, income, and technology.

They use a climate science model for estimating the additional climate change risk posed by greenhouse gas emissions. This is usually measured by an increase in the world’s average surface temperature.

Fourth, they must take a stand on how our future economy’s production will be affected by rising climate change risk. Idealerweise, these models will also reveal how more greenhouse gas emissions would affect the economy. Potential for disaster scenarios.

A research team can combine all these equations with their respective assumptions to generate a single number, such as: $23 trillion in global climate change damages if we don’t take serious steps to reduce emissions.

The ‘art’ of predicting future emissions

Economists estimate future global greenhouse gas emissions by multiplying the predicted global gross national product – the total value of goods and services – by the average emissions per dollar of gross national product.

If the world can eliminate fossil fuel use, then this figure could be very close to zero. The innovation and deployment of low-carbon technologies – think electric vehicles and solar farms – can significantly shift the costs and benefits that economists are trying to quantify.

There are many factors that determine the path of technological progress, including investment in research-and-development. International politics also don’t always factor into climate economic models. For example, China could choose to become more isolated and increase its coal consumption, as it is rich in coal. Could it be the reverse? China decides to use its powerful state to push the green tech sector to create a booming future export market that greens the world’s economy?

Future climate change impacts forecast

Economic mathematical models boil down the impact of climate change into a single algebra equation called the “climate damage function.” In my book “Adapting to Climate Change,”I will give you several examples of why this function is constantly changing and therefore very difficult to predict.

Many companies, for example, are expanding. climate risk ratings systemsReal estate buyers need to be educated about the various climate risks specific pieces will face in the future.

Let’s say that the emerging climate risk rating industry makes significant progress in identifying safer places to live. Zoning codes can be changed to allow more people access to these safer areas. The damage that Americans suffer from climate change would decrease as people literally “move to higher ground”.

This dynamic cannot be captured with rigid algebra by the confident climate modeler.

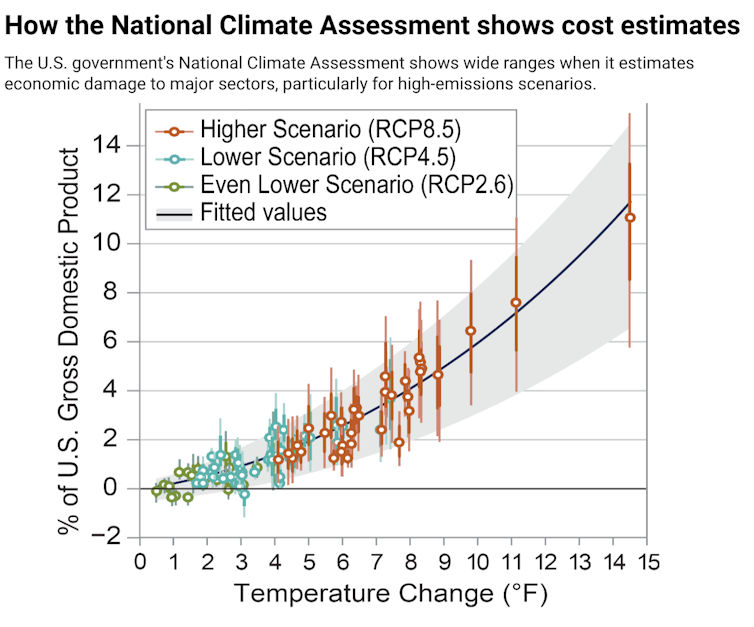

Source: Fourth National Climate Assessment

Prediction under uncertainty

Climate economics models can play a “Paul Revere” role – educating policymakers and the public about the likely risks ahead. These models are built by economists. Honest about their limitations. A model that generates “the answer” may lead decision-makers astray.

As much as everyone might like a concrete answer to how much climate change and acting on climate change will cost, we’ll have to live with uncertainty.

[More than 140,000 readers get one of The Conversation’s informative newsletters. Join the list today.]