[ad_1]

It was the mid-1980s, at a meeting in Switzerland, when Wally Broecker’s ears perked up. Hans Oeschger, a scientist, was talking about an ice core that was drilled at a southern Greenland military radar station. Layer by layer, the core of 2 kilometers length revealed the climate like thousands of years back. Climate shifts, inferred from the amounts of carbon dioxide and of a form of oxygen in the core, played out surprisingly quickly — within just a few decades. It seemed almost too fast to believe.

Broecker returned home, to Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and began wondering what could cause such dramatic shifts. Some of Oeschger’s data turned out to be incorrect, but the seed they planted in Broecker’s mind flowered — and ultimately changed the way scientists think about past and future climate.

Broecker was a geochemist and oceanographer who suggested that the abrupt change in the North Atlantic climate could be caused by the closing of a major ocean flow pattern. He named it the great ocean conveyor. Broecker argued that melting ice sheets had released large pulses of water into North Atlantic oceans in the past. This made the water more fresh and stopped circulation patterns that depend on salty water. The result was a sudden atmosphere cooling that plunged the entire region, including Greenland into a big chill. (In the 2004 film Tomorrow is Tomorrow(Ice, a dramatic oceanic shutdown covers the Statue of Liberty.

This was a breakthrough of insight that was unprecedented at the time. Most researchers were still unsure if climate could shift abruptly and ponder how.

Broecker was not only able to explain the changes observed in the Greenland Ice Core, but he also created a new field. He persuaded, cajoled, and brought together other scientists to study how the climate system could change on a dime. “He was a really big thinker,” says Dorothy Peteet, a paleoclimatologist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City who worked with Broecker for decades. “It was just his genuine curiosity about how the world worked.”

Broecker was the son of a fundamentalist family, who believed that the Earth is 6,000 years old. Broecker was not the best candidate to become a groundbreaking geoscientist. He relied on visual aids and conversation to absorb information because of his dyslexia. He was a radiocarbon dating expert, but he never used computers. He worked tirelessly to understand all aspects of the Earth system, including the oceans, the atmosphere, and the land, contrary to the siloing that is common in science.

In the 1970s scientists realized that humans were adding excess carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels and reducing carbon-storing forest. those changes were tinkering with Earth’s natural thermostat. Scientists knew that climate had changed over time. Geologic evidence spanning billions of years showed hot, dry, cold, or wet periods. But many scientists focused on long-term climate changes, paced by shifts in the way Earth rotates on its axis and circles the sun — both of which change the amount of sunlight the planet receives.1976 paper with great influence referred to these orbital shifts as the “pacemaker of the ice ages.”

Antarctica Ice cores Greenland was the change in the game. 1969. Willi Dansgaard, University of Copenhagen, and his colleagues. reported resultsA Greenland ice core containing the last 100,000 years. They discovered rapid fluctuations in oxygen-18, which suggested wild temperature swings. Climate could oscillate quickly, it seemed — but it took another Greenland ice core and more than a decade before Broecker had the idea that the shutdown of the great ocean conveyor system could be to blame.

Broecker suggested that such an event was responsible for the 12900 year-old cold snap. As the Earth emerged in its orbitally influenced Ice Age, water melted from the northern ice sheet and washed into North Atlantic. He said that the ocean circulation stopped, causing Europe to feel a sudden chill. The Younger Dryas, which lasted just more than a millennium is named after an Arctic flower, which thrived during the cold snap. It was the last hurrah for the last ice age.

Evidence that an ocean conveyor shutdown could cause dramatic climate shifts soon piled up in Broecker’s favor. For instance, Peteet found evidence of rapid Younger Dryas cooling in bogs near New York City — thus establishing that the cooling was not just a European phenomenon but also extended to the other side of the Atlantic. The changes were rapid, widespread, and real.

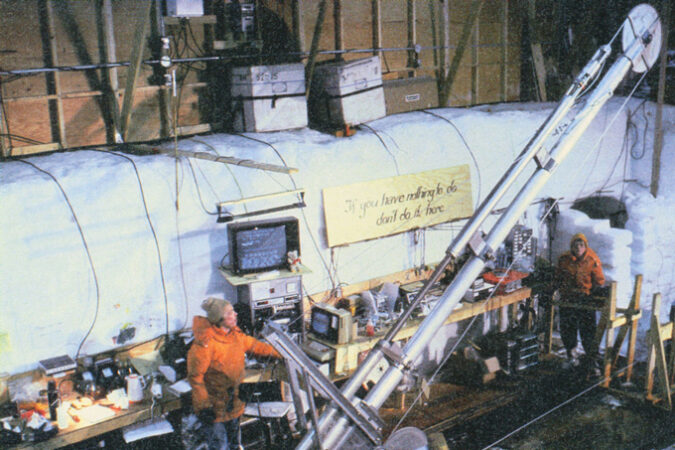

By the late 1980s and early ’90s, there was enough evidence supporting abrupt climate change that two major projects — one European, one American — began to Drill two new coresIn the Greenland Ice Sheet. Richard Alley, a Penn State geoscientist, recalls working through layers and documenting small climate changes over thousands of year. “Then we hit the end of the Younger Dryas and it was like falling off a cliff,” he says. It was “a huge change after many small changes,” he says. “Breathtaking.”

Sign up to receive the latest from Science News

Summary and headlines of the latest Science NewsDelivered directly to your mailbox

We are grateful that you signed up!

Signing up was difficult

The scientific recognition of Greenland’s new cores has been confirmed by scientists. Climate change is sudden. Although the ocean conveyor’s shutdown could not explain all climate changes, it did show how one physical mechanism can cause massive disruptions on the entire planet. It also opened up discussions about how quickly climate may change in the future.

Broecker, who was killed in 2019, spent his last years exploring the sudden shifts that were already occurring. For example, he worked with Gary Comer (a billionaire) to find new directions in climate research and solutions.

Broecker knew more about the future than anyone. He often described Earth’s climate system as an angry beast that humans are poking with sticks. And One of his most well-known papers was titled “Climatic change: Are we on the brink of a pronounced global warming?”

It was published in 1975.