[ad_1]

Some of the world’s most ancient buildings are being destroyed by climate change, as rising concentrations of salt in IraqYou can eat away at mud brick, and more frequent sandstorms will erode ancient wonders.

Iraq is the birthplace of civilisation. It was here that agriculture was born, some of the world’s oldest cities were built, such as the Sumerian capital Ur, and one of the first writing systems was developed – cuneiform. The country has “tens of thousands of sites from the Palaeolithic through Islamic eras”, explained Augusta McMahon, professor of Mesopotamian archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

Sites such as the legendary could be damaged Babylon “will leave gaps in our knowledge of human evolution, of the development of early cities, of the management of empires, and of the dynamic changes in the political landscape of the Islamic era”, she added.

The land between the two rivers in modern-day Iraq is Mesopotamia. It is rich in salt (munSumerian) salt that is naturally found in soil and groundwater. Cuneiform texts describe salt collection and its use in everything from food preservation to healthcare and rituals. There is a Sumerian proverb that says the basic necessities of life are bread and salt: “When a poor man has died, do not revive him. He was deprived of salt when he had bread. When he had salt, he had no bread.”

Salt in the soil can aid archaeologists in some circumstances, but the same mineral can also be destructive, and is destroying heritage sites, according to the geoarchaeologist Jaafar Jotheri, who described salt as “aggressive … it will destroy the site – destroy the bricks, destroy the cuneiform tablets, destroy everything”.

The destructive power and dangers of salt are increasing because of water shortages caused both by the construction of dams upstream by Turkey/Iran and years of poor management of water resources in Iraq.

“The salinity in Shatt al-Arab river started to increase from the 90s,” said Ahmad N A Hamdan, a civil engineer who studies the quality of the water in Iraq’s rivers. In his observations, the Shatt al-Arab – formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates – annually tests poor or very poor quality, especially in 2018, which he called a “crisis” year when brackish water sent at least 118,000 people to hospital in southern Basra province during a drought.

Climate crisis is a contributing factor to the problem. The climate crisis is making Iraq hotter and more dry. The United NationsThe average annual temperature will rise by 2C by 2050, with more days of extreme temperatures exceeding 50C. Rainfall will fall by as much 17% during the rainy seasons. Sand and dust storms will increase by more than twice the rate of 120 per year to 300. Rising seawater is pushing salt up into Iraq. In less than 30 years, some parts of southern Iraq may be under water.

“Imagine the next 10 years, most of our sites will be under saline water,” said Jotheri, a professor of archaeology at Al-Qadisiyah University and co-director of the Iraqi-British Nahrein Network researching Iraqi heritage. About a decade ago, Jotheri noticed salt damage to historic sites.

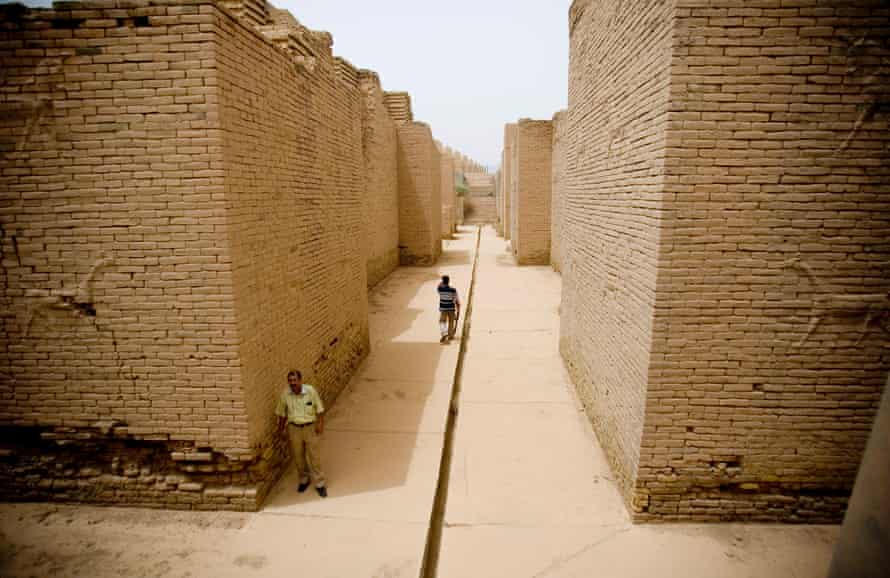

Unesco-recognised Babylon is the capital of Babylonian Empire. Here, a salty sheen covers 2,600-year-old bricks made of mud. The walls are crumbling at the base of the Temple of Ishtar. This is the Sumerian goddess love and war. Salt accumulates in the wall’s depths until it crystallizes, cracking the bricks, and causing them to fall apart.

Other affected sites include Samarra, an Islamic-era capital that has a spiral minaret and is being eroded in sandstorms, as well as Umm al-Aqarib, which has its White Temple, palace, and cemetery that is being swallowed by the desert.

Iraq lost a significant part of its cultural heritage in this year. 150km south-east of Babylon is a salt bed that once belonged to Sawa Lake. The spring-fed water housed at least 31 species, including the grey herons and the ferruginous ducks. It is now completely dry as a result of climate change and overuse of water by nearby farms. Farmers can drill wells and plant wheat in the dusty desert landscape without any regulation.

“When I was a child I remembered that Sawa Lake was a big lake, a large lake. It looked like the ocean. But now it’s gone. It is gone. We don’t have any lake any more,” said Jotheri.

Sawa will be another source of sandstorms as desert plants are now growing where once there was water.