[ad_1]

The COP26 UN climate talks have ended in Glasgow and the final word has been given on the Glasgow Climate Pact, which was signed by all 197 countries.

If you are interested in the 2015 Paris AgreementThe framework was established for countries to address climate change. Six years later, Glasgow was the first major test of the high-water mark in global diplomacy. So what have we learnt from two weeks of leaders’ statements, massive protests and side deals on coal, stopping fossil fuel finance and deforestation, plus the final signed Glasgow Climate Pact?

Here are the facts about transitioning from coal to carbon market loopholes.

1. There has been some progress in reducing emissions, but not enough.

The Glasgow Climate Pact represents incremental progress, not the breakthrough moment required to stop the worst effects of climate changes. The UK government as host and therefore president of COP26 wanted to “keep 1.5°C alive”, the stronger goal of the Paris Agreement. But at best we can say the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is on life support – it has a pulse but it’s nearly dead.

The Paris Agreement says temperatures should be limited to “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and countries should “pursue efforts” to limit warming to 1.5°C. Before COP26 the world was on track for 2.7°C of warmingBased on the commitments made by countries and the expectation of technological changes, Some key countries have reduced this by making announcements at COP26, including new pledges of reducing emissions in the next decade. best estimate of 2.4°C.

More countries have also announced long-term net zero goals. One of the most important was India’sThe pledge to achieve net zero emission by 2070. Critically, the country stated that it would quickly expand renewable energy to account for 50% of its total consumption in the next ten year, reducing its emissions by 1 billion tonnes in 2030 (from 2.5 billion at the moment).

Fast-growing NigeriaAlso, pledged net zero emissions by 2020 Countries that account for 90% of the world’s GDPWe have now committed to going net zero by mid-century.

Santos Akhilele Aburime / shutterstock

A world warming by 2.4°C is still clearly very far from 1.5°C. What remains is a near-term emissions gap, as global emissions look likely to flatline this decade rather than showing the sharp cuts necessary to be on the 1.5°C trajectory the pact calls for. There is a gap between long-term net zero goals, and plans to deliver emissions reductions this decade.

2. The door is open for more cuts in the near-future

The final text of the Glasgow Pact notes that the current national climate plans, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) in the jargon, are far from what is needed for 1.5°C. It also asks that countries return next year with updated plans.

According to the Paris Agreement, new climate plans should be prepared every five years. That is why Glasgow was five years after Paris, with a delay due COVID, was such a significant meeting. New climate plans next year, instead of waiting another five years, can keep 1.5°C on life support for another 12 months, and gives campaigners another year to shift government climate policy. You can also request additional NDC updates starting in 2022 to help increase ambition for this decade.

The Glasgow Climate Pact also stipulates that unabated coal use should be reduced, and that subsidies for fossil fuels should be reduced. The wording is weaker than the initial proposals, with the final text calling for only a “phase down” and not a “phase out” of coal, due to a last-second intervention by India, and of “inefficient” subsidies. However, this is the first mention of fossil fuels in a UN Climate Talks declaration.

This language has been removed from the Saudi Arabian and other countries’ pasts. This is a significant shift that acknowledges the urgent need to reduce the use of coal and other fossil fuels to address the climate crisis. The taboo surrounding the end of fossil fuels is now broken.

3. The history of historical responsibility is still being ignored by rich countries

Developing countries have been calling for funding to pay for “loss and damage”, such as the costs of the impacts of cyclones and sea level rise. Climate-vulnerable and small island states claim that the historical emissions by major polluters have caused these effects and that funding is required.

Developed countries led by the US and EU, have resisted taking any liability for these loss and damages, and vetoed the creation of a new “Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility”, a way of supporting vulnerable nations, despite it being called for by most countries.

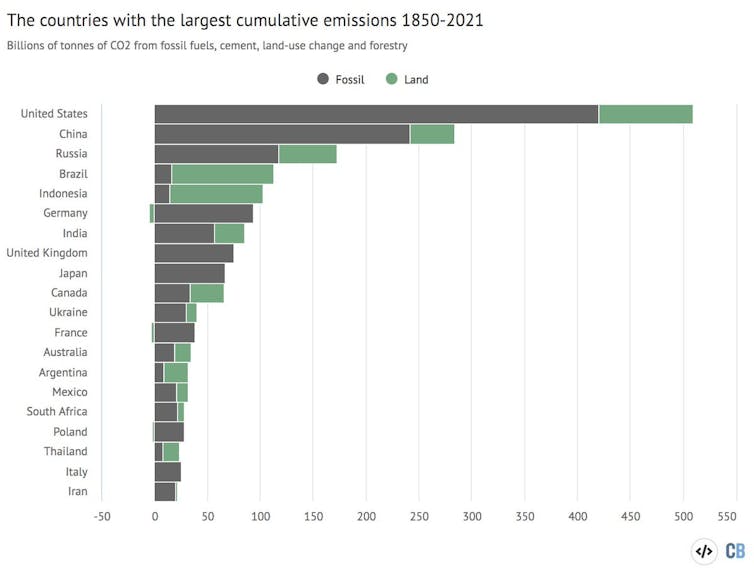

CarbonBrief, CC BY-NC-SA

4. Loopholes in the carbon market rules could hinder progress

Carbon markets could throw a potential lifeline to the fossil fuel industry, allowing them to claim “carbon offsets” and carry on business as (nearly) usual. Six years after the Paris Agreement, article 6 on market and nonmarket approaches to trading carbon was finally reached. Although the worst and most significant loopholes have been closed, there is still room for countries and companies. game the system.

Outside of the COP process we will need to have clearer and more stringent rules company carbon offsets. Otherwise expect a series of exposé from non-governmental organisatios and the media into carbon offsetting under this new regime, when new attempts will emerge to try and close these remaining loopholes.

5. Thank climate activists for the progress – their next moves will be decisive

It is obvious that powerful countries are moving too slowly. They have taken a political decision not to support a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions or funding to assist income-poor nations to adapt to climate change and move beyond the fossil fuel age.

But they are being pushed by their communities, and climate campaigners in particular. We witnessed huge protests in Glasgow, with both the Saturday Global Day of Action and Friday Fridays for Future march attracting far more than expected.

This means that the next steps for campaigners and the climate movement are crucial. This will be done in the UK to stop the government from granting a licence for the new to be exploited. Cambo oil fieldThe north coast of Scotland

As activists attempt to reduce emissions by starving the capital industry, expect more action on financing fossil fuel projects. Without these movements pushing countries and companies, including at COP27 in Egypt, we won’t curb climate change and protect our precious planet.

[ad_2]