[ad_1]

The industrialization of agriculture in the last century boosted production around the world – but that success also made our food systems much more vulnerable to the growing climate crisis.

Modern agriculture is dependent on monocrops that produce high yields and require lots of fertilizers, chemicals, irrigation, and other support.

But why is this important?

Because of the richer genetic diversity of food, as we had in the past. This will make our crops more resilient against higher temperatures and changing rainfall patterns.

Like an investor with stocks, savings and real estate, diversity in the field spreads the risk: so if an early season drought wipes out one crop, there will be others which mature later or are naturally more drought tolerant, so farmers aren’t left with nothing.

Here are five key graphics taken from our recent survey. Special reportThe fragility of our modern food system

1

There were once hundreds of varieties of corn.

Corn, or maize, is now grown in greater quantities than any other crop in history. It is still the staple food of about 1.2 billion people in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Its ability to adapt to changing climates, altitudes, day lengths and temperatures has allowed it to spread throughout the world. People enjoyed purple, black, and orange varieties, each with a unique taste.

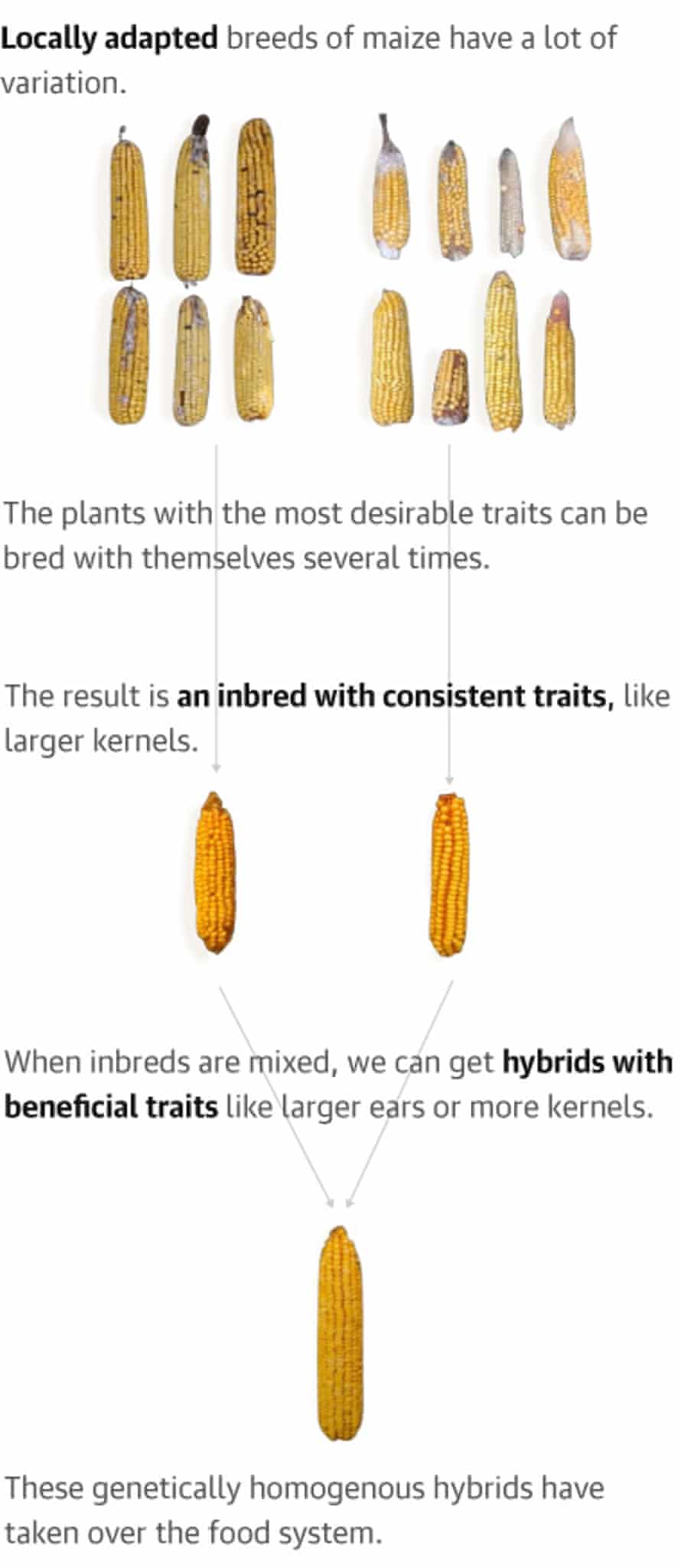

Scientists discovered in the 20th Century that they could take a locally adapted corn variety, called landraces, and self-pollinate it to create a genetically identical hybrid. And if they did this several times its characteristics would change – perhaps the plant would be taller or have a big ear of corn.

These inbreds were then cross-bred again to create hybrids.

Although hybrid seeds are required to be replaced every year by farmers, they have led to a significant increase in yield, but also to the loss of genetic diversity and other qualities like taste, nutrition, and climate adaptability. Mexico lost 80% its varieties in a matter of seconds, and today, 99% of the corn grown in the US is hybrid seeds.

2

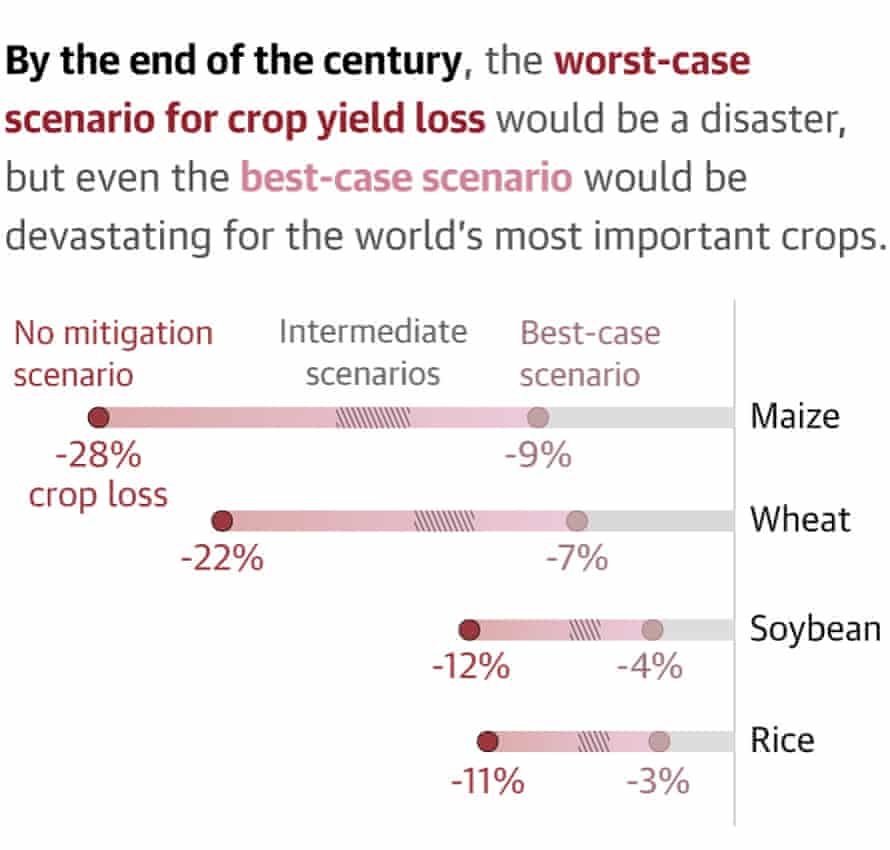

Already, climate-related losses in food production are causing significant damage to the industry.

The threat to food from climate crisis is not just a fear, it’s happening now. In Asia, rice fields are being flooded with saltwater; cyclones have wiped out vanilla crops in Madagascar; in Central America higher temperatures ripen coffee too quickly; drought in sub–Saharan Africa is withering chickpea crops; and rising ocean acidity is killing oysters and scallops in American waters.

3

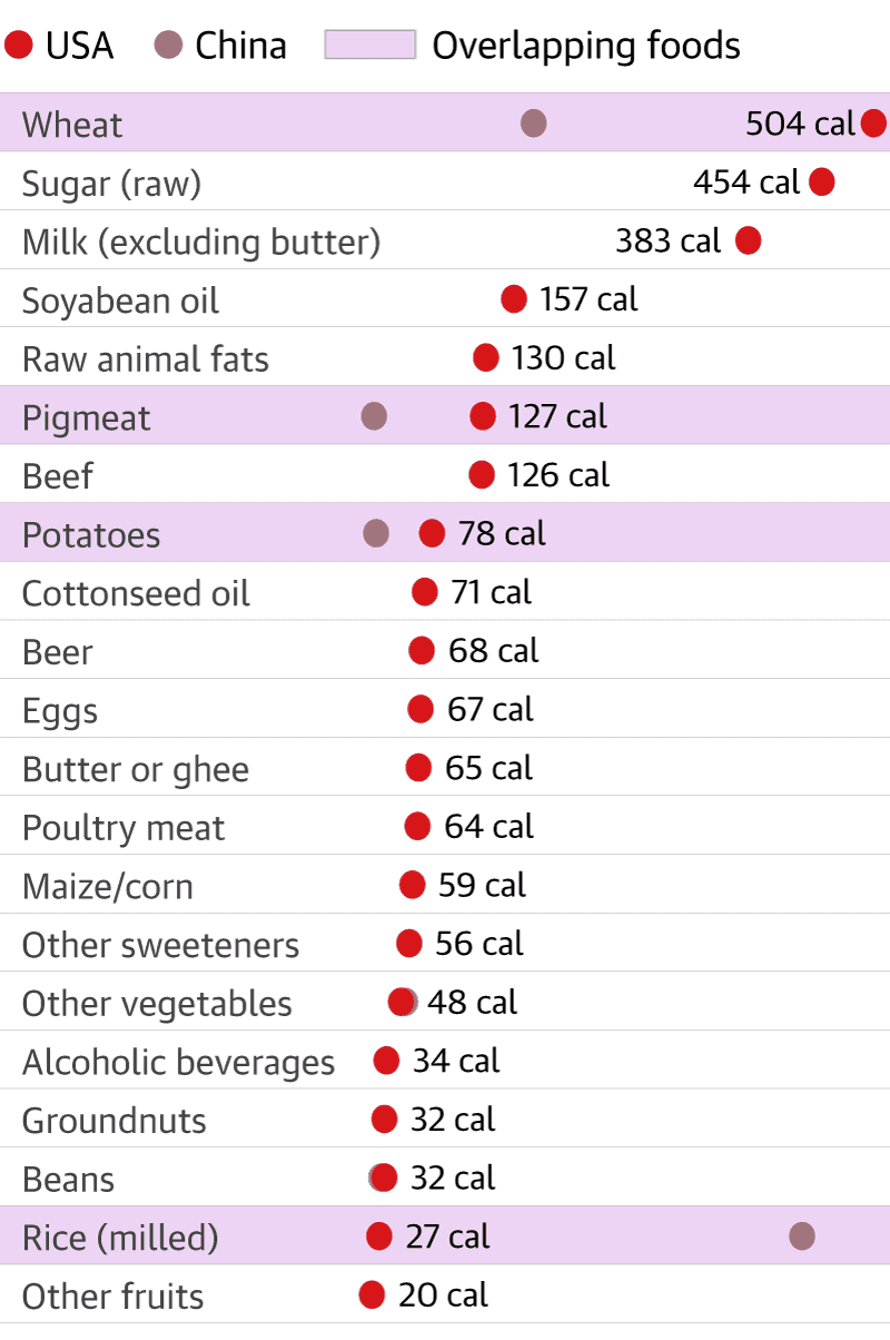

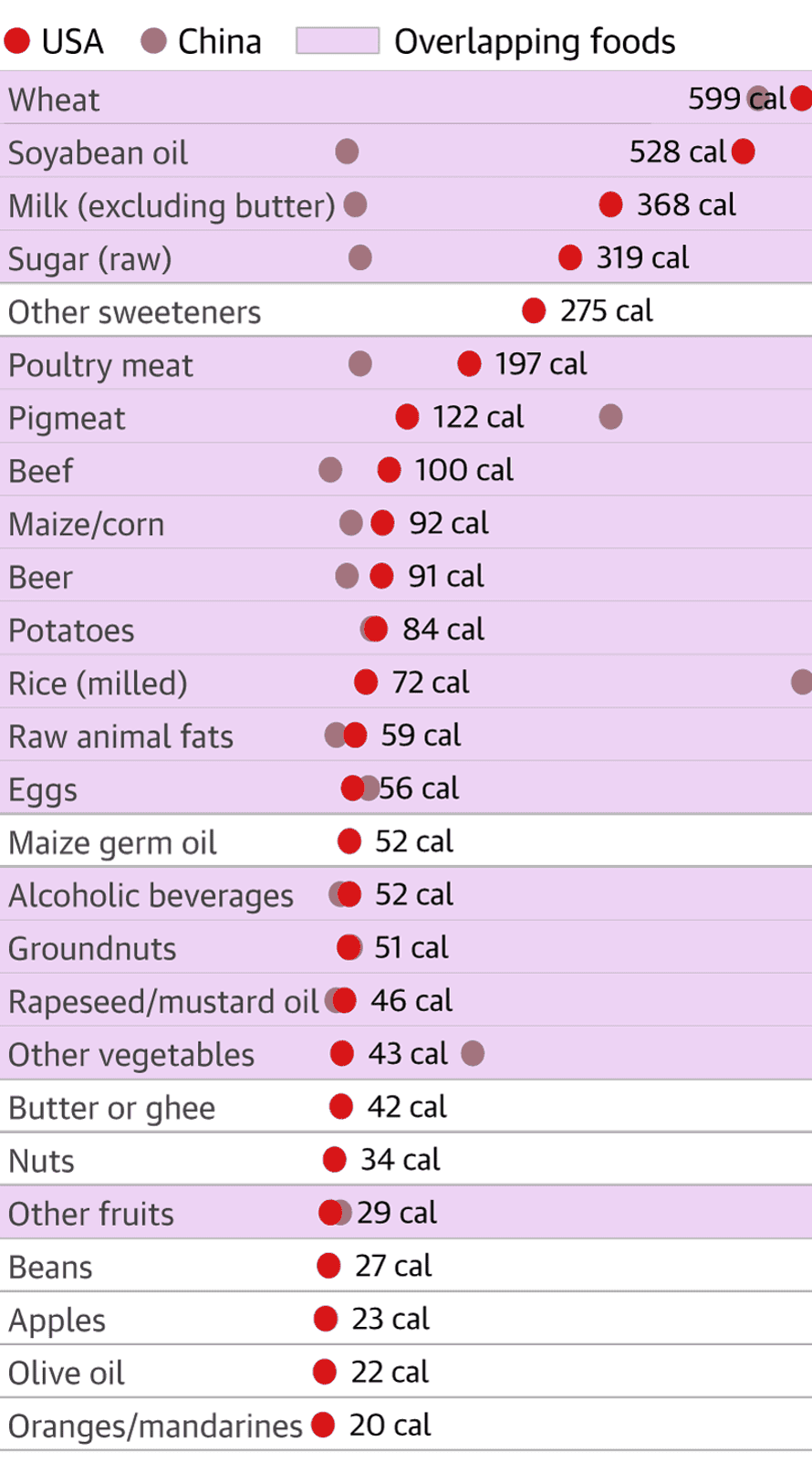

Different countries had their own diets. They now overlap

This is how many calories Americans consumed daily from different food items between 1961 and 1961.

People in China, however, ate the same foods. But the overlap between the two countries’ diets was small.

However, 40 years ago, another thing began: our diets started to overlap from country to country.

This list grew over the next half-century. People started to eat a wider variety of foods around the globe.

4

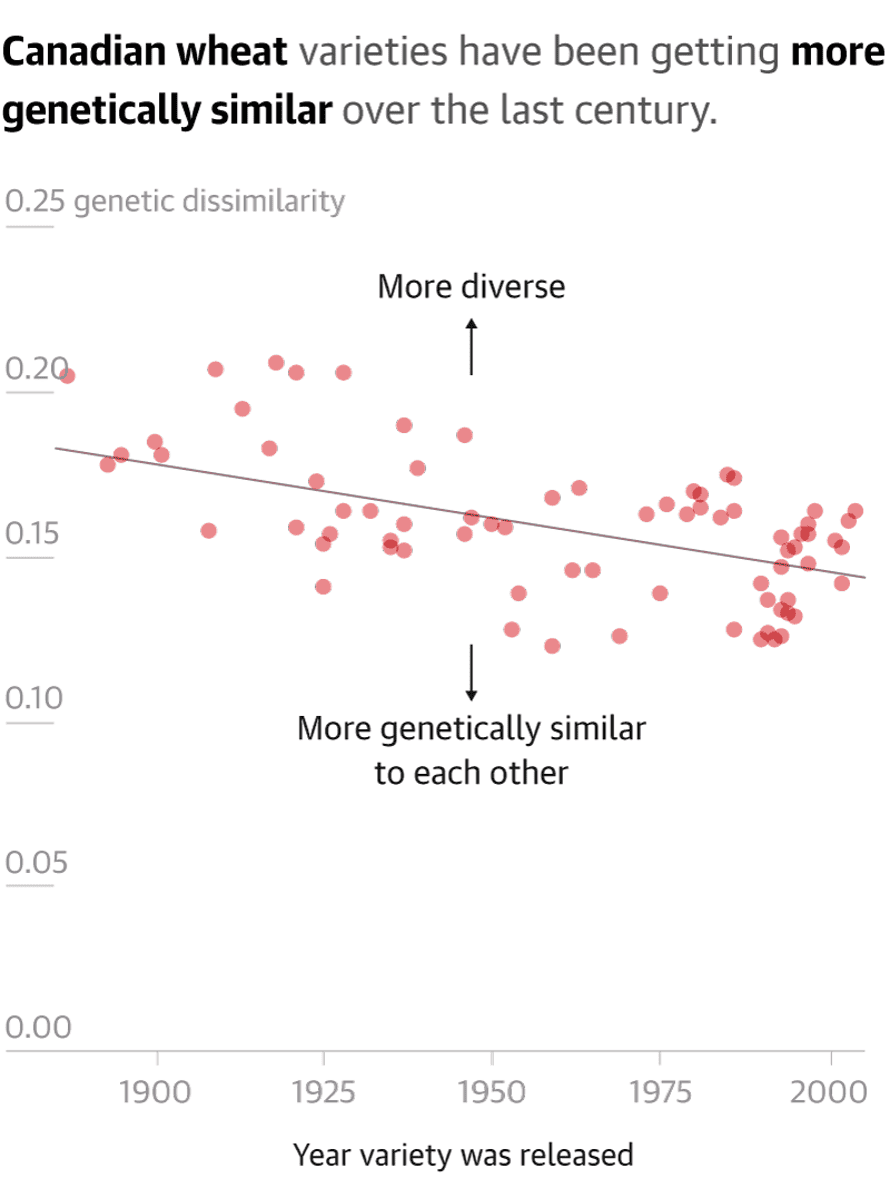

Uniformity now rules – reducing resilience

Let’s take wheat, the world’s most widely consumed grain which is grown in every continent (apart from the Antarctic) to make bread, chapattis, pasta, noodles, pizza and biscuits.

It feeds billions, but it is vulnerable due to climate change. Last year, prices for durum (pasta-) wheat were around $17 billion The rise in sales was 90% after widespread drought and unprecedented heatwaves in Canada, one of the world’s biggest grain producers, followed a few months later by record rainfall. Canadian farmers have relied more on high-yielding varieties of genetically identical wheat varieties over the past century, removing crucial diversity.

5

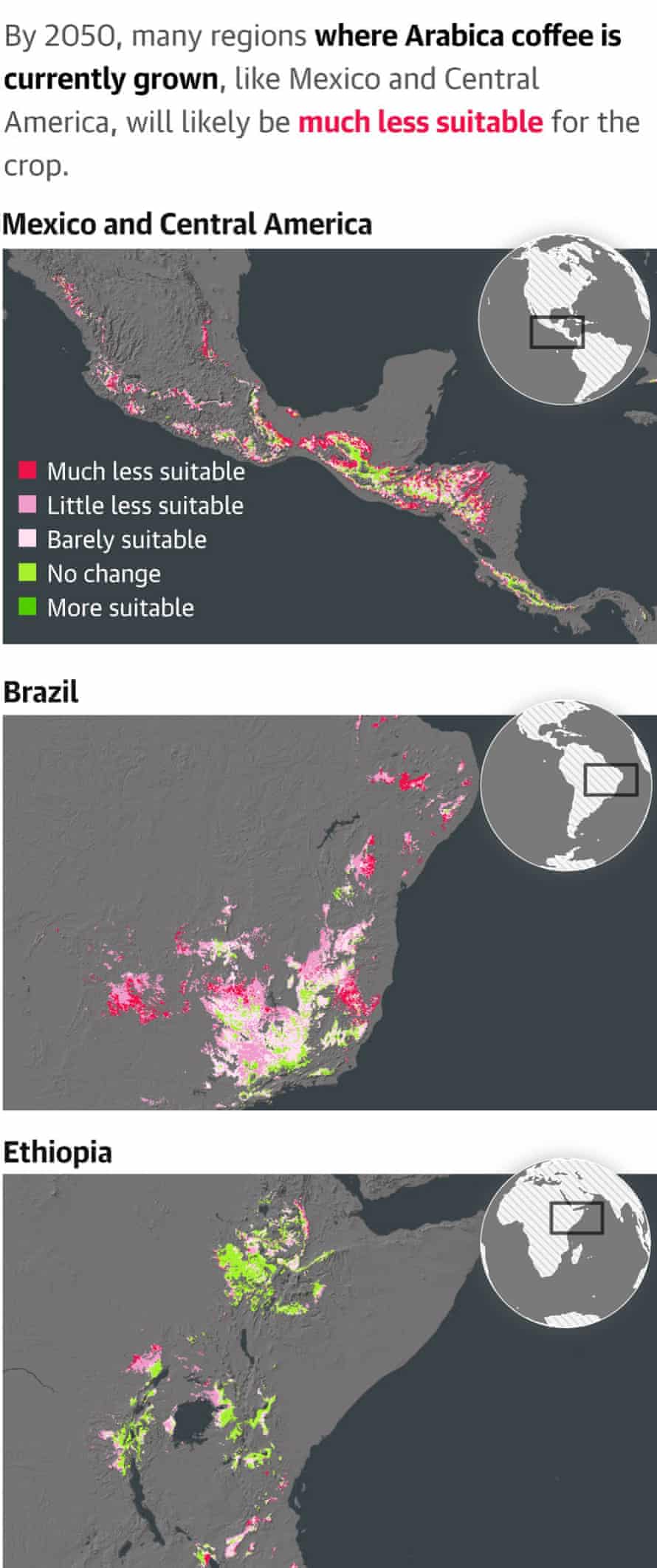

Hurricanes and drought are threatening our favorite coffee

Then there’s one of the world’s favorite stimulants. Our coffee is only two species: robusta and arabica. About two-thirds of the world’s coffee is made from high quality arabica, which is smooth and delicious. However, it is struggling to adapt to changing climate conditions. Robusta, which has higher caffeine and yields, is bitterer and more flavorful.

Wild arabica coffee is a native of the forested mountains in Ethiopia and South Sudan. However, the origins of the coffee we enjoy in our lattes or flat whites can be traced back only to two sets of arabica plant that were smuggled out of Yemen in 17th century.

Its future hangs in the balance.

Arabica can grow at 1,300 to 2,200 meters (4,200 to 6,500 feet) above sea level. It is very particular about temperature, rainfall, and humidity. When it’s too hot and dry, coffee ripens too quickly which diminishes yield and quality. Our arabica doesn’t like it to be too wet or too windy either – which is a major problem for coffee growing regions prone to hurricanes such as the Caribbean, Hawaii and Vietnam.

The climate is rapidly changing, with higher temperatures, erratic rain and more aggressive pathogens making arabica growing areas unsuitable for 50% by 2050.

6

The race to save genetic diversity – all is not lost

As the clock ticks, private sector biotech solutions are being developed. These include gene editing and genetic transgenics. They rely on genetic resources found in publicly funded gene bank and naturally occurring biodiversity to provide the raw materials. The global seed market is 60% controlled by four agrochemical corporations, and 75% of pesticides. These companies have a direct interest in making farmers dependent on their products.

It’s not all lost.

The Green Revolution was responsible for the loss of genetic diversity and prompted a global effort to conserve it.

In the end, though, we need to see greater diversity in farmers’ fields, where old varieties can once again be part of the evolutionary story.

-

This article is part a series called SeriesMore coverage will follow in the coming days about the diversity crisis in food.