[ad_1]

TAs Sofia Olsson places a chunk of wood in the fire, she raises the kettle and offers cups of tea and coffee to the small group of people seated on reindeer skins. In the taiga forest and frozen marsh outside their snow-covered Swedish military tent, it’s -12C (10.4F). Last night, it was close to -20C (-4F). But inside, it’s surprisingly comfortable.

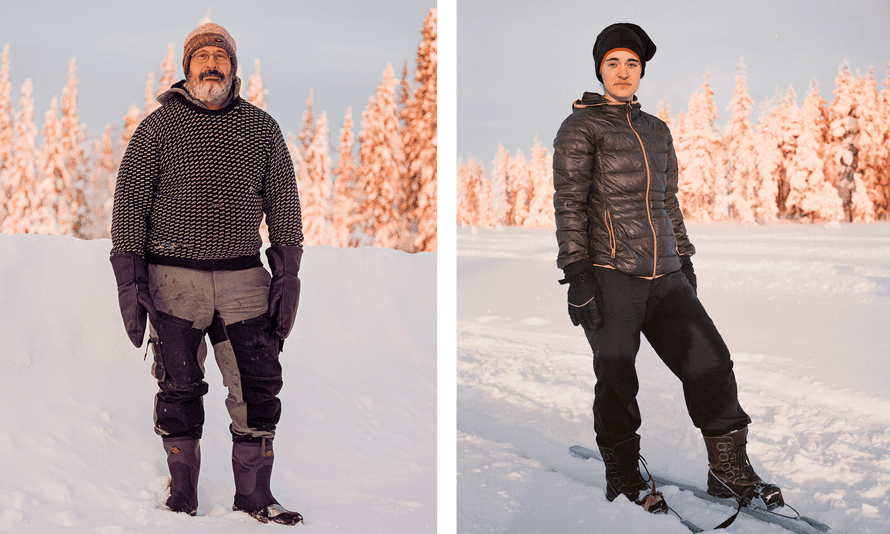

Olsson and her fellow activists Jakob Bowers and Lan Pham have been here in the hamlet of Hukanmaa, in Pajala, Sweden’s most northerly municipality, on and off for more than a year, camping since December. The camp is a post of the Swedish Red Cross. Forest Rebellion, an off-shoot of Swedish Extinction Rebellion, which says it is organising a campaign of “peaceful civil disobedience” with the Sami people against Arctic deforestation.

Leading environmental activists have begun to congregate at Swedish Sapmi, their ancestral homeland of the Sami, where they can share their knowledge and experience. The area stretches across parts of Finland Norway Russia. The German ecologist and author Carola Rackete – who made headlines in 2019 when she was arrested for captaining a ship that landed refugees on Lampedusa, Italy, without authorisation after a 17-day standoff – has arrived from her home in Norway.

The Greenpeace activist, Greenpeace, skis for 15 minutes across the frozen marsh. Dima LitvinovA protest base has been also established by Litvinov. Litvinov was one of the “Arctic 30” who came to global fame in 2013 after being seized at gunpoint by Russian special forces and jailed for trying to halt Russian oil drilling in the Arctic.

Greta Thunberg has been up to the region, too, to oppose a planned iron ore mine at Gállok near the town of Jokkmokk. Sweden granted the disputed mine qualification ApprovalThunberg criticized the decision in March, claiming that it will allow sustainable steel production and cut carbon emissions. “racist” and “colonial”Because of its disregard for reindeer migration patterns, and the potential impact it would have upon Sami communities. On Twitter, she accused Sweden of “waging a war on nature”.

Defending the land rights of the Sami – semi-nomadic reindeer herders who are the EU’s only remaining Indigenous people – is fast becoming one of the big campaigning issues for activists across Europe, bringing together climate protesters in the Nordic states with veterans of ongoing German coal protestsThe Mediterranean refugee crises.

The Sami rights issue overlaps in the fight against climate action, but it also threatens a wedge between those green activists who believe green industry could provide some of those solutions and those who are afraid it will come at cost of the environment. ArcticEnvironment and the Sami who are dependent on it.

The number of international activists here is tiny for now, but as the battle to stop the Gállok mine and other green mega-industrial projects begin to be realised, Litvinov and Rackete expect many more will join the Arctic struggle.

This morning, the discussion is focused around the campfire on future strategy. Protests are focused on the Swedish Sapmi logging industry. The group has recently achieved success in stopping the Swedish state-owned forestry company Sveaskog’s timber harvesting machine.

However, nobody is celebrating yet. “There was some excitement that by putting up this relatively small camp for a day, we forced a reaction at the Sveaskog headquarters,” says Rackete. “But the forestry industry is not going to change its behaviour overnight.”

Right:Carola Rackete was the star of the story when she was arrested in Italy for helping refugees fleeing the Mediterranean. She skied from the Greenpeace house up to the Forest Rebellion camp.Photograph by Julian Lass/The Guardian

The agreement is reached that the company will stay put for a month in order to verify its authenticity and to host training camps for activists to prepare for the Arctic battles. “We want to give them experience of skiing, snowshoeing and living up here,” Rackete says, “because I really think you will see many more actions up here in the coming years.”

But Rackete, Litvinov and the others are convinced that to truly defend the Sami way of life, they will need to embrace what seems like a paradox and oppose renewable energy projects, including Arctic wind parks, “green steel” and other parts of the so-called Green transitionIt is intended to assist Europe in fulfilling its global climate commitments.

“If we have ambitions to really change things, to enable reindeer herding and Sami life to keep going, we’re going to have to mobilise against all sorts of extraction projects,” says Bowers. This, he adds, should include the “Green transformation” of Sweden’s far-north, with its industry-leading plans for Coal-free Steel, its almost-completed electric car battery gigafactoryIt all depends on the huge wind power projects required to power it.

The green industrial transformation of northern Sweden is central to the nation’s claims to become a climate world leader. In her November, the inauguration speech, the prime minister, Magdalena Andersson, hailed the “ramping up of a green industrial revolution”, with “CO2-free steel production, battery factories … tens of thousands of new jobs” and 700bn kronor (£57bn) invested in green industry in Sweden’s Arctic north. “Sweden must show the outside world how the climate transition creates jobs and growth,” she said.

It’s easy to become enthused by the supposed climate benefits. The state company LKAB’s plans to produce hydrogen-reduced iron instead of iron ore pellets for example, promises to cut a Switzerland-sized chunk from Europe’s total carbon emissions by allowing steel plants to close their blast furnaces.

“All of this is like some sort of promise for the future, but it’s destroying what we actually have right now,” Bowers says. “We know that the Sami people have been able to live with their environment. But with these green projects, there’s no proof that it’s actually going to reduce emissions.”

Bowers reverts to an argument you might expect from a proponent of fossil fuels. “If you look at wind power, studies have shown an increase in emissions, because of all the mining and transport infrastructure.”

FHenrik Andersson is a Sami reindeer farmer who sees green industrial projects as worse than the. Malmberget iron mineThe mine, which was founded on Sami summer herding ground in 1735, and then, after a railroad link was built in 1888 became one of the largest in the world.

Andersson, from the Gällivare reindeer herding district, contacted Extinction RebellionTwo years ago, he brought activists up from Sweden and spoke with them throughout the night in his isolated cabin. (And surprised the vegans by serving them reindeer stewed and blood sausage).

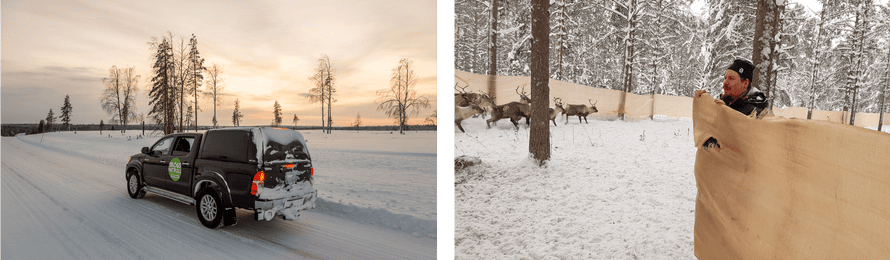

Andersson and his community are at the forefront of the climate crisis. Sapmi recorded a Temperature Last July, it was 33.6C (92.5F),More than a century. Yet, at a reindeer corral outside – one could almost say inside – the city of Luleå, it’s also evident how some of the “green” infrastructure projects that are intended as solutions to climate breakdown are also making the herding lifestyle harder by taking away grazing land.

This year’s weather has led him and his neighbouring herders graze their deer at the most southerly points of their territories: the icebound islands just outside the city. Today’s corral is taking place right by the airport, a short drive from the city’s main retail park. “Because of industrialisation and deforestation, we have no other land to go to,” he says as we drive to inspect the deer. “So we need to take this last part, that is close to the big cities.” The decision has paid off. “Really nice reindeer, healthy and fat,” he says approvingly as we stand in a swirling mass of deer, grunting and jangling with bells.

Right: Andersson checks reindeer at a corral on the outskirts of Luleå to see if any of his herd have become mixed up with those of the neighbouring Jåhkågasska district.Photograph by Julian Lass and Richard Orange/The Guardian

He says that three of the five areas his reindeer go to calve are at risk from planned wind park development. “The reindeer will for sure not stay there when they have their calves, because that is when they are most afraid,” he says, citing a Study at a Swedish agricultural university. It was discovered that wind turbines are 5km away from the reindeer. He claims that they mistake the shadows of the blades as passing eagles.

“This is land where my family have been since the iron age, and now, a windfarm with a life of about 25 to 30 years can force me from land where my ancestor put a name to all the mountains, to every river, and every creek.”

“Industry is industry, whether it’s green or not. It’s the same,” he tells me, once he has finished scanning the markings on the deers’ ears to ascertain that none are his. “The ordinary industry took some land, but the green industry wants to take even more, and we have no more land to spare. We have already passed the limit.”

Sweden’s green steel projects, he says, will need to be fed by new iron ore mines, such as Gállok ; all the so-called green industrial projects will require a massive increase in production of renewable electricity, meaning ever more wind turbines.

Märta Stenevi, one of the two leaders of Sweden’s Green party, acknowledges Sweden’s “shameful history of structural racism and discrimination of the Sami people”, but she believes a new “consultation law for issues which affect the Sami people”, which her party campaigned for and which came into force this March, can help solve the problem.

“Sweden’s green transition can take place together with the Sami and not at their expense,” she says. “It has to be done in close dialogue with the Sami so that locations can be found where it has the absolute least impact on nature, on the environment and on the Sami way of life.”

As the short spring day comes to an end, the young herders take a break to cook salted suovas – reindeer meat – over a fire and chatter about their night out in Luleå.

When I relay Stenevi’s thoughts to Henrik Andersson, he snorts. “Wherever you put windmills, we lose grazing land, so whatever they say, there cannot be any cooperation. There can maybe be small parks on the edge of a mine or far out to sea, but not these big machines, that is impossible.”

Andersson believes that the new law does nothing to give the Sami any veto rights. “We need to have a veto,” he says. “To be able to say no.”

The Forest Rebellion activists set up their tent just 15 minutes away from the ski lift. GreenpeaceThe campaigners’ relationship with house is not ideal, even though they share a common concern for the Sami. The charismatic Litvinov, with his stream of enthralling war stories from 33 years with Greenpeace, calls the Forest Rebellion group “the anarchists”, ridiculing them for their endless meetings, obsession with consensus and supposed lack of any clear strategy.

They seem wary of being dragged into his orbit. “You don’t like me!” he says in mock exasperation, throwing his hands in the air, when asking them why they don’t come to the house more. “No Dima,” Olsson shoots back. “You don’t like us.” Even so, a few days later, Litvinov hands the house over to the activists.

They all agree that “green industry” is a contradiction in terms. “They want us to believe that the same industry that put us into the environmental crisis is going to get us out of it,” Litvinov says, as we watch the reindeer herders.

“As long as we’re continuing to be stuck in a system of continuous growth and continuous economic extraction of resources, we’re still going to be going down.”