[ad_1]

Believe it or not, it’s nearly 2022 and some people still think we shouldn’t do anything about the climate crisis. Despite the fact that most Americans know carbon emissions are heating the planet and want to do something about it, there are increasing attacks on clean energy and policies that limit carbon emissions.

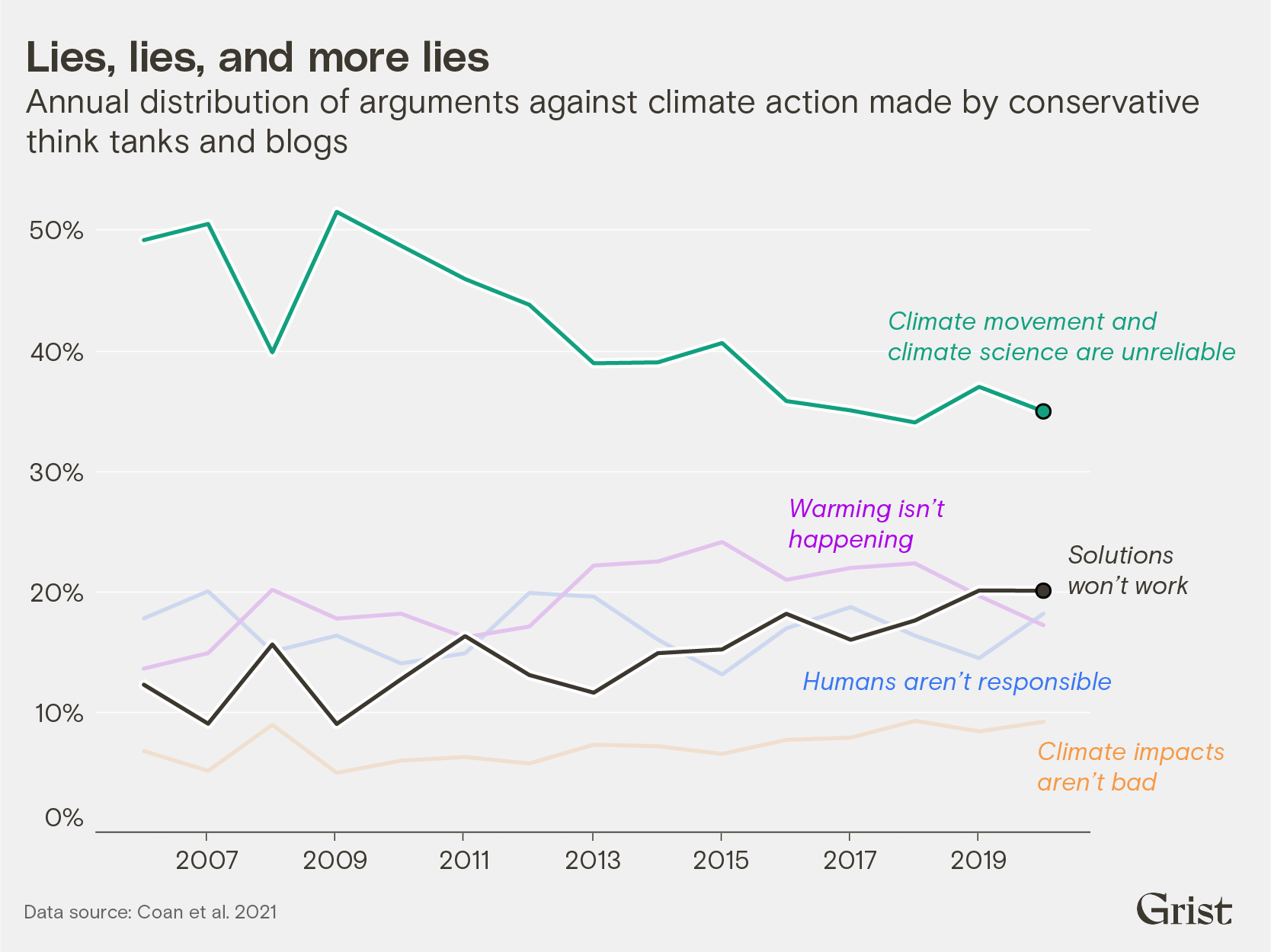

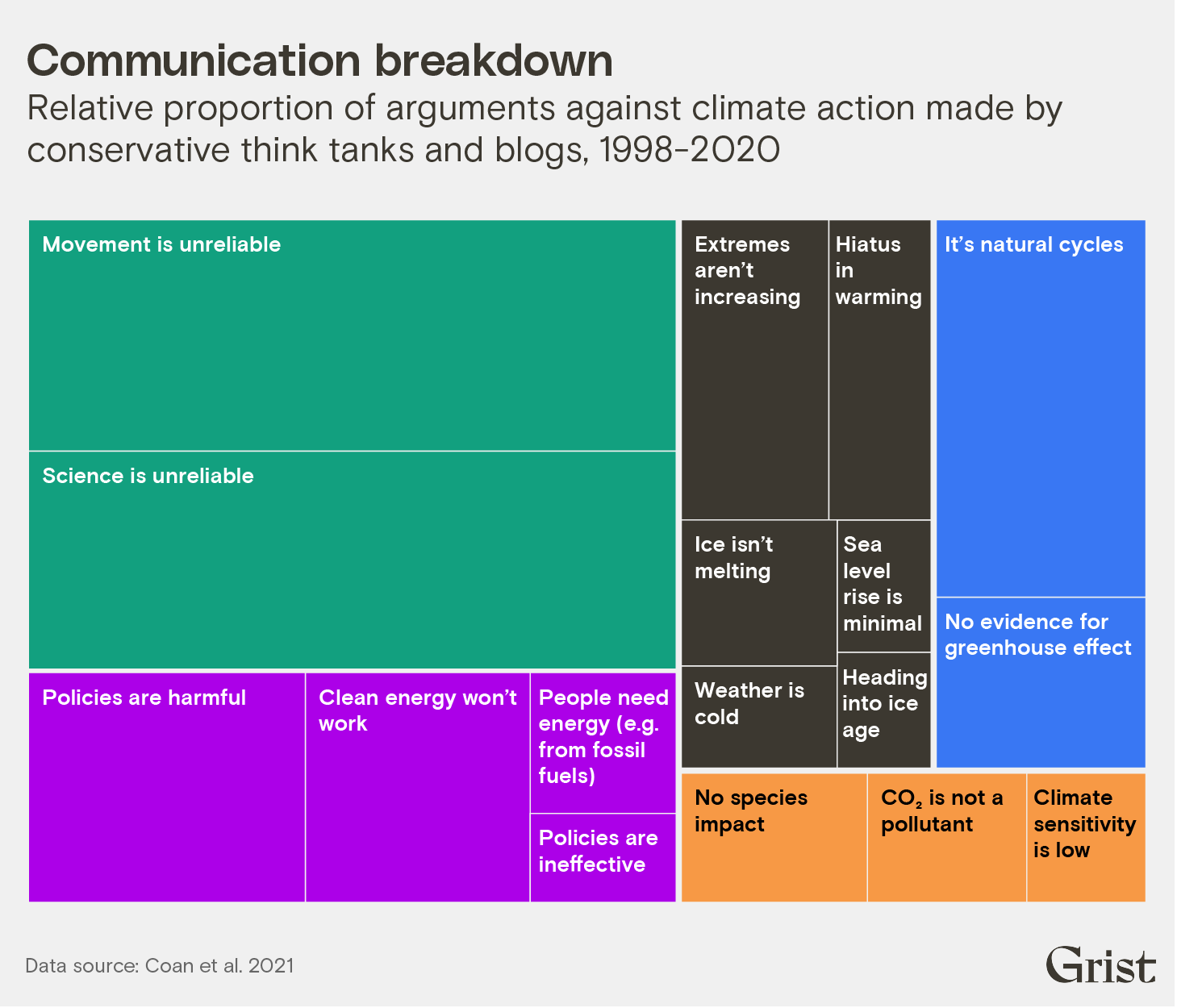

In a studyResearchers discovered this week in Nature Scientific Reports that denying science is becoming less fashionable. Today, only 10% of arguments from conservative think tank in North America challenge the scientific consensus on global warming or question data models. (For the record, 99.9 percentMost scientists agree that human activities are heating up the planet. Instead, the most common arguments are that scientists and climate advocates simply can’t be trusted, and that proposed solutions won’t work.

This was a surprise to researchers. Scientists get called “alarmists,” despite a history of underestimating the effectsThe planet is heating up. Politicians and the media are portrayed as biased, while environmentalists are painted as part of a “hysterical” climate “cult.”

“It kind of dismayed me, because I spent my career debunking the first three categories — ‘it’s not real, it’s not us, it’s not bad’ — and those were the lowest categories of misinformation,” said John Cook, a co-author of the study and a research fellow at the Climate Change Communication Research Hub at Monash University in Australia. “Instead, what they were doing was trying to undermine trust in climate science and attack the actual climate movement. And there’s not much research into how to counter that or understand it.”

Researchers found that attacks on “climate solutions” are also on the rise. People who want to delay action often argue that renewable energy can’t replace fossil fuels. They also claim that climate policies will harm working families, ruin the economy, raise prices, and cause more pollution. These arguments tend to overlook the impact of fossil fuels on pollution. shortens lifespans and how climate-charged disasters like wildfires, flooding, and heat waves are already ruining people’s lives and costing billions. They tend to overlook the potential economic consequences of a changing climate for the U.S. 10.5 percent of GDPBy the end the century.

“Climate solutions misinformation is really the future of climate misinformation,” Cook said. It has been the predominant argument from conservative think tanks since 2008 and recently became the second-most common point made on anti-climate blogs, beating out the increasingly unbelievable claim that the Earth isn’t warming.

Researchers from Australia, Ireland and the United Kingdom used machine-learning to classify arguments against taking action on climate change. They also tracked their evolution over time. They analyzed over 255,000 documents between 1998 and 2020, mainly from the United States, using material from 33 popular blogs and 20 think tank websites.

Cook and his team took five years to develop a machine learning model that could accurately detect climate misinformation claims. “Misinformation is messy and doing content analysis is messy, because the real world is always a bit blurry,” Cook said. First, they developed a taxonomy to sort arguments into broad categories — say, “climate change isn’t bad” — narrower claims (“carbon dioxide is not a pollutant”) and even more specific points (“CO2 is food for plants!”). They then fed common climate myths to the machine until it could recognize them all in the wild.

The study also tracked the evolution of arguments against action over time. The study showed that misinformation regarding solutions grew before international climate conferences and at times when Congress was considering climate legislation, such the American Clean Energy and Security Act. Conservative think tanks claim that the policy will have a negative impact on the economy after the announcement of a large climate bill. Then, there will be another spike just before the bill goes to the vote.

That means there’s also “an air of predictability” around misinformation, Cook says. “If we’re proactive enough, we can get ahead of it and inoculate the public,” he said.

Last year, Cook released a free game that “vaccinates” people against fake news. A cartoon character called Cranky Uncle — representing conspiracy-prone uncles everywhere — uses his favorite techniques to teach you to become a science denier like him. Learn how to CreateFake news teaches people how to spot logical errors and other techniques used for dismissing scientific evidence, such as cherry-picking temperature data or citing fake scientists. This approach, called “pre-bunking,” has been shown to be effective — playing a similar kind of game can reduce people’s susceptibility to misinformation for three months, one study found.

Cook believes Cranky Uncle games could be used to counter climate change arguments or attacks on the movement. “Pre-bunking is kind of a universal template,” he said.

[ad_2]