TWitnesses claim that the apocalyptic feeling caused by the hundreds of bushfires that erupted in southern Australia on February 7, 2009 was apocalyptic. It was already scorching hot in Melbourne that day, at 46.4C. As the fires erupted into flames, day turned into night, flaming matches the size of pillows fell down, and birds fell from the trees. The ash-filled air became so hot that one survivor described it as like sucking on a hairdryer. 173 people were killed and more than 2,000 homes were destroyed. The New South Wales fire chief visited Melbourne days later and encountered shocked, demoralized firefighters, feeling powerless.

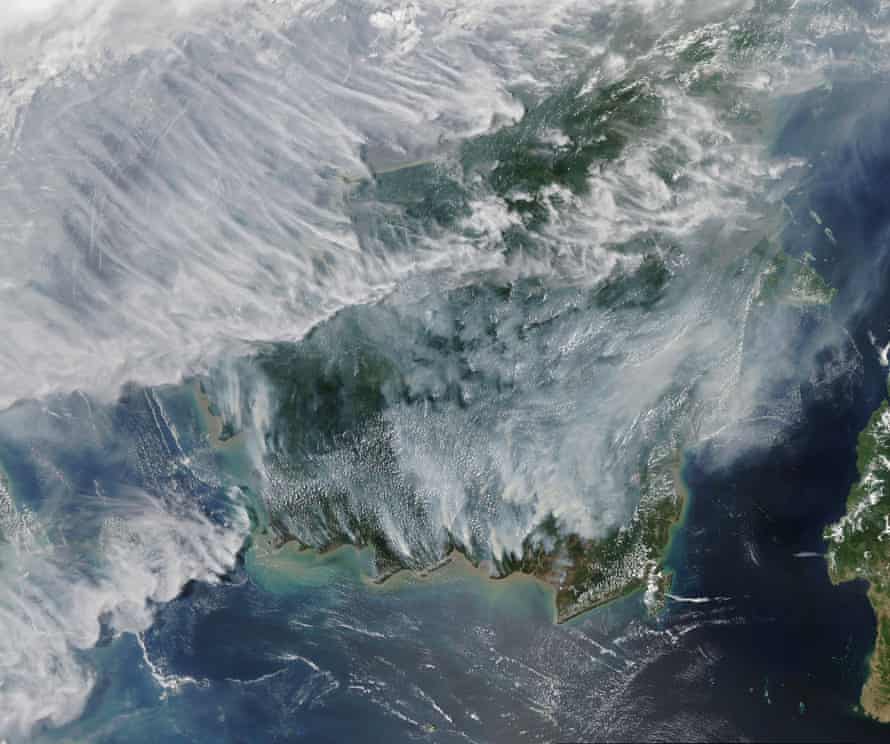

Australians consider the event Black Saturday a scorched pit in the national calendar. It competes with Red Tuesday and Ash Wednesday, Black Thursday, Black Friday, Black Friday, Black Sunday, and Black Sunday on Australia’s calendar of conflagration. It has been overtaken by the Black Summer, the ferocious 2019-20 fire season that claimed hundreds of lives and burned an entire area the size Ireland. The bushfires killed or displaced 3 billion animals, according to a study. Its stunned lead author couldn’t recall any other fire that had caused this much death.

This will continue. As the planet heats, combustible terrains will dry out and ignite. Greenland, which is less fire-prone, will also catch fire. Environmentalists should now Please contact us to imagineThe whole world is on fire. Our new picture of climate collapse is a wildfire. Its message is simple: The more we crank up heat, the more everything will go. This is the thermostat model. The headlines are reporting massive fires. SacramentoTo SiberiaIt’s easy to feel as though we are at the edge of a catastrophic global conflagration.

The truth is, however, stranger. Satellites enable researchers to monitor wildfires all over the globe. When they do, they don’t see a planet igniting. Instead, they see one in which fires are extinguishing quickly. Although fire has had a long and productive history in human history, there are many other uses for it. It is now less commonThere is more fire around than any time since antiquity. We have been removing fire from the landscape and from our daily lives where it was once a constant presence. The once harmonious relationship between fire and humanity has turned hostile.

Today, there are fewer fires than ever before, but the ones that remain are still quite formidable. Our pyroscape is becoming increasingly chaotic, with fire taking on new forms, visiting new places, and using new fuels. These results are as confusing as they are disturbing, and our instincts are not good guides. While we hear a lot about fires in areas where wealthy people live, such as Australia’s south or the US west, fires tend to be more deadly in areas where poor people live, such as south-east Asia or sub-Saharan Africa. The most deadly fires are not the most dramatic and spectacular, but the smaller, more regular ones that are seldom reported by global media. They are more likely to die from smoke than fire, and their main cause isn’t global warming. Many are fueled by corporate-driven land clearing.

These conclusions are not comforting. These conclusions suggest that fire is much more complex than the thermostat model. It is affected by how we grow and place our settlements. It also depends on how we fuel our cars. It will take more than just managing the rising temperatures, which is still vital to solving our fire problem. It will also require us confronting a longer history, which, since the Industrial Revolution has thrown our relationship to fire out of control.

Rapid economic growth has lit fire in old places and brought it to new places. The climate crisis has further unbalanced the system. Unpredictable fires are a complicated result of ecology and economy. They’re not ones we’ve prepared for.

HWilliam Martin Joel, a noted pyrohistorian, stated that humans didn’t light the fire. Has argued. It was always there, ever since the worlds were turning. We now know that the Joel Hypothesis may not be entirely correct. This is because fire wasn’t invented by people. Surprisingly, it is a relatively recent phenomenon. The planet was unburnable for about nine-tenths Earth’s history, which lasted around 4bn year.

To ignite fire, you need fuel, oxygen, and a spark. Although lightning, volcanoes, and even tumble rocks can spark fire, there is no oxygen or vegetation that can supply it. Only after cyanobacteria had filled the atmosphere with oxygen and mosses, and spread stemmed plants over land, around 450m year ago, did the first fire break out.

It was not only the first fire on Earth, it was also the only fire within trillions upon trillions of miles. The sun isn’t aflame, despite its appearances. Its heat, light, and radiation come from nuclear fusion and not combustion. Scott Baird, a physicist, suggests that you should not think of the sun like a huge campfire. Instead, think of it as a gigantic hydrogen bomb. We know of no other planet that has fire, even outside of the solar systems.

Fire thrives where life thrives, and the two are dependent on each other. Pyrophilous (fire-loving), plants and animals include the following: BeetlesThey lay eggs in the burned trees Pine conesTo release their seeds, they need to be ignited. Whole ecosystems depend on fire to clear out space. A 2005 scientific study found that fire is as important as rain and sun in many habitats for the survival of plants and animals. Survey found.

The most successful pyrophilous plant is Homo sapiens. Early humans used fire for warmth, light, warmth, social gatherings, and protection against predators. Instead of spending hours chewing, fire allows us to absorb nutrients quickly by cooking. Orangutans, gorillas, and Chimpanzees all eat raw food. However, their brains are smaller. Our large, resource-intensive brains are supported by the caloric boost from cooking. Simply put: no fire, no us.

No us in an evolutionary sense. Every human society known has used fire. Our ancestors used fire to create light and heat, and also to repel pests and flush out game. They could hunt individual animals using spears; with firesticks they could alter entire landscapes.

It is easy to view our forebears as vandals who used their torches to light forest fires. But it is more accurate to consider them gardeners. Fire allowed people to domesticate spaces by opening paths, creating meadows, and beating back the wilderness. A clearing that has been burned in the woods was referred to by the ancient Romans as a LucusThe root of lucid, a sacred grove from which the light entered it, is shared by lucid. To protect themselves from wildfires, people set their surroundings ablaze to burn away any fuels that might accumulate and cause a raging blaze. Henry Lewis, an anthropologist said that fires made of choice were able to replace fires caused by chance.

How must it have felt to use fire in this way? Victor Steffensen sheds some insight in his Recent bookFire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Can Help Save Australia. It contains the following: Two brothersPoppy Musgrave and Tommy George were Aboriginal elders and the last speakers to speak the Awu Laya tongue. The stolen generations era, which lasted from the early 20th Century to the 1970s when large numbers of Aboriginal children were forced to immigrate by Australian authorities, saw the pair grow up. Musgrave and George avoided that fate by hiding in mailbags. They managed to escape capture and served, up until their deaths as key repositories for a culture that was endangered. They carried not only their language, but also firesticks.

Steffensen was told that the old people used always to burn the country. Musgrave and George believed that fire was not destructive but purifying. Musgrave and George were frustrated at the thick vegetation others may perceive as lush or plentiful. They considered the country overgrown to be sickening and deplorable. They screamed, “We need to burn it!” to make it healthy.

English arsonist is the name for someone who lights fires.. It’s quite remarkable that there isn’t a common term for someone who cares about a landscape infused with flame. Steffensens book demonstrates that this is a noble calling. The book is full of wisdom shared by the brothers, including when and how to set boxwood country ablaze so that nearby ecosystems are not destroyed, and which gum trees to burn and which ones to leave.

Australia is a notable example of firestick agriculture. It is home to Aboriginal people who used firebrands to travel with and light the brush while they walked. However, there is every reason for us to believe that the practice was worldwide. Europeans encountered people from Africa, Asia, Americas, and the Pacific in the 16th century. They reported seeing them set fire to all of these places. This shouldn’t have been surprising, as Europeans had also set fire to their own lands.

THistory of humanity is the history o fire. However, you wouldn’t know it from seeing how people live now. The return of fire, natural or human-made, has been largely hidden from our view.

Some of this fear makes sense. For centuries, cities were built largely from organic materials. Thatch and wood were common and easily combustible. London’s 1666 fire which destroyed more then 13,000 structures is famous but not unique. Six years prior, Constantinople had been leveled by a fire 20 times as large.

Eric Jones, a historian, argues that Europeans put out these fires by switching to flame-resistant materials. Jones refers to the brick frontier as it spread across Europe in 17th-18th centuries and quickly spread elsewhere. Urban blazes became rarer as brick, concrete, and eventually steel structures replaced wooden ones.

Europeans were not limited to their cities. Their inventions made it possible to light fire in everyday life. Steam technology moved from the hearth to the boiler. Electricity was a source of energy, light, and heat that worked quietly and quietly without any indication of its origins. Today’s lifestyles are dependent on combustion. More than five-sixthsThe majority of global energy comes primarily from fossil fuels. Many of us can go for weeks without lighting a fire, except for the controlled flames of a stovetop gas burner or occasional candle or cigarette.

Is that a problem or not? It may have been to the ancients who worshiped fire gods. Yet, modernity’s dominant mindset has been one of intense Pyrophobia. The Enlightenment was a society that valued illumination. The philosopher Michael Marder observed that it did this as light without heat. Western technology has eliminated flames and made firestick farming dangerously primitive.

Or, perhaps, just dangerous. European scientific forest, which developed in the 18th Century and spread all over the globe, had as its mission to extinguish fire. Only YOU can stop forest fires was the message that the US Forest Service instilled in children through its famous mascot in the 1940s. Smokey Bear. But should Forest fires that occur naturally and have been profitably started by humans for millennia should be stopped. This question was not considered serious by forestry officials until the latter part of the 20th century. They tried to put out all flames until then.

Today, forest managers are recognising cultural burning and have stopped using suppression strategies. (Poppy Musgrave, an Australian university, awarded the honorary doctorates to Tommy George and Tommy George to their elders before they died in 2006-2016. However, there is still widespread fear about fire. This is why environmentalists continue to love images of wildfires. A forest burning is nothing unusual, novel, or unnatural. Fire is a terrifying thing for us, but we are children of Enlightenment.

IThe nfernos are blazing hot on our screens. Scientists have repeatedly pointed out that the amount of land being burned each year is decreasing. By a lot. According to a study, it fell by 25% between 1998 and 2015. A 2017 studyScience. Even California, where flames are prohibited, is not spared. They have increasedIn the past 20 years, it has been markedly less fiery. Stephen Pyne, a remarkable historian of fires history, estimates fires from both natural and human-caused origins burned twice as many acres before Europeans arrived.

This is counterintuitive. The global decline in fires is not good news. Humanity is expanding, which is the main reason fires are decreasing. In the savannas of South America, Africa, and the grasslands in the Asian steppe, sprawling settlements and industrial farms serve as firebreaks. Livestock eat vegetation that could otherwise fuel large fires. The 2017 Science study found that capital-intensive agriculture has caused a decrease in fires. The decrease in fire-prone landscapes in sub-Saharan Africa, northern Australia and northern Australia is more significant than the rise in megafires that grab headlines.

It may seem as though the world has been made safer by putting out wildfires. It has made fires more dangerous. The biomass that would have normally been used for firewood instead becomes kindling. It takes decades of fire suppression to create timebombs. The supercharged blazes that do burst are more dangerous and harder to control. This is what the US currently experiences each year: The number of its fires is decreasing, while their size is increasing and the cost of fighting them is rising.

While purposeful burning can help reduce dangerous fuel loads, it can also cause damage to the landscape if it isn’t accompanied by centuries of experience. A prescribed burn was allowed in a federally-protected area of New Mexico in 2000. It was too late. More than 18,000 people were forced to flee the scene. The fire also reached the tritium facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory. (Had it burned, radioactive contaminants could have spread widely). This was the result of complex calculations. ConfessedThe secretary of the interior was seriously flawed.

They were. However, in New Mexico, a place where decades of settlement spread, fire suppression, and land loss have rendered the land without flame, even the slightest contact with industrial life or dry vegetation can result in a downed line, an exhaust pipe brushing the grass, and conflagration. The Ranch Fire, a California blaze that burned 1,660 km in 2018, was the result. How did it start? SparksA rancher strikes a stake of metal with a hammer. The resulting fire lasted 160 consecutive days.

Global heating, which dries fuels at fire-prone locations, will only make it worse. Global heating is an outcome of our modern relationship to fire. We haven’t stopped lighting things, despite the appearances. Instead, we have put out open and visible fires and reduced burning to boilers or vehicular combustion chambers. Fire feasts on fossilised plants, not living grasses or trees, but on shrubs and trees that died hundreds of thousands of years ago.

It is vast. The land’s ability to grow living vegetation and the amount of people and animals it can carry are both very limited. However, fossil fuels require us to dig into the deepest reserves of ancient organic material, which we then incinerate. Whole centuries of valueEach year, there are approximately 500,000 buried plants. The coal, oil, and gas We burnEach year, it took as much organic matter as the entire world needed to produce. It took approximately 600 years. As we burn it, we release carbon from the atmosphere that has been lying dormant for a long time.

Pyne, a fire historian, observed that this has changed the way we view time. We used to lighten the plants around us, but its effects were limited to our day. Now, we extract plant matter from deep into the past, burn it now, and send its byproducts soaring into an uncertain tomorrow.

We know that the future will be hot. The heat is extending fire seasons in the most flame-prone areas. After Black Saturday 2009, Australians updated their fire danger index, adding a new category. CatastrophicTo describe the record-breaking conditions they now frequently encounter.

The global trend is still downward, and the increased temperatures have not resulted in more fire. The increased heat, like fire suppression, is encouraging new types of unruly fires such as those in far north. The Arctic has large amounts of ancient peat vegetation that hasn’t completely broken down. Many of the peat was buried under frozen ground, or protected from flames by cold and damp conditions. As permafrost thaws and summers grow longer, rich peatlands are exposed to fire and ignite quickly. Scientists are now trying to understand the situation. zombie firesThey can survive winter by eating smouldering peat under the ground and emerge in spring with huge carbon stores.

We are now in a geologic epoch where our behavior is the main driver for the climate. It is often called the age of humanity, or the Anthropocene. Pyne Think about itWe could also call it the Pyrocene or the age of fire. It was the fire that got us here. Now, we face the consequences of Earth’s unhinged geogeography.

In Athens, Greece, you can see flames as they lick the streets. Boulder, ColoradoIt is hard to disagree. We were addicted to burning things. But we kept fire as a shameful secret, hiding from the public and storing it in boilers. Now it’s spilling out, uncontrolled: It’s the return of those who were suppressed.

TCalifornia has been the victim of eight of the 10 wildfires that ravaged its combustible landscapes. Recorded largest firesThe threat of climate collapse has been highlighted in the last five years. Despite all the attention, the California fires have been more dramatic and deadly than expected. The 2018 Ranch Fire which burned For monthsOne person was directly killed by this fire. California’s 2020 fire season was the worst in modern history. It was nearly as deadly as three days of traffic accident on California roads.

We rarely acknowledge this fact about megafires: they can kill animals and plants but not humans. The Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (Universit Catholique de Louvain) maintains a repository. DatabaseMore than 22,000 large-scale global disasters have struck the world since 1900. Its database shows that earthquakes killed an average of more than 2,500 people per year, while floods claimed nearly 11,000 lives. But what about wildfires? They killed on average 23 people, rounding up.

It’s not that fires can be harmful. It’s just that they can cause harm in ways that are not immediately obvious. Unless you’re a firefighter or a firefighter, it is very unlikely that you will die in a major blaze. You can save years by inhaling the chemicals and particulates that fires emit.

Wildfire smoke has a devastating effect on the lives of 339,000 people each year. According toFay Johnston, a public health specialist from Australia, was killed along with her colleagues. Few people die in the affluent areas known for their telegenic flames, such as North America or southern Australia. Johnston and her colleagues have compiled more than 400 deaths from Australia’s 201920 Black Summer. Have estimated). The vast majority of them die in poorer areas, where fires can be more severe, such as sub-Saharan Africa or south-east Asia.

The fires in South-east Asia are particularly alarming. They aren’t visiting land that has been regularly burning for millennia. Instead, they are feeding on Indonesian forests or peatlands that have been reintroduced by economic development. These are not thermostat fires. Global heating is the main cause of these fires (though it is not helping). They’re chainsaw fires lit when timber, palm oils, rubber, petroleum, and other gas firms open the closed-canopy rainforest. The ecosystem, which is largely fireproof, becomes combustible when moisture floats out and winds blow in. Plantation managers have made it easier by torching trees in order to clear the land. And it appears that those who were evicted from plantations may be setting fires as a retaliation.

Suharto, Indonesia’s president, started the Mega Rice Project to convert Central Kalimantan’s peatlands into Indonesia’s new rice bowl in 1996. Suharto was almost 30 years old and had managed to gather the support of tens, if not thousands, of workers. Discover 6,000km of canalsCentral Kalimantans had waterlogged peat forests. This did little to improve the area’s development. However, it exposed long-submerged peatlands with their large amounts of prehistoric carbon to the flames.

None of the fires in Indonesia over the past decades have been particularly notable. They’ve all been catastrophic. A dense cloud of particulates from Indonesia’s fires could be seen as far as Thailand and the Philippines in 1997. A commercial plane was seen landing at Sumatra’s centre of Indonesia’s fires that year. CrashAll 234 people aboard were killed due to poor visibility. 29 crew members perished when two ships collided off Malaysia’s coast.

Maria Lo Bue is an economist It was found thatThe 1997 haze saw Indonesian toddlers grow shorter, went to school six months later, and finished almost a year less than their peers. Seema Jayachandran (another economist) also contributed. FoundThe fires caused over 15,600 deaths of infants, children, and fetals, a devastating effect on the poor.

Indonesias fires keep coming back, as does its haze. Air quality issues are now a regular cause of school closures, business losses, and flight cancellations. 2015 was another poor year. The plume from Indonesia’s fires was another problem. Stretched starting atFrom east Africa to the middle Pacific. The fires that burned a lot of dried peat were also releasing unimaginable amounts of carbon previously stored in the atmosphere. The height of the 2015 fire season, Indonesia was More emissionsGreenhouse gas emissions are lower than in the US each day.

This disaster, which engulfed Indonesia, the fourth-most populous country on earth, in a choking cloud and severely exacerbating global heat, seems to be a story with legs. International coverage of Indonesia’s fires has been limited at best. You can find books about California’s wildfires in almost every angle. As firefightersInspirational chronicleA high-school football team representing a town that has been devastated by fire, childrens bookLearn more about how to escape wildfire AccountZen practitioners protecting their monastery from a fire. Amazon’s search turns up one book in English about Indonesia’s fires of the past two decades: an 80-page economists assessment on government mitigation programmes.

This unbalanced coverage results in a distorted understanding. When we think about the way humanity is setting fire to its own flames, we think global heating. This is the sum of all our energy use. The global crisis caused by our planet’s burning becomes an existential emergency, linked to modernity and not tied to any particular company, activity, or government scheme. We tend to think about how fire affects the rich, whose property is at threat, rather than the lives of the poor.

Imagine a dangerous fire. You’re likely to picture a dense forest of tall trees burning in a dry climate. However, smouldering scrub or peat that is being fueled by a tropical road can be a more accurate representation. The real threat is not catching fire, but the Slow violenceBreathing in bad air. Your father has a hacking cough and your daughter is too young to go to school.

FIrre is not necessarily a bad thing. Many landscapes that are built to burn would not exist without regular, natural or intentional fires. We now see that foresters made a grave mistake when they tried to suppress fires everywhere. We don’t have the ability to get a fireproof planet, nor should we.

It is easier to think of fire in terms of rain. Our world relies on precipitation. Some ecosystems even depend upon floods. It is possible to have too much rain in one area and not enough elsewhere. This can lead to some areas becoming dry and others becoming dangerously inundated. Similar things happened with fire: too much and too small at the same moment.

We need to have a better relationship with combustion. We need regular, restorative fires instead of erratic, uncontrolled ones. Our forebears were not afraid to light – they were constant fire-setters. Two important rules were followed by them. They used living vegetation to fuel their fires, which helps to reclaim carbon lost as it grows back. They were guided by their long-standing experience with complex fire paths and their consequences.

We have exploded far beyond both of these limits. We’re now burning fossilised plants, which emits carbon on a one way trip to the warming atmosphere. There was little to no resemblance between the kindling fires we were using and the ones that were being used. There is no generational wisdom that can tell us what we should do when the Central Kalimantan peatlands are drained or dry fuel piles up in the California countryside. All this while raising the temperature to unrecorded highs.

Books About FirePrescriptions are often the end of a typical prescription: We must invest in science, reclaim cultural knowledge lost, burn intentionally and build resilience, as well as power our grids renewalably. All of that is true, I’m sure. Considering the complexity of fire and how unorthodox nearly everything was doing with it, the best advice is to slow down. In a matter of minutes, we have altered our energy habits, altered the climate, and changed our relationship to fire. It is not surprising that fire, once an indispensable, but stubborn companion of our species, has fallen out of our grasp.

The world won’t go up in flames, contrary to what we imagine. But tomorrow’s fires are different from yesterday’s. We are racing to that unsettling future, burning gas as we go.