[ad_1]

China’s CO2 emissions have rebounded from a steep, but short-lived, fall due to the Covid-19 lockdown to reach a new record high, analysis of the latest quarterly data reveals.

Government stimulus measures introduced earlier this year to fire up China’s post-covid economy have seen steel production, in particular, ramp up.

The three-month period from July-September saw steel output in China – which is a source of significant carbon emissions – rise by 10%.

China’s recent surge in steel production has shown that it will likely miss its 2020 targets to reduce steel capacity. Many provinces have reported steel production far exceeding their capacity control targets.

Steel targets

The steel targets were set in 2017, following Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s signature policy of “supply side structural reforms”, which aimsto reduce the dependence of successive waves on construction-sector stimulus.

上微信关注《碳简报》

When upstream coal is used for electricity generation and coking, the steel industry is the country’s largest coal consumer. It is also the largest electricity consumer and the largest source of air pollutant emissions, making it a key target in the government’s efforts to improve air quality.

The capacity reduction targets have been China’s response to complaints from other governments about “dumping” steel on the global market.

The key target set in 2017 was to limit China’s steel production capacity to no more than 1,000 million tonnes (Mt) per year, down from 1,130Mt/year in 2015. However, the steel output is expected to rise by 30% between 2015 and 2020, reaching 1,000Mt this past year. This indicates that the actual production capacity is much higher than the target capacity.

Compared to the maximum output achievable under the capacity target, the “excess steel output” amounts to 200Mt. This is equal to two-and-a-half times the total output of the US’s steel sector. The “excess” CO2 emissions from China’s steel sector will be around 300Mt in 2020 – roughly equal to Poland’s total emissions.

China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) recently released a new policy document on steel capacity, accompanied by government criticism towards the provinces for “gaming the numbers” and loosening capacity controls to chase economic recovery.

Emissions rise

China’s CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel burning and cement production have rebounded rapidly over the last quarter. They increased an estimated 3% year-on-year in the July-September period after falling approximately 8% in January-April – and around 25%During the weeks following the Covid-19 lockdown at January’s end.

These findings are based in part on official statistics and data from China’s energy industry. They are compatible with new satellite-based estimates, published this week in the journal Science Advances, finding that China’s CO2 emissions returned to pre-pandemic levels after April – as my analysis for Carbon Brief first showedReturned in June

Three-month average CO2 emissions from cement production and fossil fuel burning in China, Q1 2015 – Q4 2020. Source: Author’s analysis based on government data from China’s National Statistics Bureau and China Customs, plus energy industry data from Wind Information. Use Carbon Brief to generate the chart Highcharts.

The most recent quarterly data shows that the metal industry, which is dominated by iron or steel production, increased coal consumption by 6%. There was a 10% rise across the construction materials sector (mainly cement production). However, coal consumption in the power sector remained largely flat and fell on aggregate in other areas. In China, there was a 1% increase in thermal coal consumption over the July-September period.

The data also shows that cement production increased by 5%, oil demand increased by 3%, and gas demand rose by 4% year-on. Two thirds of the increase in CO2 emissions can be attributed to just two industries – steel and cement – when the growth in their electricity consumption is taken into account.

Managing steel capacity

China’s MIIT, which is in charge of managing steel overcapacity, published its “steel industry adjustment and upgrading plan” for 2016-2020 back in 2017.

The plan forecast domestic steel consumption at 650-700Mt in 2020. This is a decrease from 760Mt for 2013. It set a goal to reduce steelmaking capacity from 1,130Mt by 2015 to less than 1,000Mt by 2020. The plan targeted steel production of 750-800Mt in 2020, down slightly from 804Mt in 2015 – 100Mt higher than projected demand, accounting for exports.

China does not report the country’s steelmaking capacity systematically. Instead, the average capacity utilisation at large steel firms is reported together with production. The ratio of actual output and capacity is called utilization. Therefore, the amount of available capacity can be estimated using the two time series.

China’s steel output, capacity control target and estimated actual capacity; million tonnes per year. Source: Steel productionCapacity utilisationNational Bureau of Statistics; 2020 projections based on the first ten months of data. Author estimates the capacity. Carbon Brief Chart Highcharts.

In 2016, and 2017, this implied capacity was in line with the new target. Steel production increased slightly, but reported utilisation rose quicker than production, which suggests that capacity cuts were successfully implemented.

However, in 2018, steel production started to surge much faster than the reported capacity utilisation, indicating that steel firms had started to add capacity, perhaps getting better at skirting the government’s controls. The gap between the capacity target and actual production has grown to well over 200Mt by 2020.

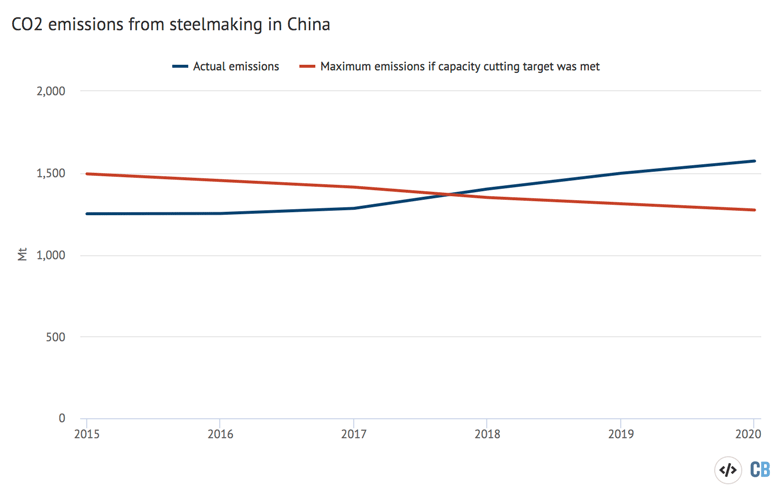

This translated to CO2 emissions means that current sector emissions are approximately 300Mt higher than the maximum emission limit under the capacity target. Even assuming high capacity utilisation.

Based on the steel output, estimated CO2 emissions (Mt), from China’s steel production. The maximum emissions allowed by the capacity control target were calculated assuming a very high utilization rate of 85%. Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the National Bureau of Statistics and average energy consumption per tonne of steel reported by China Coal Industry Association and compiled by the author from news reports. Use Carbon Brief to create your chart Highcharts.

Provincial expansion

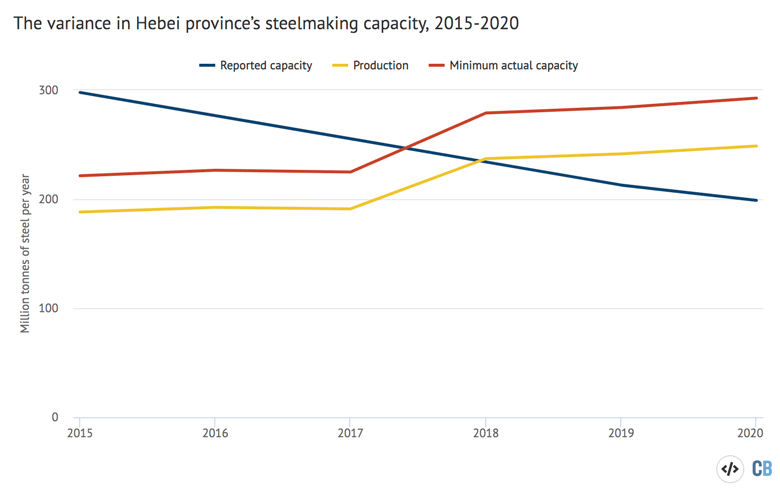

Hebei – the heavily industrialised province surrounding Beijing and the prime focus of China’s efforts to address air pollution – took the lead in implementing these cuts, pledging to deliver one third of the targeted cuts in 2016 and to cut total steelmaking capacity from almost 300Mt in 2016 to 200Mt in 2020.

However, Hebei’s steel production is set to reach a record 250Mt this year, up from 188Mt in 2015, showing that actual capacity is closer to 280Mt. The gap between this actual capacity of reported steel production and the capacity target is almost equal to the annual steel output of the US – and responsible for a third of the gap in China’s national steel numbers overall.

Hebei’s reported steel production far exceeds the amount of steelmaking capacity the province claims to have – and the gap has widened over the past two years. Taking into account that it is not possible for steel plants to produce at full capacity around the year, I have calculated the “minimum actual capacity” based on assuming a very high average operating rate of 85%. This conservative calculation increases the gap.

Hebei’s steel output, capacity control target and estimated actual capacity (Mt). The minimum action capability is calculated as an assumption of a very high rate of 85%. Source: Steel production via National Bureau of Statistics via Wind Financial TerminalBased on the first nine month of data, 2020 projections. Carbon Brief Chart Highcharts.

Hebei reported that 74Mt of its steelmaking capacity was closed between 2015 and 2019, with another 14Mt expected to close this year.

Discrepancies

Hebei’s contradictory numbers make it clear that steelmaking capacity has reached a scale where it is making the capacity reduction targets virtually meaningless.

The MIIT recently invited comments on a policy document called “updated work plan for steel capacity replacement“. The document exposes the issues in the implementation and replacement of capacity control capacity. It reports that 165Mt steelmaking capacity was shut down between 2018 and 2020, and 139Mt was added. This means that one tonne was added for every 1.15 tonnes of closed capacity.

Some local governments have relaxed controls and increased their steelmaking capacity in response to the Covid-19 shock. The new policy plan aims to prevent local governments from “gaming” the numbers and hopes to correct the inaccuracies in the reporting of steelmaking capacity. It requests at least a 1.5:1 replacement ratio in air pollution controls in the key regions, including Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Shanxi-Shaanxi-Henan, Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta – and 1.25:1 for the rest of the country.

One key issue is that the capacity control targets only deal with “registered” capacity. MIIT has a list of registered capacity, but there is a certain amount of capacity that is not on the official lists.

Steel firms are also expanding capacity in production by reporting the closure of old production lines or units that have been out of operation for a long time, but still remain technically “on the books”, and replacing these with brand new production capacity. Many of the announced “replacement” projects do not appear on the ministry’s lists of registered capacity, which means that they are likely circumventing the capacity control system, or possibly operating without proper supervision.

Staying power

As China finalises its next five-year plan – due out next year – and prepares to implement its new 2060 carbon neutrality targetFailure of steel capacity control is a warning signal about the sustainability of emission-intensive industry interests.

The construction-driven recovery from Covid-19 has further increased the country’s reliance on government-directed projects for economic growth.

From the Chinese policymakers’ perspective, the demand for steel has proved far more resilient than expected in the wake of the industrial downturn of 2014-15. This increased demand for steel was a result of government policies that stimulate infrastructure projects and real property. The demand for steel can be controlled by the local governments, just like the supply.

The missed steel capacity targets are evidence of both the political power of the industry, as well as China’s continuing economic reliance on construction and heavy industry to fulfill economic growth targets. This shows that steel output has outpaced GDP growth in 2018 and 2019, which is evidence of this dependence.

There is an opportunity to chart a new economic path with the expected rebound in consumption and services next year.

Research by Xinyi Shen.

This story has sharelines

[ad_2]

Source link