[ad_1]

Forests are where you can find your home. 80%These arks of existence are under threat. The rising global average temperature is threatening tiny plants like Sidebells wintergreenOn the forest floor (also known as the understory). Shift upslopein search of cooler climates. Forest plants can’t keep up with the speed at which the climate is changing – they lag behind.

The rate at which forests adapt is so slow that many species living in forest substories today are probably responding more slowly to changes in their environment. The Mormal Forest floor in northern France is covered in quaking sedge. This grass-like plant is a reminder of the former settlements that were used to make straw mattresses by German soldiers during the first world War.

The land has been impacted by changes in management, sometimes dating back as far as the Middle Ages and even earlier. BiodiversityForest understories. Scientists can use this information to determine how long a species can keep the memories of past human activities.

Jonathan Lenoir, Author provided

Ecologists are turning to technologies like lidarTo rewind time. Lidar works in the same way as sonar or radar. It uses millions upon millions of laser pulses, to analyse echoes and produce detailed 3D reconstructions. This is how driverless cars sense and navigate the globe. Amazing discoveries like the imprints of Mayan civilisation have been made by lidar since the 1990s. Conserved under the canopyTropical forest.

In a new PaperI, along experts in ecology, history and remote sensing, used lidar in order to trace human activity within the Compiègne Forest in northern France back to Roman times – much later than historical maps could ever do.

Illuminating ghosts and relics from the past

Forest floors are more stable than farm fields which are constantly disturbed. The ground beneath the forest canopy could still bear the imprints from ancient human occupation.

This is something archaeologists are well aware of and increasingly rely upon lidar technology to help them. Prospecting tool. It allows them virtually to remove all the trees in aerial images and hunt artefacts hiding below treetops or fossilized beneath forest floors.

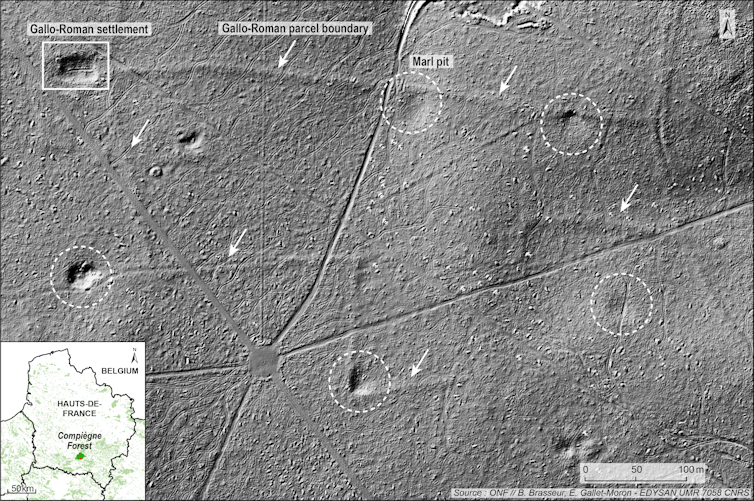

Using airborne lidar data acquired in 2014 over the Compiègne Forest in northern France, a team of archaeologists and historians found well-preserved Roman settlementsFarm fields, and roads. Long considered a remnant of Prehistoric forest, the Compiègne was, in fact, a busy agricultural landscape 1,800 years ago.

Jonathan Lenoir, Author provided

A closer look at these ghostly images of the Compiègne Forest reveals several depressions within a fossilised network of Roman farm fields. This is just one of many depressions that archaeologists found in forests. France, north-easternThey were carved by Romans and the late iron age.

These depressions were created to extract marls (limerich mud) from farm fields to enrich them with carbonate minerals. They also create local depressions that collect rainwater for the benefit of livestock. Marling is still a common practice in northern France for crop production.

Jonathan Lenoir, Author provided

The long-lasting effects human activity has on the environment

These signs of Roman occupation in modern forests provide clues to why some plant species are present where we wouldn’t expect them to be.

On a summer day in 2007 in a corner of the Tronçais Forest in central France, A team of botanists found a little patch of nitrogen-loving species – blue bugle, woodland figwort and stinging nettle – nestled among more acid-loving plants.

Nothing remarkable at first glance. Archaeologists discovered that there were once Roman farm buildings on this spot. Cattle manure likely added nitrogen and phosphorous to the soil.

Kateryna Pavliuk/Shutterstock

If a small group of plants can reveal ancient farming practices that date back centuries or millennia ago, then ongoing environmental changes such as climate change will have similar long-lasting effects. Even if the Earth did not heat, the Earth’s biodiversity will continue to change due to the warming signal. However, this delay will be accompanied by more warm-loving species being established for many centuries.

Just as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeIts mission is to create plausible scenarios for future climate changes. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem ServicesIt attempts to give plausible scenarios for the fate and future of biodiversity. This lag effect is not present in any of the biodiversity models. This means that models are more susceptible to errors when forecasting the fate biodiversity under future climate changes.

Understanding the history of modern forests is a great way to decode their current state and plan for their future. Now, ecologists can travel back in history and explore the forest past using lidar technology. It is difficult but necessary to improve the accuracy and efficiency of predictions from biodiversity models through incorporating lagging dynamic.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Instead, get a weekly roundup delivered to your inbox. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.