[ad_1]

It is difficult to hear the latest news about the climate crisis without feeling anxious.

Allegra Netten, a doctoral student at the University of Prince Edward Island, has found it’s not only she and her friends who are feeling that way.

Third-year student in clinical psychologist is researching a scale that can measure anxiety about climate change. In January, she put out a survey and initially received more than 600 responses from across Canada.

She said, “We certainly did not see high levels people having knowledge about the climate change and worrying about it.”

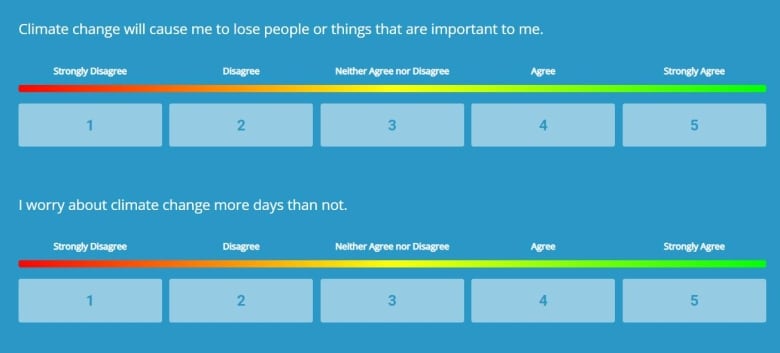

The scale is a 35-item questionnaire, and participants can rate each item on a scale from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree).

How to cope with climate anxiousness

Netten also researched ways to address stress related to the climate crisis, while he was researching the scale.

She said, “One of the biggest things that people can help manage anxiety is thinking about what actions they can take in order to mitigate climate change and adapt to it.”

These actions can include eating less meat or animal products, flying less, or engaging in some kind of activism or advocacy, Netten said.

“Those kinds of activities — if not totally eliminating the anxiety — can help someone to feel less hopeless or less powerless, and feel as though they’re able to take more action to make change in the area that’s concerning them,” she said.

Connecting to the natural world can also be useful in easing climate anxiety, Netten said.

“Doing things that help you feel more connected to nature — whether it’s going hiking or growing your own foods, getting more involved in the environment — seems to be something that is helpful for people.”

Netten noted, though, that feeling stressed when thinking about the climate crisis is a reasonable response.

“It’s really important for us to note that some level of anxiety in response to knowing about climate change is completely normal and, in fact, expected, and might motivate people to engage in more pro-environmental action,” she said.

“But anxiety can sometimes become so severe that it is causing distress or affecting important areas of your life or functioning.

For those experiencing that kind of severe climate anxiety, therapeutic approaches could be helpful, Netten said.

“It might be useful to go work with a therapist, whether it’s a psychologist or social worker or counsellor, and maybe work through some of the different thoughts and emotions that are coming up for you when you’re thinking about climate change and its potential effects on your life.”

The next step

Netten said she will continue the study through the spring and summer. She hopes to make available the scale to the public once that’s done.

She plans to conduct more research around climate change and mental health and further develop the scale, which can help other clinical psychologists, mental health professionals and the public to identify the presence of eco-anxiety.

Netten stated that “a really big extension to this research for me was how can we use the assessment tool to then help people getting better or help manage their anxiety related climate change in a more effective way.”

“So that’s the next step, research-wise and practice-wise, which is to try to figure out what types of therapy techniques might be beneficial for someone suffering from climate change anxiety.”