[ad_1]

Canberra, Australia – As southern Australia continues to recover from the destruction of the 2019-2020 ‘Black Summer’ bushfires, towns in Queensland and New South Wales (NSW) have just experienced devastating floods.

Some towns have even seen ‘once in 100 year’ floods occur twice in several weeks. In Lismore, an NSW town of nearly 30,000 people, the river rose more than 14 metres in late February, breaching the town’s levees and inundating people’s homes and businesses. Thousands of residents were forced onto their roofs to escape the flood waters.

Lismore was flooded again in March. More than 2,000 homes are now considered. uninhabitable.

While Lismore has flooded five times in the past 60 years, this year’s floods were 2 metres above the previous historic high. 22 people died in Queensland and NSW.

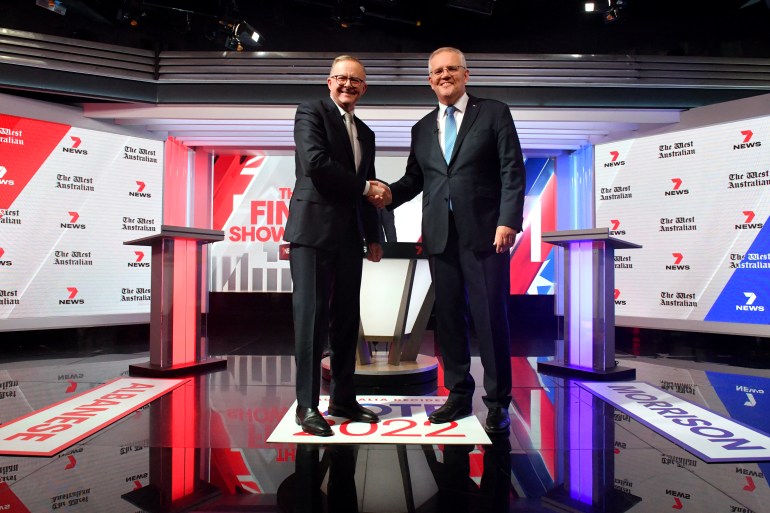

Similar to the Black Summer bushfiresThe federal government has been accused of being too slow in responding to the disaster. Locals relied on their own communities to provide crucial assistance in the immediate aftermath of the disaster and Lismore residents later took their flood-damaged belongings to Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s official residence, dumping ruined armchairs and soft toys at his gate. Some held placards that read ‘Your climate inaction killed my neighbour’.

The cost of the floods is expected to exceed 2 billion Australian dollars ($1.44 bn), making it one of the country’s most costly natural disasters ever.

“Despite decades of warnings from scientists about climate change, Australia is unprepared for the supercharged weather that it is now driving,” said Hilary Bambrick, co-author of Australia’s annual assessment of progress on climate adaptation.

“Australia is at the forefront of severe climate change … Climate change means that Australia’s extreme weather – heat, drought, bushfires and floods – will continue to get much, much worse if we don’t act now.”

Despite this and voters’ desire for action, climate change has barely been a talking point in campaigning for the country’s federal election, which will take place in less than a week on May 21.

“Australians are hyper concerned about climate change,” University of Tasmania political scientist Kate Crowley told Al Jazeera. ”But the major parties, especially the [ruling] Coalition, don’t want to talk about climate change. For them, it’s done and dusted.

“The Coalition has a ‘never never’ target and no immediate plans to do anything, except ensure fossil fuels are in the mix.”

Most politicians in Scott Morrison’s Liberal-National Coalition are climate change sceptics, if not outright deniers, as well as being economically and socially conservative.

Climate writer Ketan Joshi has been tracking politicians’ social media mentions of climate change.

He found that only four percent of tweets by senators and three per cent of tweets by members of parliament mention climate during the first week of campaign. Most didn’t tweet anything about climate change.

“Tweets are a proxy for discourse,” Joshi explained. “It’s a really simple read on [the issue’s] prominence, and it turns out that even when climate is mentioned in bad faith, it’s still only a tiny, tiny proportion of the discussion.”

Joshi believes there are two main causes for the lackluster climate change discussion.

“One is that the issue isn’t prominent enough, considering its physical urgency,” he said. “The second is that when it is discussed, it’s always on the back of something going wrong, as opposed to an initiated effort to talk about a really important issue.”

Since I’m storing tweets anyway, I thought I’d create an auto-generating weekly summary of how politicians and the press gallery are mentioning climate, fossils and clean tech.

Here’s the first week. More features to come in the next report, but for now……you get the picture pic.twitter.com/1baUB5u9BC

— Ketan Joshi (@KetanJ0) April 18, 2022

The only moment when climate change has emerged as a serious point of discussion in recent weeks was when Queensland Nationals Senator Matt Canavan – claiming decisions on climate change could be left for 10 or 20 years time – declared net zero to be “dead” and “all over bar the shouting”.

“Canavan actually put climate on the agenda,” explained Crowley. “The Coalition were quite happy to ignore questions [on it] and just repeat policies … After all, they’ve got a target without really having a target.”

Most voters want action

According to poll after poll, the majority of Australians want their government to take action on climate change.

National broadcaster ABC runs Vote Compass, the country’s largest survey of voter attitudes. In this year’s poll, 29 percent of those surveyed ranked climate change as the issue most important to them. This was even more than any other issue, even the rising cost of living, which 13% rated the most important.

A YouGov poll, conducted by the Australian Conservation Foundation, found that climate change was important to 67 percent of voters in mid-2021. It was also the number one issue in determining who to vote for.

Crucially, a majority of voters in all 151 of Australia’s federal electorates believe that the government of Scott Morrison should have been doing more to tackle climate change. Even in key coal areas like the Hunter Valley, voters didn’t believe that new coal and gas plants should not be built.

Another poll found that young Australians are most concerned about climate change. The Foundations For Tomorrow initiative conducted a survey in 2021 and found that 93 per cent of Australians aged under 30 believe the government is not doing enough to combat climate change.

About 88 percent are eligible to vote in Australia, which is compulsory for all Australians aged 18-24.

Evaluation of the policies

Many voters feel there is little difference between the Labor Party and the Coalition, particularly on issues such as climate change.

Based on 2005 levels, the Coalition has set a goal to reduce emissions by 26-28 percent by 2030. They say they will not abandon the 2005 levels to achieve this goal. Heavy polluting industries like coal and natural gas but instead rely on carbon capture and storage, alongside new low emission technologies. Because they are not yet available, the exact technologies have not been identified.

Anthony Albanese, the leader of the Labor Party, has set a 43 percent emission reduction target for 2030. This is still lower than the expert-recommended target 50 to 75 percent. Labor plans to invest heavily and create 600,000 new jobs if it is elected in May. Labor also has detailed strategies for supporting workers’ transition from fossil fuels to other sectors.

Both Labor and the Coalition agree that net zero should not be achieved before 2050. However, both receive significant donations from mining companies, more than any other sector. Labor, just like the Liberal Party won’t sign the UN pledge that it will end coal fire power if it is elected.

Despite AGL’s high-profile commitment to shut down gas and coal plants sooner than planned, both major parties have committed to supporting fossil fuels.

There are 114 new coal and gas projects on the government’s official register, such as the controversial gas extraction project in the Northern Territory’s Beetaloo Basin. Altogether, these projects would increase Australia’s emissions by more than 250 percent.

Despite the public concern, the Australian fossil fuels lobby has proved remarkably strong, claiming that mining props up the Australian economy – it contributes about 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product and employs 261,000 people – and that without it, financial disaster looms.

The lobby also used class rhetoric in order to place coal mining at the heart of regional working-class politics. This encouraged both major parties to vote for pro-fossil fuels.

The Greens – a left-wing environmental party often referred to as Australia’s ‘third party’ – are the only group to have argued the need for Australia to do more on climate. It has set a high target of 75% for emissions reductions before 2030 and wants net zero by 2035, or earlier. This is primarily by ending the mining, burning and exporting of thermal coal by 2030.

The Greens’ campaign material describes net zero by 2050 as “a death sentence”. The party is calling for a moratorium to new oil, gas, and coal projects.

“The mining and burning of coal and gas are the leading causes of the climate crisis,” said the Greens’ Adam Bandt of the demand.

“Keeping coal and gas in the ground is the very first thing a government would do if they were serious about treating global heating like the climate emergency that it is.”

One big question remains, however.

How much will voters put climate concerns first on election day?

Sometimes, local issues may seem more pressing than they are at the polling stations.

Inflation is at its peak Highest in 20 YearsThis is due to the fact that the price of everyday items like petrol and vegetables has increased as a result of the war in Ukraine and the flooding earlier this year.

Skyrocketing house prices and rents are also at the forefront of many people’s minds, as are key issues that were highlighted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as aged care. The central bank has just Increased interest ratesFor the first time since 2010

“People have very much separated climate and politics,” agreed Joshi. “Someone can see climate change as an important issue, but still have a [negative]Gut reaction to support the Greens.

“It’s worth noting that people will often express strong support for climate action in surveys, but have very confused and mixed views when it comes to its immediacy.”