[ad_1]

OOn a Saturday afternoon, diners at Brooklyn’s Grand Army enjoyed oysters with lemon juice and mignonette. The music was a mix of hip-hop and funk. Unbeknown to many of them, they were also supporting a new effort to use oyster shells as building blocks for new, living coastal reefs – a transformative use that’s not only restorative, but may also help protect the city from climate change.

Grand Army is just one of the many restaurants in the city that donated their oyster shells to restoration projects such as Living Breakwaters, a $107 million effort to protect the coastline. New York City’s Staten Island.

The project will consist almost of a half-mile of submerged breakwaters, strategically covered with recycled oyster coral reefs. As those reefs grow, the project’s designers hope they will help control flooding and coastal erosion while providing new habitat for abundant aquatic life.

In a sense, Living Breakwaters is an attempt to reimagine the relationship between humans and nature in one of the world’s most heavily engineered harbors. It is a departure from so-called gray infrastructure like dikes, seawalls and dams – the tools that largely define New York’s efforts to control flooding.

Instead, the project is designed to protect the city by harnessing the power of the very natural systems that have been all but destroyed by environmental degradation – and reviving them in the process.

Oysters have played a special role throughout the history of New York for thousands of years. Once a staple of the Lenape people’s diet, oysters led European visitors later to write home in wonder of their quality, and colonizers turned them into a major industry – ultimately devastating local oyster populations through pollution and overconsumption.

“We have been living in this world where nature has existed sort of as a backdrop,” said landscape architect Kate Orff, whose design firm Scape conceived of the Living Breakwaters project. “But that background is no longer there, it’s in a state of collapse. We have to foreground the notion of rebuilding natural systems right now otherwise we will not have this bridge to the future.”

Living Breakwaters installed marine mattresses and bedding stones on the seafloor of Staten Island in September. It is the result of seven years worth of planning, permitting, and testing. This was done in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy in 2012, which decimated homes and boardwalks. Federal funding was available to help rebuild. Congress allocating$17bn to New York City alone. The project is based on the belief that building with nature is the best way to meet the challenges of climate change-induced sea levels rise and increasingly vicious storms.

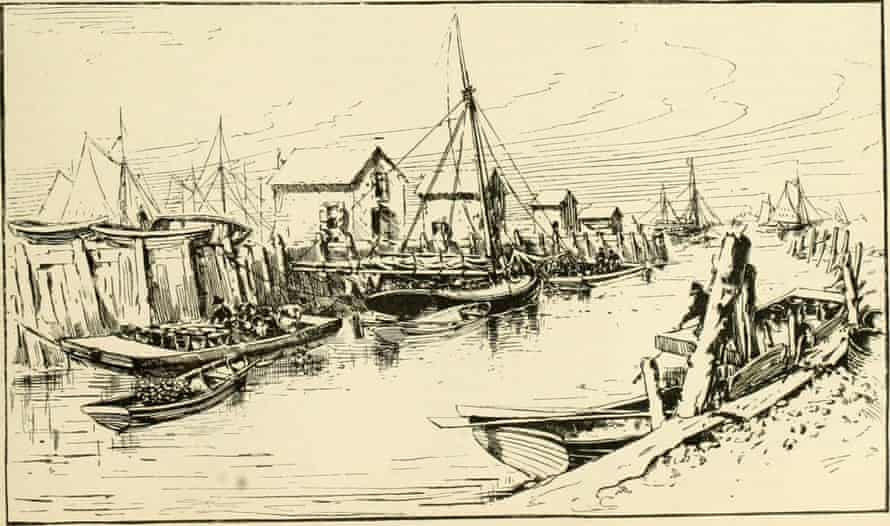

Illustration: Alamy

This so-called green infrastructure approach includes oyster building. The bivalves can be attached in water to rocks and other structures to make them more resistant to the pounding waves. They are also efficient water filters – a single oyster can filter as much as 50 gallons of water a day, sucking out pollution and excess nutrients, and enhancing water quality.

‘It was a nightmare’

Sandy ripped into the New York metro area just under a decade ago, pushing swells not only on to the streets of lower Manhattan – where neighborhoods went dark for days amid the flooding – but also straight into Staten Island, where single-family homes are built right up on the water. The storm, which caused $19bn of damage in 24 states and killed 44 people in New York City, was a major event.

Twenty-four people were killed in Staten Island’s storm, including two residents of Tottenville, where Living Breakwaters is currently being built. Gerard Spero lost George Dresch and Angela Dresch (his brother-in-law) in the storm that tore their house from its foundation.

“The only thing that was left was the front steps and the hole for the basement,” said Spero. “It was a nightmare. A total nightmare.”

The federal and local governments invested money in strengthening the coast after Sandy. New York City began construction on a $1.4bn facility last year. Project to bolster defenses on Manhattan’s east side through a series of raised parklands, floodwalls, berms and movable gates. Some wondered if green infrastructure solutions could be more cost-effective than traditional projects because they are intrinsically regenerative.

To find those projects, Shaun Donovan, who led the federal government’s long-term Sandy recovery and was then the secretary of the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (Hud), said the agency launched a competition called Rebuild by Design, inspired by efforts in Amsterdam to bolster its considerable gray infrastructure apparatus through nature-based solutions to high-water management.

Living Breakwaters – which took lessons from Louisiana, where oyster reefs have been installed in lakes and bayous for over a century – presented an opportunity to test out nature-based defenses hundreds of feet off the coast of America’s largest city.

“One of the things about a crisis the scale of Sandy is, essentially, when it’s a 100-year storm, nobody’s alive that’s seen an example of it, right?” Donovan said. “What any place, even a place as sophisticated and innovative as New York needs to really do, is look at what’s happening around the globe, bring the best thinkers, and almost invent new solutions.”

OLiving Breakwaters set to work on a winter morning installing armor stone near Staten Island. Danielle Bissett was the director of restoration for Billion Oyster Project. She boarded a ferry in Lower Manhattan and rode it across to Governors Island. Bissett is in charge of helping to revive New York Harbor’s oyster population by literally incubating a billion oyster larvae on used shells from restaurants across the city.

That restoration is necessary as a result of two centuries of dredging by the US army corps of engineers, and the accompanying industrial waste and raw sewage that made its way freely into the city’s waterways before state and federal reforms in the 1960s and 1970s slowly started improving water quality. While dredging helped turn the city into an economic powerhouse, it also decimated places like the Buttermilk Channel, a small waterway once home to oysters and tide pools that was shallow enough at low tide for people to cross by foot from Brooklyn to Governors Island, where Bissett’s office is today. The channel is now deep enough to accommodate cruise ships.

The shells that will be oysters again are stored on the island in 10ft mounds. They are then transported by a big truck from city restaurants. These piles recall the older oyster shell piles that were left behind by Lenape and other native people long before Henry Hudson and his 16-member Dutch, 16-British crew sailed into New York Harbor. Lower Manhattan’s Pearl Street was named after one such midden.

Bissett and her team will begin seeding the stone breakswaters with larvae-laden oysters after the foundational work on the Living Breakwaters is complete in 2024. The Billion Oyster Project, which launched in 2008 with the goal of restoring one billion oysters in New York Harbor by 2035, is hoping this year to hit the 100m oyster milestone – the number of oysters implanted with larvae and “installed” in various areas in the harbor.

“If we don’t intervene and help it’s tough for nature to get a foothold,” she said. “The most exciting part of all of this is it’s not just oysters. It’s wetlands. It’s the intertidal zone and that rehabilitation. It’s water quality.”

For Staten Island’s coast, that rehabilitation may find its roots on pebble ice with a helping of cocktail sauce.