China’s cities are facing worsening urban flooding and are turning to nature to build what is called “sponge towns”.

Instead of relying solely on the “gray infrastructure”, which includes pipes, dams, pipes, and levees – sponge cities allow urban areas absorb water during periods of high rainfall and release it during drought.

These concepts could be used in cities across the world to combat flooding, absorb carbon dioxide, increase animal and plant life, and expand green spaces.

Kongjian, dean of Peking University’s College of Architecture was the pioneer of research into sponge-city technology and has spent more then 20 years advocating for their adoption in China.

He believes that the current approach to building concrete barriers and covering permeable surfaces is doomed. Instead, cities should adopt nature-based flood control strategies.

PIN IT

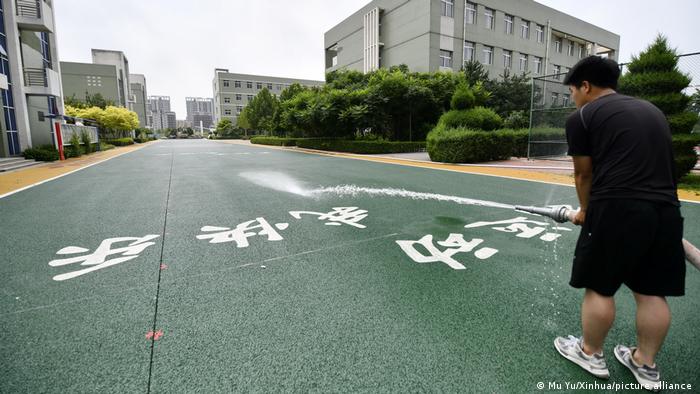

PIN ITThis porous surface allows water to seep into it

A flexible solution

The issue was thrust into the spotlight when flooding swamped Beijing in 2012, crippling the city and killing scores of people. Floods in China and other developing countries like India and Bangladesh are often attributed to rapid urbanization and destruction of wetlands. These natural sponges trap and release water slowly and can be blamed for flooding.

Yu claims that tropical cities made a mistake in adopting the same water management systems as those in Europe’s mild climates. This can lead to severe damage.

His ultimate vision of a city without gray infrastructure is one that includes wetlands, green areas and permeable surfaces. He also envisions a city with widespread vegetation, wide roads, and open areas near roads.

The Chinese Central Government adopted Yu’s ideas in 2013, and the plan was expanded to 30 cities. After successful trials, cities are now required to build sponge city elements. Authorities aim to convert 80% of urban areas to sponges by 2030.

PIN IT

PIN ITChina’s rapid urbanization has made it more vulnerable to flooding.

These are the basic tenets

The basic principle of sponge cities is to give water enough room and time drain into the soil where it falls, rather than channeling it away as quickly as possible and sequestering it in huge dams.

Instead of creating water channels that are fast-flowing, sponge cities slow down water flow in meandering streams with no concrete walls and plenty of room to spread out during heavy rains.

Yu claims that replacing concrete infrastructure could save lives.

“Failed dams are killing a lot of people not only in China but also in America.” Because you have He said that a dam is not necessary because you don’t have one. He stated that even if the system is larger, with a thicker, more robust pipe system, it will still fail 10 years later or even one year later. It’s not an adaptive solution. It’s fighting against nature.

PIN IT

PIN ITSponge cities are built on natural waterways that meander or slow down water.

Water cleaning

The natural waterways, permeable soils and sponge city designs are ideal for clean water and reducing pollution.

Rainwater can cool the city by evaporating. Rainwater can also be used to cool the city.

Yu says vegetation, sediments and microorganisms in sponge city water systems could eventually replace a lot of energy-intensive urban water filtration systems, or least reduce the burden on them.

Stopping floods

Yu claims that if only 1% of the land is used for water drainage, most flooding can be stopped. In the case of biblical, 1-in-1000-year floods, 6% of land allocated to water drainage would be enough to stop the damage, Yu says.

He also says that cities should be prepared in case of flooding by building buildings that allow for rising water levels.

PIN IT

PIN ITWetlands help combat climate change while preserving biodiversity

Fight climate change

As climate change worsens also do Katastrophic weather conditions. These cities are subject to more unpredictable rainfall and may overwhelm current systems.

However, sponge cities are seen as a way to mitigate climate change and also act as a way to combat it.

Sponge city infrastructure takes less energy to maintain than gray infrastructure. It reduces the demand on water treatment facilities and reduces the need for air conditioning. Construction requires fewer resources, including less concrete. And sponge cities contain large green spaces that absorb carbon dioxide.

Proponents of the plan say that if adopted worldwide, it could make a big difference in climate change mitigation and reducing flood risk.

PIN IT

PIN ITLarge recreational areas can be doubled by green spaces that absorb water.

Recreation and biodiversity

These green spaces have the added benefit of promoting biodiversity, which is a key threat to humanity along with climate change.

The wildlife and plants that thrive in wetlands and forests are more likely to flourish. And these expanding green areas provide more recreational space for residents, says Faith Chan, associate professor at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China.

Chan, who studied sponge cities extensively and helped to implement it in Ningbo (150 km (93 mi) south of Shanghai, said, “Most of our community loves to have urban parks, to enjoy recreational.”

PIN IT

PIN ITThe concept could be beneficial for the developing world, according to the proponents.

An option for developing cities

Many of the sponge cities movements have taken place in already developed urban centers. Proponents claim that there is great potential to incorporate these ideas into the planning and design of cities that are less well-established.

“In developing countries they look to London, Paris, and Berlin to build their cities. Yu says that the tragedy is when they build this kind of infrastructure, and it fails due to climate change and the monsoon weather.

Chan says that countries with less financial resources are able to save money by planning ahead.

Retrofitting the entire area to be a green space or nature-based solution is the most expensive. “Maybe the area is already farmland or a forest when you build new districts. You can save money by doing a little engineering to manage drainage.

PIN IT

PIN ITVegegation, which is also used to create sponge cities such as rooftop gardens, is a key component.

What about Europe?

Europe has seen worsened floods as climate change alters weather patterns. In 2021, devastating rains caused hundreds of deaths in Germany and Belgium.

Yu believes that much like Berlin tore down a wall dividing East and West three decades ago, it is time to start dismantling grey infrastructure and replacing it by sponge city concepts.

Some European countries have started to adapt. Low-lying Netherlands has been allocating large areas to absorb floodwaters since the 1990s as part its “Room for the River” project. One case sees the area doubled as a rowing track.

Chan claims that scientists and policymakers in China and Europe are increasingly exchanging information about the development of nature-based solutions.

Chan says, “I believe in Europe, especially in regions that have more rainfall, I think they could learn from Chinese experiences as well.”

Edited by Tamsin Walker & Jennifer Collins