[ad_1]

The Maldives’ aerial view is stunning as you descend into the country. In two rows 1,200 turquoise rings line the Indian Ocean, running along the Chagos Laccadive Ridge. The coral islands that connect the lowest-lying country of the world are like a delicate necklace.

Just after landing, the country’s rapid transformation is apparent in the many newly-built high rises and construction sites. In the background, Malé is just a stone’s throw away. The capital, which is just a meter above the sea level, sits right in the middle of more than twenty coral atolls. It is home to 200,000 people who vie for space every day and pay a premium for it. The remainder of the country’s population is scattered throughout the rest of its 200 inhabited islands and lives in a vastly different reality.

The maritime nation has, unsurprisingly, built its economic existence on its coast riches. For generations, it relied on fishing, but today, it relies largely on tourism. With 80 percentThe vast territory of the country, which is less than one meter above the sea level, means that the population of 500,000 is acutely aware of the dangers of the sea. This means the country’s “cash cows,” highly fragile ecosystems, are at the mercy of future climate volatility.

A fisherman sits in his boat in the Malé harbor after weeks at sea. Fisherman’s life is becoming more difficult due to declining catches, high fuel costs, and illegal fishing by foreign ships. Nicholas Muller.

The Boxing Day tsunami was a crisis in 2004. It occurred within an hour of a powerful earthquake in the Indian Ocean. Without warning, most of the Maldives were submerged and the tsunami resulted. Inundating the capital This is causing extensive infrastructural damage across the country.The financial cost was more than half a million dollars with almost half of the country’s GDP erased. Entire islands were rendered uninhabitable and abandoned; droves of people relocated to Malé in search of a better, more stable life.

Enjoy reading this article?Click here to subscribe and get full access. Just $5 per month

External pressure following the tsunami led eventually to constitutional reform and a new constitution being created in 2007. In 2008, the country’s first democratically elected leader was Mohammed Nasheed. He advocated for more urgent climate action in particular for small and vulnerable states. The Maldivians began to feel more concerned about climate issues as a result of a renewed sense for urgency in addressing the threat.

It was difficult to explain climate impacts to the people of a deeply religious country. Nasheed was elected to the presidency at the beginning of his term. Submitted the New York Times, “For your average fisherman, who feels very insignificant in front of God, they are finding it difficult to understand the connection between climate change and human activity.”

A fishmonger prepares a yellowfin tuna just delivered. Tuna fishing was the backbone of the economy before the boom in tourism. Nicholas Muller.

After Nasheed’s famous underwater cabinet meeting ahead of the 2009 Copenhagen Climate Change Conference (COP15), he told reporters, while still wearing full scuba gear, “We are trying to send our message, let the world know what will happen to the Maldives if climate change is not checked. This is a challenging situation and we would like to see that people actually do something about it.”

After COP15, he assessed the gravity of the situation and he , “We worked really hard for a deal in Copenhagen. In hindsight, when you look back at the Maldives, it becomes clear how impossible this whole thing is. You’re having to spend less on health care, less on education, and then use that money on concrete and sea walls.”

A woman in Hulhumalé goes for a morning swim with other women in a program meant to teach more people how to swim. Many Maldivians don’t know how to swim despite living near the ocean. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Massive Changes

Over the last three decades, Maldivians have flocked to Malé from the outer atolls seeking better services, employment opportunities, and access to schools. Space quickly ran out, as was expected. Malé’s booming urban population constantly tested the island’s capacities to provide water, electricity, and other basic services to its citizens, motivating the government to try and alleviate the situation.

Return to 1997, Hulhulé Island, just across from Malé, was a mere airstrip tasked with quickly shuttling arriving tourists onto private boats or small seaplanes that took them to faraway resorts. A quarter of a century later, the landscape could not be more different: Two separate lagoons have been transformed into a new, connected island attaching artificial Hulhumalé to Hulhulé by road.

Maumoon Gayoom, then President, started the project.o primarily ease congestion for Malé residents and spur economic development, the country went “all in” on population relocation to Hulhumalé. Planned in two phases, the intention of the “City of Hope” (in Divehi) was to be the antithesis of Malé: spacious, higher, orderly, and more livable. Millions upon millions of tons of sand were taken from the ocean to create the artificial island. The island was two meters higher than sea level in order to protect it against future sea inundation. With the completion of the first phase, tens of thousands relocated from outer islands and from Malé to Hulhuhmalé.

Enjoy reading this article?Click here to subscribe and get full access. Just $5 per month

Phase 1 of construction on Hulhhumalé was finished in the 2000s. Tens of thousands now live on the island. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

In 2018, Malé, Hulhulé, and Hulhumalé were connected with a 2-kilometer bridge which cost $200 million and was financed by Chinese loans. A substantial amount was also borrowed to expand the airport. The country is still sorting out the “debt mess” accrued under then President Yameen, whose spending spree is estimated to EqualAbout a third (33%) of the Maldives’ entire GDP comes from corruption. Corruption had become “normalized,” Mariyam Shiuna, executive director of Transparency Maldives told the Financial Times in 2019. “Allegations of corruption were widespread in President Yameen’s time, and whenever people questioned it, the response was that you don’t need to know.”

Much is still unknown about the Maldives’ debt situation concerning China. “The [Chinese debt] bill was $3.1 billion,” Nasheed, now speaker of parliament, According to the BBC, 2020. The Chinese ambassador to Male, Zhang Lizhong, replied, “China never imposes additional requirements to the Maldivian side or any other developing country, which they do not want to accept or against their will.”

In 2018, the China-Maldives Friendship Bridge (Sinamalé) was opened, linking Malé, Hulhuhmalé, and Hulhulé for the first time. The 2-kilometer bridge was funded by a $200 million loan from the Chinese government and has increased development on Hulhumalé. Nicholas Muller.

Despite the rapid expansion of Hulhumalé, it is not yet a viable economic alternative to Malé for most Maldivians. However, this is set to change as Phase 2 continues construction and targets 100,000 more people to move to Hulhumale.

In the next few decades, Hulhumalé could house up to a quarter of a million people, three times more than currently live in Malé, in different types of housing. Social housing is available for those from the capital and outer atolls. It is widely believed that more than half of the world’s population will live there within a decade.

Large spatial inequalities complicate the government’s work, as it is increasingly expensive to provide logistical support and services across the country. OVer 90 percentMany Maldivians are poor and live in the outer atolls.

A cluster of buildings on Hulhumalé was financed by Chinese loans under former President Abdulla Yameen. $646 million for the housing project went to the Housing Development Corporation, the Maldivian company responsible for Hulhumalé. Nicholas Muller.

“Those who stay on the outer (inhabited) islands face crowded conditions, so reclamation is an extremely popular policy. But it is not without controversy though as much of the construction is done haphazardly and destroys natural coral and beaches,” said Paul Roberts, an advisor to Nasheed.

According to the Asian Development Bank, “The government has finalized a National Spatial Plan (NSP) which focuses on a 20-year roadmap for infrastructure, spatial development, and decentralization. Therefore, the NSP’s focus is on development across all the islands and to reduce the overcrowding and congestion in the capital where approximately 300,000 live in an area of 8.3 square kilometers.”

“Five people can sleep in one bedroom and 10 in one apartment. There are still a lot of people who are choosing to relocate to Malé, ” Roberts said.

The country has moved from a coercive approach to relocation under the former administration to giving people an option whether they want to relocate to Hulhumalé or not. “The whole election (2018) slogan was centered around that (issue). Relocation was completely scrapped and people could remain on their local islands,” Roberts said.

The city of Malé is one of the most crowded places on Earth. Residents live in cramped conditions and high prices, often with multiple family members living close by. Nicholas Muller.

A Heavy Burden

Under Nasheed’s administration, the Maldivian government made climate change adaptation a top priority, and today the country spends 30-50 percent of its GDP annually on adaptation and mitigation measures around the country. “Adaptation is expensive, we are already spending more than 30 percent of our expenditures on adaptation: desalination, water systems, irrigation systems, harvesting issues, on flood defenses, coastal erosion, sand migration, and many other natural disasters,” Nasheed said before COP26 in Glasgow.

Enjoy reading this article?Click here to subscribe and get full access. Just $5 per month

Last year, the Maldives released UpdatedTargets in the NDC (National Determined Contribution), report and now aims To reduce 26 percentreducing its carbon emissions and achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2030 (subject to increased international financial support).

The Maldives’ islands are only one meter above the sea level and are prone to coastal erosion. They rely almost entirely on rainwater and desalination systems. Nicholas Muller.

The most recent IPCC reportThe country’s dire situation is illustrated in the August 2008 report. The U.N.’s climate panel said “limiting global warming close to 1.5 degrees Celsius or even 2 degrees Celsius ‘will be beyond reach’ in the next two decades without immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.”

For small states like the Maldives, the report says that global warming “is dangerously close to spiraling out of control.” Small island developing countries (SIDS), including the Maldives, Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands, were labeled as having a “disproportionately higher risk of adverse consequences of global warming.”

For many years, Nasheed has been the main climate voice for Maldivians as well as other small states. Referring the IPCC AR6 Report, he said, “This report is devastating news for the most climate-vulnerable countries like the Maldives. It confirms that the world is on the verge of extinction. We are at the forefront of climate emergency, and it is getting worse. Our nations are already battered by extreme climate.” A NeueThis month’s IPCC report is expected.

Workers from a northern atoll unload bananas in Malé. The capital is overcrowded and has very little agriculture. This poses a significant risk to future food security. It also increases dependence on imports. Nicholas Muller.

This is already happening in outer atolls. Residents on the most densely populated islands in the north Maldives have offered to evacuate as tidal waves become the norm. Half of the country’s inhabited islands have already reported coastal erosion, with more than 30 islands in a severely eroded state.

It is difficult to pay for these climate costs, despite the urgency. “One of the very difficult issues that we have is our debt. Many countries in need are burdened by debt. It is costly to spend money on adaptation, reclamation and embankments. To do this expensive work, we would need the funds. Because we already are in so much debt, whatever assistance that we get would go right to the debt holders,” Nasheed told NPR last year.

Many locals commute from Hulhumalé to Malé for work each day by ferry. Nicholas Muller.

Glasgow Disappointments

Twelve years later, just before COP 26 in Glasgow, Nasheed shifted his climate message, saying, “I see more people talking about adaptation instead of mitigation. We all will lose. It’s not just the Maldives.” After the new agreement in Glasgow, statements from the Maldives delegation indicated disappointment.

President Ibrahim Solih Tweeted, “The Maldives welcomes the Glasgow Climate Pact that was agreed to at #COP26. The critical 1.5C is still in existence. There is still much work to do. The Maldives calls upon all nations to do all that is necessary to ensure that climate ambition becomes climate reality.”

Maldives’ Environment Minister Aminath Shauna, that the latest agreement was “not in line with the urgency and scale required” and “the difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees is a death sentence for us. What looks balanced and pragmatic to other parties will not help the Maldives adapt in time.”

“COPs are always disappointing and are always watered down to the lowest common denominator. There were many positive outcomes, however. A new renewable energy target was established which has the potential of transforming South Asia and will be a great asset for the Maldives-Indian. solar industry,” said Roberts.

An aerial photo of the crowded capital of Malé, one of the most densely populated places in the world. Nicholas Muller.

Enjoy reading this article?Click here to subscribe and get full access. Just $5 per month

A Financial Conundrum

As a “middle-income” country, the Maldives is in a tight financial spot: not eligible for a lot of development assistance in many cases, but also unable to access affordable loans with low-interest rates because of political instability and high climate risks. The U.N. created Funds specifically to help climate-stressed countries, but the money isn’t coming quick enough.

“There is no financing coming from the Green Climate Fund so far for the Maldives. It’s extremely difficult to access these funds,” Mark Lynas, climate expert, who advisesNasheed discusses climate and works with the 48-member group Climate Vulnerable ForumThe Diplomat, by..

More than 12 years ago, there were promises by wealthy countries for $100 billion in “climate finance” to help climate-vulnerable countries adapt and protect themselves from future climate impacts. According to NPRMany of the funding came in the form loans instead of grants. This, according to developing countries, further strains their climate efforts because they have to repay them. The Maldives need an estimated $9 billion.

The Maldives has very little protection against storm surges or future sea level rises. Nicholas Muller.

“Climate financing is way too slow and redundant, the money will likely never come,” Roberts said. “There have been two projects since 2009 and they were impossibly bureaucratic. The problem is that it is difficult to finance its efforts to net zero. The costs are too high and fossil fuels so cheap. Due to political instability, debt problems, storms and climate-related risks, interest rates are high at 10 percent. If they can focus on access to cheap capital, that would unlock the free market.”

COVID-19 is making it harder for the government achieve its climate goals of future emission reductions and resilience. “Whatever we have budgeted for climate finance in our national budgets has gone to dealing with the pandemic,” Foreign Minister Abdullah Shahid Recently said.

A yellowfin tuna sits in a bucket at the Malé fish market. The resorts sell a lot of the best fish, rather than locals. The sector is still vital to local food security and income. Nicholas Muller.

New forms of resilience

Aside from the giant ongoing construction on Hulhumalé, there are numerous other projects in the works around the country. This year, the Netherlands-based company Dutch Docklands is due to start construction on the world’s first sustainable “Floating city” to mitigate climate effects and stay on top of rising sea levels, which will be eventually connected to Malé.

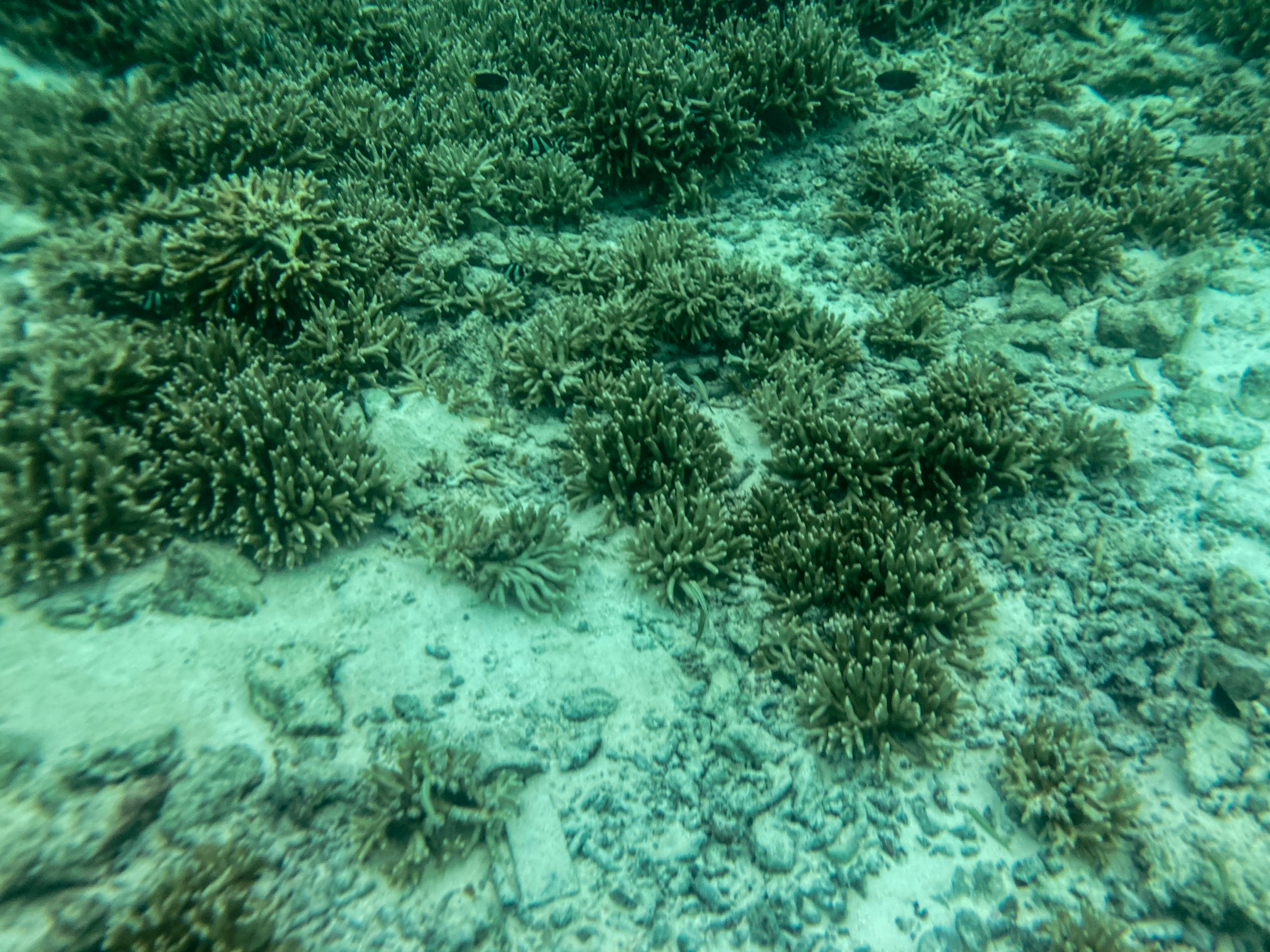

The project should be less environmentally harmful compared to the dredging necessary to create Hulhulmalé, which has been harmful to the coral reefs that serve as the literal backbone of the country’s physical geography. Coral is a It is crucialAs a natural buffer against storms and protects underwater life, coral plays an important role in coastal protection. Coral Transplants from resistant species are being “installed” into dead coral areas around the country to survive warmer currents.

“The floating city is good for allowing housing without land reclamation by Dutch Docklands,” Roberts said.

The Addu Atoll is home to the CreationAnother solution is to create artificial reefs using 3D printing. Floating solarThe panels can be placed on outer islands to create lagoons with a calmer sea. After a long wait, the panels were finally installed in June. campaignEnvironmental activists led by the advocacy organisation. ParleyThe government Prohibited single-use plastics.

The warming ocean temperatures have bleached over 60% of the corals in the Maldives. The coral plays an important role in the prevention of wave inundation in the low-lying island country. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Uncertain Future

Enjoy reading this article?Click here to subscribe and get full access. Just $5 per month

“It’s going to be very difficult for us to adapt to climate change issues if we do not have a solid and secure democratic governance,” Nasheed In 2012, he resigned after being threatened with a coup only four years after he was elected.

A fallback to the old regime could mean that climate mitigation efforts will be halted completely or canceled by a new administration. Last May, Nasheed SurvivedAnother assassination attempt was made on former President Abdullah Yameen in late November. ReleasedFrom jail

30 years of dictatorial rule ended with 2008’s election. But politics have been going on for decades. TurbulentSince then, the country has been home to me. With the next presidential election coming up in September 2023, “there is a huge risk in terms of backtracking,” Roberts said.

At a nearby surf spot, Hulhumale’s new construction towers are easily visible. Nicholas Muller.

As for Hulhumalé, a flood assessment detailed in a recent report Conclusion that Hulhumalé is “built sufficiently high to be safe from flooding under present extreme still water level conditions and with these conditions combined with wave events. This indicates that Hulhumalé is likely to be safe from flooding during the 21st century, as long as the sea-level rise is less than 0.6 m.”

Fishing boats sit in the harbor on Malé. Fishing is the country’s largest industry, other than tourism. Many need to travel further to fish because of the decline in fish stocks due to overfishing. Nicholas Muller.

“If we remain at the Paris levels [2 degrees Celsius] the islands should be OK. Hulhumalé should be enough, although environmentally it’s not great. Sea level rise [alone]This is not an existential threat, but [sea level rise]Extreme storm surges increase the risk. Malé should also be fine with adaptation measures until the end of the century depending on sea-level rise,” said Lynas.

Despite the resilience and long-term survival of Maldivians, who have lived by the sea for generations for their country, it cannot wait for more durable solutions. Many other islands in the Maldives are also at risk. The erosion that continues to erode the land is one of the most common threats. difficulties in disposing of Waste, and a constant freshwater shortage. “Our islands are slowly being inundated by the sea, one by one,” Solih, the current president of the Maldives, said at COP26. “If we do not reverse this trend, the Maldives will cease to exist by the end of this century.”

[ad_2]