[ad_1]

Many years of thought have been spent on how Maine should respond in the face of climate change. But what about the potential benefits? Scientists believe climate change could have positive effects on some parts of the state, including milder, more pleasant winters, lower mortality rates, and an increase in population.

One national modelPiscataquis County has been ranked among the top five climate-advantaged regions in the country.

This story is part our series “Climate Driven: A deep dive in Maine’s response to climate change, one county at time.”

Some scientists are predicting that over the coming decades life could get markedly easier in interior New England — including Maine’s highlands — thanks to global warming. The most important factor in the analysis is warmer, longer winters.

Because the cold can be fatal in interior Maine.

James Rising, a member from the Climate Impact Team, says, “Anyway that climate change reduces cold days each year it’s going to decrease your death rate.”

The Climate Impact Team is an international research group that aims to transform climate data into useful models for the future. Their work fuels public discussions about potential climate “winners” and “losers”.

“Climate change will make Maine’s lives a little better. It’s going to make disease and disability and death all less likely as a result of (generally warmer winter temperatures),” Rising says.

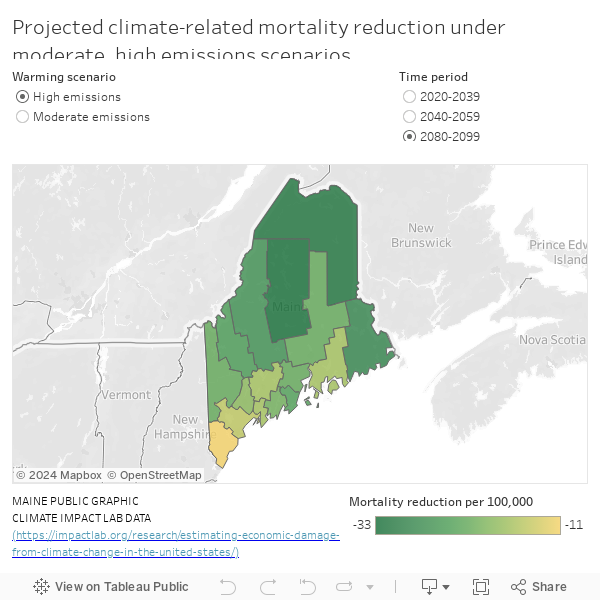

Even after taking into account deaths from storms and hot summer days, he believes that every Maine county will see a reduction in mortality.

York County’s annual death rate will drop by nine per 100,000 under moderate climate-change scenarios. Further from the coast, the rate drops more, with a potential drop of 20 deaths per 100,000 in Piscataquis County. Maine’s annual death rate from car accidents is just 12 per 100,000.

“In terms public health, that’s huge victory, right?” Rising says that this makes a huge difference.

The county’s gross income may increase due to other factors such as lower energy costs and a longer growing period. All of this could make Maine’s interior highlands attractive to people who are forced to move to less-habitable areas.

“Reality prevails. “Reality prevails.”

“We, as a county, need more people. We are losing population and our population is aging. There is theoretically a huge benefit to people moving to our region. Are we ready for that? Fernow says, “I would have to admit at the moment that I don’t believe we are.”

Others in Maine have been considering such possibilities for some time. David Vail, an economist at Bowdoin College, wrote a piece for the Maine Policy Review in 2010 asking whether droughts and fires in Southwest might attract climate migrants.

“I was half serious. Vail states that Vail was certain to be thinking more long-term than the 12 year period since the article was published.

But he writes it in a NEW article, it’s quickly become quite serious. Manifest climate-driven catastrophes — and the example of Maine’s pandemic-driven newcomers — show that the state’s rural “rim” counties have a new chance to reverse decades of losses.

“The rim countries had been suffering from a loss of population and economic activity for many decades. What can be done to turn this around? I believe climate can play an important role in that. Yes,” Vail says.

It’s not that Piscataquis County will be swept away by a tide of humanity — one demographer says that as climate refugees head up Interstate 95 they’ll tend to turn right, towards the coast, seeking more infrastructure and amenities.

Vail sees the potential to attract some of them inland by investing in rural towns centers, parking and housing, as well as health care and broadband. Combine those with a multi-faceted strategy for new forest-products industries, some marketing, and a recent influx of federal workforce and infrastructure funding — a rural renaissance is a real possibility.

A former student said that it was a “silver-buckshot approach”.

He says, “The 100 small ways that things such as cross-laminated lumber, biochar, wind power arrays or high-end tourist resorts on Moosehead Lake can be combined can be the silver buckshot that when we add them together might be able generate the critical mass that is needed.”

The area’s positive outlook on climate is due to its altitude and exposure from dry, cooling fronts from Canada. According to Ed Hummel, a Garland-based meteorologist.

He adds that, even though the extreme heat will take longer to reach us, the changes happening around us and within the region are still going to impact us.

Hummel states that intense rains, frequent freeze-thaw cycles and a smaller snowpack are becoming more common.

He says, “So fishing, farming and anything that has to do with the forest timber industry, that’s all going be affected.”

And there will be more humid days that reach dangerously above 90 degrees — which is why the Dover-Foxcroft Climate Advisory Committee’s first project is to establish a dedicated cooling center for the area.

Lesley Fernow, a member on the committee, believes there are many other tasks that will need to be done to build resilience and make sure resources are equitablely allocated in case the area becomes a climate refuge.

Fernow says, “And truthfully that means in some aspects that humanity has failed if people are migrating into Piscataquis County form places that are unlivable due to flooding, or excessive heat, or they can’t grow food, then that’s going to be considered failure.”

Piscataquis County, she says, could be a sort of climate consolation prize — but that hardly makes it a climate “winner.”

window.fbAsyncInit = operation() {

FB.init({

appId – ‘107525016530 ‘

xfbml: true

Version : “v2.9”

});

};

(function(d, s, id){

var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0];

if (d.getElementById(id)) {return;}

js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id;

js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js”;

fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);

}(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’));