[ad_1]

Climate Emergency

Greenpeace demands more substance from the Government in order to combat climate change. David Williams reports

New Zealand farming’s addiction to synthetic nitrogen fertiliser is now causing more than double the greenhouse gas emissions of domestic flights.

It’s another twist in the country’s arm-wrestle between the economy and environment, an issue that has seen its reputation take a hit internationally over what’s been described as the “dirty truth”.

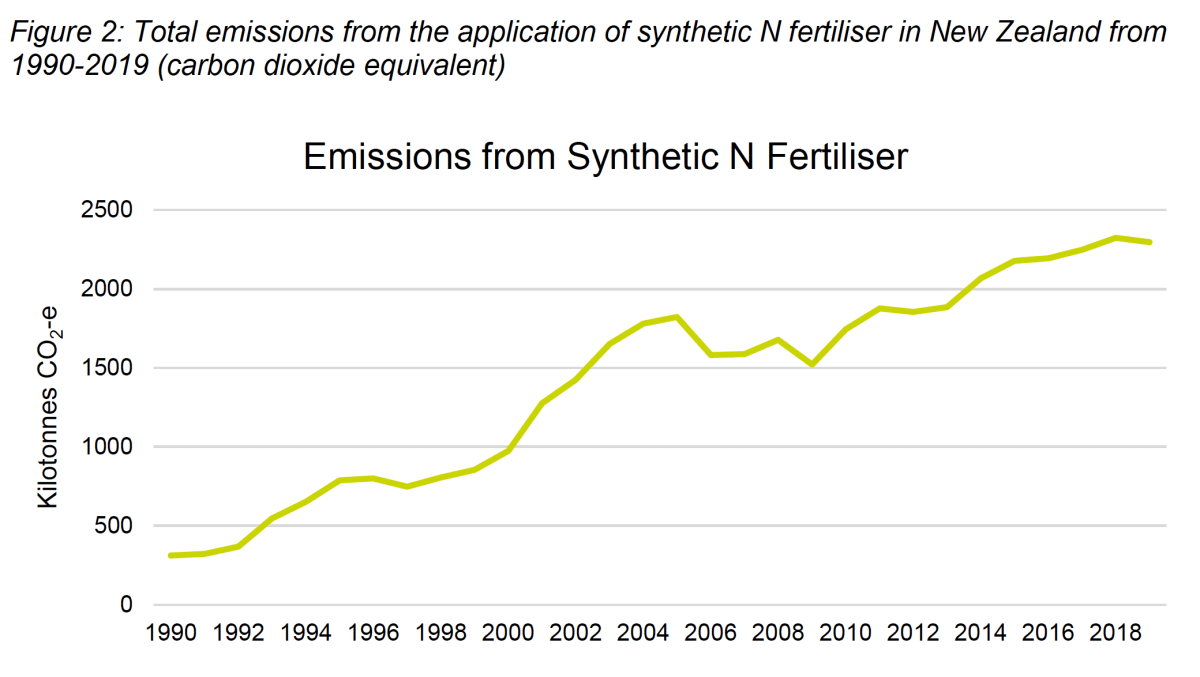

The country’s latest greenhouse gas emissions inventory, published last October, shows direct emissions from synthetic nitrogen fertilisers in 2019 were 2.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions (Mt CO2-e). That’s a 636 percent increase since 1990.

Emissions from domestic aviation in 2019 – pre-Covid – meanwhile, comprising jet kerosene and aviation gasoline, were a touch over 1 Mt CO2-e.

“It’s shocking,” says Greenpeace Aotearoa’s senior agricultural campaigner Christine Rose.

“We need to wean ourselves off the synthetic nitrogen fertiliser addiction. It’s unrealistic to think that we can continue to pollute our climate and our waterways, the way we have.”

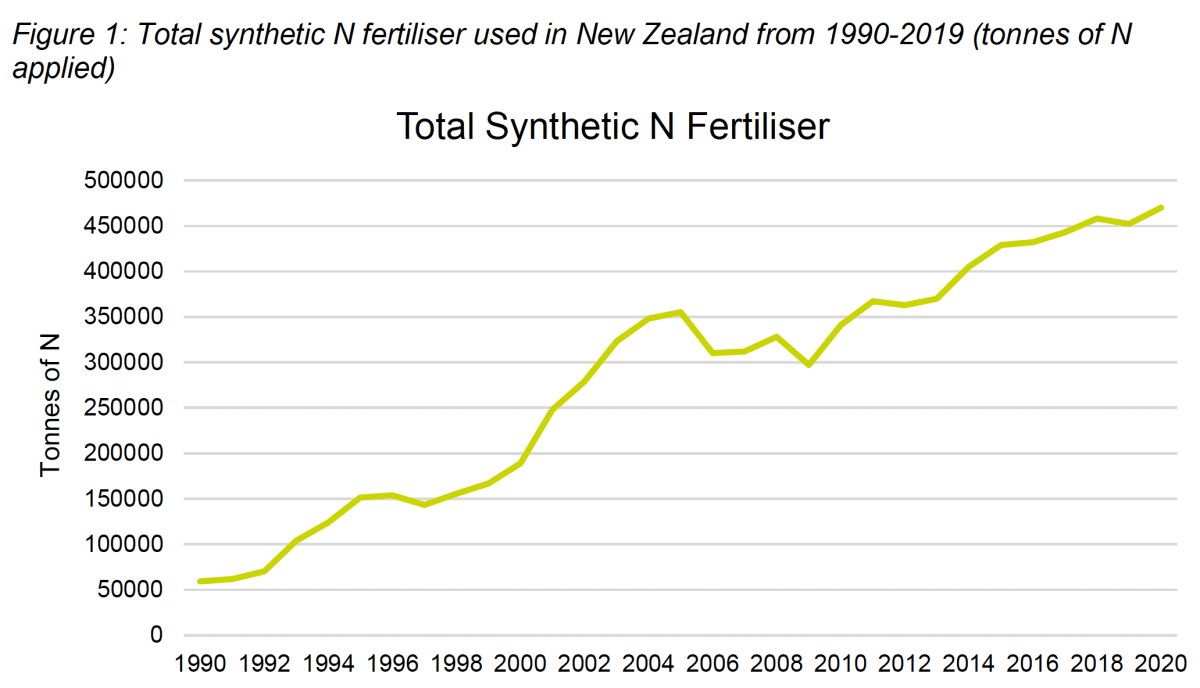

After receiving graphs from the Ministry for Primary Industries indicating a significant rise of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser usage and total emissions, the environmental group made this comparison.

Greenpeace has been campaigning for the phasing out of such fertilisers, which Rose says are the drivers of “many environmental evils”. She focuses on “industrial” dairying, which Greenpeace describes as the country’s biggest climate polluter.

Urea fertiliser is used to promote pasture growth on dairy land. This leads to more cows and therefore higher methane emissions. More water pollution, and, Potential health issuesFor some people, drinking water is not an option.

“If we turn the tap off with nitrogen fertiliser, then it opens up opportunities for premiums for organic, regenerative and organic products, but also for the use of organic waste – materials that are otherwise seen as waste and just diverted to the landfill.”

MPI estimates that only 4271 tonnes organic material will be available for food production.

Research into nitrous oxide emission research Published in the journal Nature in 2020, suggested attempts to keep global warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels might be threatened by the ongoing use of nitrogen fertilisers for food production. Clearance of land for agriculture also contributes to the biodiversity crises.

Emissions are caused by soil microbes converting fertiliser to nitrous oxide (N).2O). O.2. Three-quarters (75%) of direct emissions from synthetic fertilizers are nitrous dioxide, the rest are carbon dioxide.

Nitrous oxide is perhaps lesser known than the big two greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide and methane, but it’s a long-lived gas which is almost 300 times more potent than CO2Over 100 years. Nitrous oxide accounts for about 10% of the country’s gross greenhouse gas emissions.

Shamefully for New Zealand’s international reputation on climate change, its gross emissions have increased 26 percent since 1990. Two main reasons are increased fertiliser usage and an increase of dairy cattle. The national herd was 4.9 million in 2013.

Farmers believe that synthetic nitrogen fertilisers are a vital building block of protein and essential for the growth of grass and crops. The industry believes a ban would be economically catastrophic – and, it claims, not achieve environmental goals. This is because fertilizer emissions are dwarfed in comparison to emissions from livestock peeing or pooing. Alternatives are more expensive and less efficient, but they may be affordable enough to maintain high livestock numbers. It could also disrupt plant-based agriculture.

The country’s fertiliser industry is dominated by farmer-owned cooperatives Ravensdown and Ballance Agri-Nutrients.

They are large businesses. Ravensdown earned $52 million before tax and rebate from its continuing operations in 2021 on $712 million revenue. Ballance’s 2021 revenue before rebate was $897 million, and it made a $63.1 million profit, before tax and rebate.

However, they didn’t comment for this story. Ravensdown said the Fertiliser Association was “best-placed” to respond, while Ballance couldn’t be reached.

Similarly, Fonterra, New Zealand’s biggest company and the world’s largest dairy exporter, declined to comment. A senior communications manager said “it’s an industry matter”.

Fertiliser Association chief executive Vera Power responds “on behalf of Ravensdown and Ballance”, saying via email the cooperatives are working hard to reduce nitrous oxide emissions.

This is despite the fact that the use of synthetic fertilizers has increased 663 per cent between 1990-2019. The percentage of agricultural emissions that nitrogen fertilisers account for has increased from 0.9 percent up to 5.8% over the same time.

“The use of smart products and precision application means farmers are able to minimise nitrogen use while maintaining the enormous economic benefit it contributes to New Zealand agriculture,” Power says.

“Last year, nitrogen use actually declined as more farmers used coated products which enable them to use less nitrogen because of the increased efficiency of these new products.”

Another reason to use less is Soaring prices.

Power points: When it comes to nitrous dioxide losses and the leaching nitrates in waterways, the majority of the nitrates are leaked into the waterways from animal urine.

Dr David Burger, DairyNZ’s strategy and investment leader, says nitrogen use is decreasing with better science and improved farming practices, and there’s extensive research to find alternatives.

Farm environment plans allow farmers to reduce nitrogen fertilisers and use alternative feeds like plantain to reduce nitrogen-loss. Modern irrigation systems are another option.

However, Alarms are being raised on farm plans, and there’s is evidence, called the “efficiency paradox”This suggests that groundwater levels are lower due to more efficient irrigation and increased milking, which is leading to an increase in nitrate/nitrogen concentrations.

Burger says farm businesses must remain profitable while doing environmental work, “as that not only benefits our national economy, but local economies too”.

Increasing scrutiny of farming’s environmental impacts has piled pressure on the Government. The Climate Change Commission will later this year review progress on farm emission cuts.

Poto Williams, the Duty Minister, stated that the Government is committed to working alongside farmers to reduce greenhouse gasses.

“It’s a big challenge but many farmers are already taking action.”

Freshwater reforms are “ongoing and comprehensive”, she says. “They include introducing a limit of 190 kilograms per hectare, per year of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser on grazing land.”

It’s not far enough

Williams is not being supported by Greenpeace.

“Our argument is the [fertiliser] cap isn’t high enough,” says senior agricultural campaigner Rose. “It’s not targeting the bulk of the pollution that’s being generated by industrial dairying … the water quality or the climate issues, or the freshwater contamination.”

She says that most farmers use less than 190kg/ha. That’s backed by Fertiliser Association figures for major regions, taken over five years to 2018, showing only one province, Canterbury, has average use above 200kg/ha. Only Southland (and West Coast) have a higher average of 150kg/ha.

“It’s unlikely to make a significant difference,” Rose says.

None of the signals are strong enough, Greenpeace argues: the fertiliser cap’s too conservative, elements of the freshwater reform package These have been reducedOr delayed Concessions were madeOver strict new winter grazing regulations

The $700 million is also spent by taxpayers Clean up freshwater, including riparian and wetland planting, she says – although there are strings attached, with stricter rules.

Last November there was another blow, when the Government-primary sector partnership He Waka Eke Noa put forward draft options for pricing farm emissions that weren’t expected to reduce emissions By even 1 percent by 2030.

The draft discussions document said: “The majority of emissions reductions are expected to be achieved through recycling revenue into research and development, incentives to uptake technology, or actions on-farm that help reduce emissions.”

(Creating pricing proposals which effectively won’t shift the rudder is a head-scratching position for an organisation formed “to equip farmers and growers with the knowledge and tools they need to reduce emissions”.)

Even if the Climate Change Commission were to recommend agriculture enter the Emissions Trading Scheme – which, for the first time, would put a price on agricultural emissions, comprising almost half of New Zealand’s gross greenhouse gas emissions – Rose worries about the Subsidy levelThe Government would provide support to the industry.

“It would take 100 years for us to have agriculture fully into the ETS in a way that would be equitable to other producers and every other New Zealander.”

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern called it her generation’s nuclear-free moment, and the Government declared a climate emergency in 2020. It was criticised for having a plan to reduce lukewarm emission, and it was a It was a disappointing resultAt the UN climate conference in Glasgow (also known as COP26).

What’s needed from the Government is “more substance and less stardust” on climate, Rose says – and that includes addressing the elephant in the room, agriculture.