[ad_1]

Rising energy prices are particularly detrimental to low-income households. A new report compares Australian and EU approaches to energy affordability.

Some are concerned that higher electricity prices will be a result of the transition towards clean energy. High prices can lead to energy insecurity: When a household cannot afford the essential services such as heating and electricity, it can cause energy poverty.

Our new reportThe publication, which was released today, compares approaches for energy affordability in Australia and the EU.

The EU is currently experiencing an energy price spikebecause of increased demand due to the post-COVID economy recovery and Russia’s gas supply limitations. In Australia, wholesale electricity prices reached unprecedented levels in 2018, although they’ve since declined.

We found that Australia can learn a lot about how to put in place policies to alleviate energy poverty from the EU. We also show that electricity prices can be kept under control if the market and regulatory frameworks are right. This is because the electricity sector is decarbonizing.

Are apples and oranges the same thing?

Why would you compare Australia with a large population union of member countries? Australia and the EU share many similarities in relation to the energy sector. For example, Australia has a large grid that crosses jurisdictions. They also have shared governance arrangements.

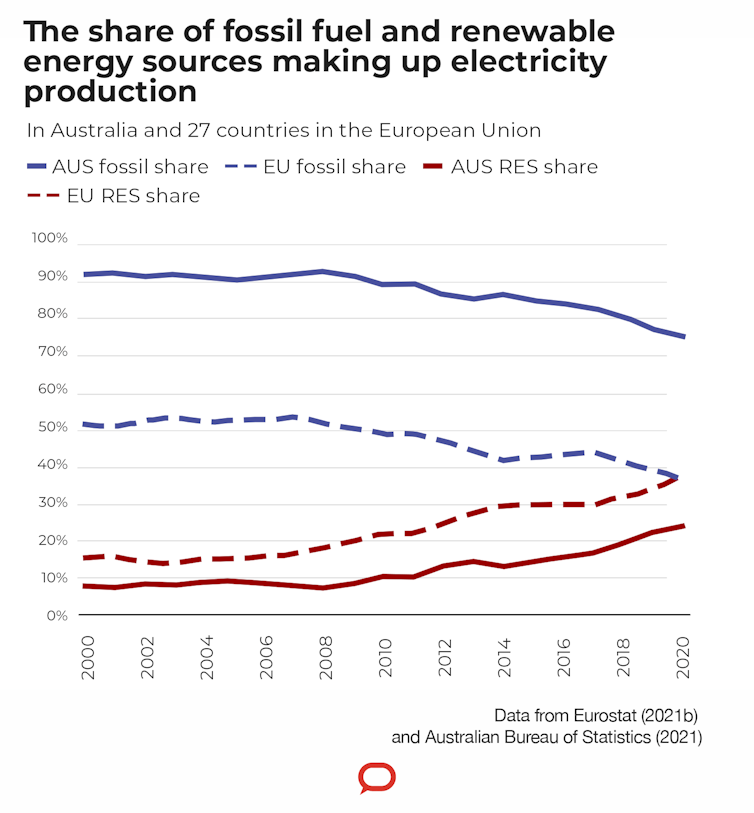

Both countries are experiencing an influx in renewable energy supply. However, this has been more policy-driven than in Australia. And EU member states, like Australia’s states and territories, are ultimately responsible for energy regulation within their boundaries.

Also, coordination is important. GovernanceEnergy requires agreement between jurisdictions.

Australia’s approach to energy affordability is more coordinated and top-down in the EU. There are many lessons that we can learn from the EU. However, there are not cut-and-paste solutions.

What’s driving the cost of electricity?

Well, it’s complex. Both wholesale and retail electricity prices have been moderated by the introduction of low-cost renewable supplies over the past decade. EuropeAnd Australia. This trend is expected to continue in the near- and mid-term.

Adding more renewable energy into the grid, however, requires upgrades to the poles and wires that carry the electricity – and this is costly. What’s more, low wholesale prices will encourage the early exit of ageing coal plants, which needs to be managed to avoid price shocks.

Australia can learn from the EU in this regard, where almost all member states – such as France and Germany – have announced PlansTo phase-out coal. They often set the requirements and establish closure dates.

This isn’t yet the norm in Australia, as most recently seen with Origin Energy’s surprise decision to bring forward the Closure of Eraring – Australia’s largest coal plant – last week.

The interconnection between Australian states is less than that of most EU regions. Start to make a difference). This means that shocks, such early plant closures are more difficultly absorbed in Australia.

Both Australia and the EU are trying their best to find a fair and efficient way to distribute the costs of network upgrade costs across society. This is also true for Germany, where electricity stakeholders have to pay. are discussingHow to distribute grid costs evenly across the country and not overload regions with higher renewable power.

If the upgrades are funded by greater use of grid resources, such as heat pumps or electric vehicles, it spreads out the costs over a larger base.

Energy poverty in Australia

The most important indicator of energy inequality is the ability to determine which households are spending the most energy. Justice. There are many differences between Australia, Europe, and the United States.

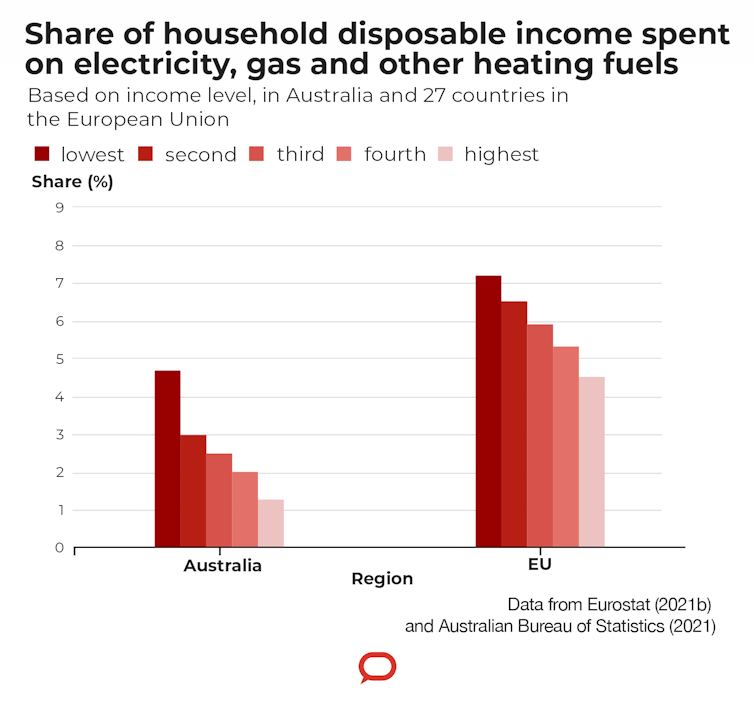

In Australia, as seen in the graph below, the average household spends a lot less on electricity and heat (2 per cent of a household’s disposable income) than their EU counterpart (6 per cent).

In Australia and the EU, lower income households spend a larger percentage of their income on electricity and heating while consuming less absolute terms.

However, dispersion is much more evident in Australia where it has been IncreasedThe last ten years have been a challenging decade. This means that low income households are disproportionately affected when energy prices rise. It is imperative to make concerted efforts to address this issue.

Policies to address energy poverty

It is essential to eliminate energy poverty. Politique issueThe European Commission has made it a key part of the EU’s aforementioned activities. Fair energy transition.

There are many regulations and institutions. This section is dedicated toIt will be addressed. The European Commission’s “Renovation wave” policy, for example, is a large-scale renovation plan that focuses on low-income and social housing. This provides long-term assistance to vulnerable households at a scale never before seen in Australia.

The EU provides its member states with clear information. GuidanceHow to measure and address energy poverty. Instead of focusing on a single metric, multiple and composite measures are used. This includes absolute energy expenditure, owed utility bill payments, and self-reported inability keep the home warm.

The EU also has resources for institutions such as the Energy Poverty ObservatoryThe new Energy Poverty Advisory HubTo better understand the causes of energy poverty, click here

However, the EU ambitions are not being translated to member states in a uniform way. Bulgaria is performing worse than Spain, for instance. The severity of the problem doesn’t necessarily translate into national-scale policy efforts.

In Australia, there’s no national overarching framework for the energy transition that includes principles on equity and leaving no one behind.

Australia has the National Electricity ObjectivesThese are the guidelines for market planning. These, however, don’t reference equity or decarbonisation. Energy poverty is still a vague concept. There are no clear goals, targets, metrics, or metrics to collect data, and no institutions to monitor it and report on it.

Energy “hardship” or “stress” are more common terms, and Australia has a well-established Consumer protection framework. This is more about reducing costs by offering concessions, retailer responsibilities and protection against possible disconnections of electricity.

Whatever the language used, Australia can learn from Europe’s experience of developing a coherent definition, criteria for measurement, and independent institutions to report on energy hardship.

Australia’s rapid rollout of the internet has also provided lessons for Europe. rooftop solarSmart metres.

Australia is a leader in consumer protection by its rapid rollout. This includes addressing inequitable cost distributions and barriers to market participation. Rule changes are also being made to address new responsibilities for providers in a changing energy landscape.

There are many examples of industry-driven efforts to promote cultural change in Australia regarding affordability. The example of the Energy CharterNational CEO-led collaboration that is committed to customer-focused principles, including energy affordability.

This can be very effective and lasts if there is strong community involvement and buy-in from big and small firms.

![]()

About the authors Sangeetha ChandrashekeranSenior research fellow at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Children and Families Over the Life Course The University of Melbourne; David Ritter is a senior researcher at Oeko-Institut; Dylan McConnellResearch fellow at the Australian German Climate and Energy College. The University of Melbourne; Johanna Cludius is a senior researcher at Oeko-Institut; and Viktoria NokaA research assistant is Oeko-Institut.

This article has been republished from The Conversationunder Creative Commons license Read the Original article.

[ad_2]