Pork producers love the smell of money. Long time calledThe stench of pig waste in the air in eastern North Carolina is so revolting that it can be detected everywhere. In this area, hogs outnumber humans by as much as 80%. 35To 1. For many Black, Latinx, Indigenous residents who live close to the giant pig farms of the state, the smell is associated with nausea and anxiety, breathing problems, and racial prejudice.

In eastern North Carolina, industrial pork production exploded between the 1980s and 1990s. as mega facilitiesSmall farms were displaced by thousands of animals in each house. Residents have been fighting for clean air, clean water and a life without the stench of the since then. 10 billion gallons wasteThe states 8.8 Million PigsProduce every year.

The US Environmental Protection Agency, (EPA) was inaugurated in January. An investigation was launchedAn NGO representing multiple community groups filed a discrimination case against the state. The inquiry aims to determine whether or not the state environmental department discriminated racially against residents when it allowed several hog farm farms to use their waste to make fuel.

The EPAs probe is just the latest in a long battle in North Carolina against what residents who have been affected by pollution from factory farms claim is a form environmental racism. This term is used to describe the disproportionate effects of pollution, whether from the environment or from the farm. Agricultureurban power plants in communities of color.

This fight is not easy. Big Meat reigns supreme in the state’s culture, politics, economy, and politics. North Carolina ranked #5 in 2020. SecondThere are several states that produce pork. DritteTurkey production includes: FourthIt is used in chicken production. It supplies the US as well as the rest of world with 25 percent of the pork that is exported to the USA. China, Mexico Japan Korea, Korea, and Other Countries. But, pork and Poultry productionIts environmental impact on the environment Highly concentratedIn poverty-stricken countries with high Black, Latinx and Indigenous populations.

This is my home, and I love this, Carl Lewis, a Black barber, in Bladen County North Carolina, said to me in an interview The Smell Of Money, A documentary I am making on the subject. Lewis’ barbershop is located near a sprayfield and hog farm, where hog manure is released into the atmosphere over cropland by a machine that looks almost like a giant sprinkler. But there’s a hog farm there, he said, pointing to the 12 metal buildings, three waste lagoons, and a patch of pine tree behind. There are flies everywhere, smells, trucks, and noise. It is really annoying. It’s not like people have moved. Most of us are poor and cannot afford to move.

Lewiss communities have seen their impact. Well documented since the 1990sInclude everything Poisoned wellsAnd Property values are decliningTo shorter lifespans and higher rates of mortality PhysicalAnd Mental healthResidents facing problems

Courtney Woods, an associate Professor at the University of North Carolina School of Public Health who has studied these effects, describes one of the most disturbing stories they have heard. They see it on their cars, in their homes, and they feel outraged. There are associations that stress and anxiety have. studies to demonstrate.

Massive Covid-19 outbreaks at meatpacking plants in spring 2020 brought to light the daily dangers associated with the killing and chopping of hundreds to thousands of animals every day: cuts, amputations and chemical exposure. These hazards are carried by a majority of Black, Latinx, or immigrant workforce.

However, as North Carolina’s case shows, the harm that the meat industry does to vulnerable communities goes well beyond the slaughter plant. You can see how the supply chain impacts the poor communities of color, which clearly pay the price for cheap chicken and bacon.

How factory farms pollute water and air (and how they get away avec it)

Thought The climate crisis is caused by meatsis becoming more prominent, factory farm pollution is receiving comparatively little attention. Despite the fact that 12700 premature deaths are caused each year by air pollution from animal agriculture, which is more than the deaths caused by coal-fired power plant pollution, one study shows Recent studies.

Factory farms or concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) waste is usually stored in huge, open-air pits and mounds. After that, it is sprayed on the ground or spread over the cropland as fertilizer. These systems are supposed to recycle nutrients in the waste, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, back into crops. In practice, however, urine and feces from animals are often used. Make their way to the farmAnd In the surrounding environment.

Poultry waste is a dry litter made from chicken waste. It looks like wood shavings with blood, excrement, feathers and feed. It is usually stored in a plastic bag. big piles outdoors, can be washed away by the rain or blow off in the wind. Pig waste pits are often found LeakageOr OverflowEspecially during strong storms and North Carolina’s intense hurricane seasons.

Pollution can cause algal blooms, an overgrowth of algae which can produce toxins and decrease oxygen levels in waterways. massive fish kills. Groundwater contamination is especially problematic in rural areas. Residents drink water wellAccessing county lines could provide untainted water costs that money people often don’t have.

We had wells, but they were not enough. [were]Delores Miller, a resident of Duplin County, North Carolina, said that the water was contaminated by the hog farm. She lives only a few hundred feet away from a hog CAFO lagoon in Duplin County. The smell is so strong that you can’t hang your clothes up, you can’t do anything in the yard, and the yellow flies are also a problem.

Children who attend North Carolina’s CAFO schools have an unforgettable experience. Wheezing and asthma at higher levelsComparable to those who attend schools closer to CAFOs, and residents living within one-and-a-half miles of CAFOs. High blood pressure; Eye, nose, and throat irritation; difficulty in breathing; nausea; and tightness in the chestProblems that get worse as the odor gets worse are called a “smell problem”. One StudyIt was found that Eastern North Carolina residents who live near factories have higher rates for asthma, anemia and kidney disease than those who live in rural areas. This includes controlling for poverty.

Although the environmental and social harms caused by CAFOs date back decades, there is little relief in existing anti-pollution laws. The federal Clean Water Act mandates that the EPA hold factory farm owners accountable. However, the agency primarily RegulationsOnly the Largest CAFOs(For hog farms, this refers to CAFOs that have more than 2,500 pigs more than 55 pounds or more than 10,000 pigs less than 55 pounds. The EPA Factory farms can useThe problem-prone waste disposal and storage practices discussed above are It doesn’t have toCAFOs are monitored for the presence of pollutants in waterways.

The EPA also leaves a large amount of enforcement for regulations on the books to state government. However, state agencies often lack the political will or resources to monitor water pollution. Never give upAny real force can be used against violators.

CAFOs are also a major source of air pollution. In 2005, the EPA entered into what environmentalists call a “agreement” to regulate this issue. sweetheart dealWith thousands of CAFOs, the EPA agreed not to enforce regulations on air pollution as long as the meat sector paid for a study. The EPA intended to use the data to analyze the industry’s role in air polluting. then begin enforcement. It hasn’t even been implemented nearly two decades later.

Advocates for environmental justice say that tight ties between the industry sector and legislators hinder progress. Naema Mohammed, senior adviser for North Carolina Environmental Justice Network, said that legislators are so deep in the pockets these dirty industries, they can’t escape.

Since 2000, meat companies and meat trade groups have contributed more than $2.5 billion to the meat sector. $5.6 MillionNorth Carolina candidates The LargestThe North Carolina Pork Council, North Carolina Farm Bureau and Smithfield Foods are some of the donors. Smithfield Foods is owned by the Chinese conglomerate WH Group. Numerous Legislators Are CurrentOr, you could say the former FarmersThey have helped to pass pro industry legislation and defended the sector in the press.

Jimmy Dixon (R), a former poultry farmer who is now a North Carolina state representative, represents the region with the highest concentration of CAFOs in the United States. Bill championedThis law was created to prevent citizens from suing large meat companies for pollution. Led pro-industry rallies, and has DiscontinuedResidents view residents’ concerns about the stench, nuisance, and living near a CAFO for Hogs as exaggerations. They accuse them of being recruited to be greedy lawyers.

North Carolina hog country: The fight for environmental justice

North Carolina’s pro industry, hands-off regulatory climate is inseparable form its state history. Many North Carolinians are unable to access the political and economic power required to stop factory farms moving into their communities and to get relief from the pollution caused by the legacies of slavery and genocide, as well as land theft and racial discrimination.

One historical anecdote shows how race played a major role in North Carolina’s history of the pork industry. Residents, including many Black, Latinx and Indigenous people, have been calling for stricter regulation for years. However, a moratorium was passed on new hog CAFOs in 1997 after a state representative. HearOne was to be built near a wealthy white community and a golf resort in the district.

Existing CAFOs were grandfathered into law, and factory farms are still more common in low-income communities and communities that are diverse. There are factory farms in some parts of North Carolina. 10 timesThere are more CAFOs in poorer and non-white neighborhoods than in wealthier, more whiter areas, even after controlling for population density.

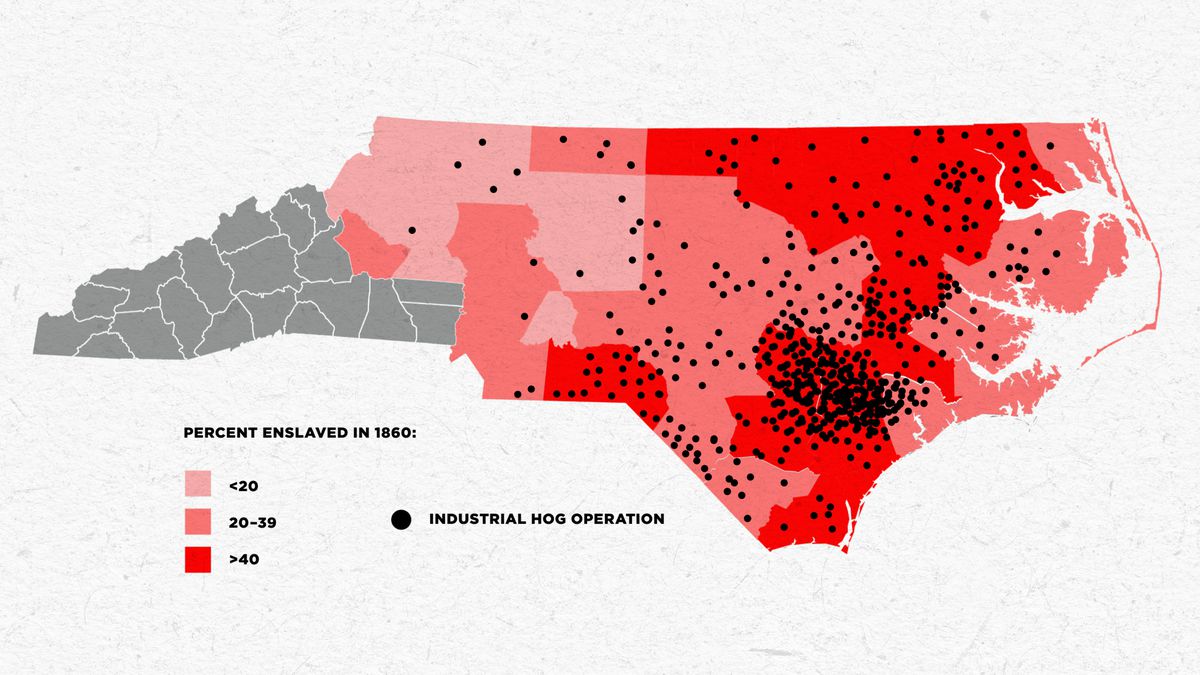

Public health researchers and community groups are the first to take action Environmental racism is a term that has been used.In 1996, they discovered an astonishing correlation between the Black Belt and where previously enslaved persons had settled. North Carolina’s modern-day distribution of hog caFOs. Residents who knew from childhood that these polluting facilities were distributed was not accidental, stuck with the name.

Elsie Herring was a vocal opponent of the pork industry. The symbolAfter a hog farm moved onto her land in the 1980s, she was often referred to as a fighter for basic civil and human rights. (She died last May from a type of cancer that she was not sure about. linkedTo reduce air pollution.

She said that I believe that environmental racism is a major part of the picture of what’s happening with the pork industry. If they are not there, why not put them right next to their homes? While poverty is a factor, there are plenty of poor white people living in the same area.

Muhammad claims that Eastern North Carolina has become the North Carolina’s dumping grounds. We always say that if you don’t want something in your backyard, come to eastern North Carolina. We will show it to ya, because it is here.

Residents like Herring have been fighting a multi-front war for the past 30 years, with the support of a wide coalition of legal and environmental advocacy groups, civil rights advocates, and public health researchers. They’ve done creative things like bringing gallons hog feces to Governors Mansion and setting up mock hog farms with manure sprayers at the state capitol grounds. They have petitioned the industry, attended council meetings, and lobbyed legislators. Testified before Congress, and even Run for officeAgainst pro-industry politicians

They have also filed federal Civil Rights Act complaints with the EPA alleging North Carolina’s environmental regulatory body discriminates against communities and color by allowing CAFOs to pollute their drinking water. (Under Civil Rights Act, no entity receiving federal funding may discriminate based on race).

The most recent ReportedThe January filing argued that regulators discriminate against communities of color by allowing certain CAFOs to turn animal waste into fuel. This is a practice environmental justice advocates call discriminatory. worsens pollutionby enforcing existing systems and exposing communities to new gas pipelines, plants, and other means.

North Carolina residents have longed for relief for years by suing the industry. However, Big Meat is not cheap or easy to sue. Financial barriers intimidationThe industry directed at both lawyers and would-be plaintiffs made this tactic impossible until residents finally found Mona Lisa Wallace. She was a brave lawyer from a small North Carolina village who was willing to take on the meat industry goliath.

Wallaces firm filed 26 nuisance suits on behalf of nearly 500 North Carolina residents. These lawsuits were brought by almost all people of colour against Murphy-Brown pork producer. Later, Murphy-Brown became a subsidiary company of Smithfield Foods. Smithfield Foods is the world’s largest pork producer. The suits described how noise, smell, and health problems resulting from air and water contamination made plaintiffs’ properties and land less livable. The lawsuits did not name the farmers as the plaintiffs and their lawyers believed farmers were also victims of corporate agricultures exploitation.

Five of the lawsuits were tried and five were thrown out. Jurors sided with residents in each case. The juries awarded $549,902,400 to residents. This amount was reduced to $978,880,000 because of a state cap for punitive damages. Industry-friendly legislators.

Smithfield appealed. However, the federal appels court sided with Smithfield, forcing Smithfield and other plaintiffs to settle all remaining cases. Smithfield has not made any statements regarding the settlement’s terms or amounts.

Ren Miller, plaintiff, said that conditions have not changed for her or her family since the settlement announcement. She said that it made her feel good to have won. They will continue spraying even though they won’t stop because of that win. [hog manure]on my house. It is still going on. I don’t go outside my front door. I stay inside the house and keep the windows closed. I still smell it. Miller said she will use the settlement money to pay her medical bills.

In a StatementKeira Lombardo, Smithfield spokeswoman, stated that the company settled. The civil actions brought in North Carolina were part of a coordinated effort made by plaintiffs lawyers and their allies to dismantle our safe, reliable, modern system of food production. We pledged from the beginning to vigorously defend agriculture in North Carolina and protect North Carolina’s farmers from this assault. This decision is not the end of our support for America’s farmers.

Despite the victory in the courts, North Carolina’s legislature passed two laws despite the ongoing lawsuits. Retaliatory billsThis was done to slow down the movement against CAFO pollution. It is unacceptable. Wallace says that I find it unconstitutional. I find it sad that anyone would vote in favor of a bill that treats people differently and makes certain peoples homes more important than others just to protect the industry.

Every state had a constitution before the North Carolina case. Right to Farmlaw that protects agribusiness from similar lawsuits to a certain extent. Big Meat was so scared by its losses in North Carolina, it has since filed for bankruptcy. lobbiedTo strengthen these laws, legislatures are needed in several ag-heavy countries.

Today, poor communities of color in the state as well as elsewhere continue to suffer from pollution. Advocates say policy reform is what is needed.

Tarah Sheinzen, legal director of environmental nonprofit Food and Water Watch, said that the EPA could do a lot to hold CAFOs responsible for water and air pollution. Heinzen claims that the EPA’s powers under the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act as well as transparency laws remain largely untapped when dealing with CAFOs.

A spokesperson for the EPA told me via email that they are working towards a comprehensive strategy to address CAFO-related air emissions. They have also been developing improved emission-estimating methods. [and]Obtaining additional information on the extent of CAFO emissions and the control options. It plans to release draft reports by the end of this summer.

The spokesperson also mentioned that the EPA was currently evaluating different Clean Air Act regulatory tools to address air pollution. It is also working to correct injustices wrought through past policies through active involvement with underserved communities and regional partners. Virtual workshopsas well as funding air monitoring.

Congress also hamstrings the EPA. Congress’ annual spending bill, which funds the government, has always included provisions that have been in place for years. Block the EPAMonitoring and regulating CAFO greenhousegas emissions and manure management systems. These provisions were included in President Joe Biden’s March spending bill.

The White House announced in February that it would be launching a New screening toolIt will identify communities that have been harmed by polluting, but it won’t include race, which disappointed environmental justice advocates. The White House claimed that the decision was made to avoid legal challenges and that it was being challenged by the Supreme Court.

Herring shared with me her thoughts about this year, a year before her death, that I will not be happy until the industry makes significant changes to ensure that no one lives in such conditions. All of these are worthy causes. We need young people to fight environmental racism, injustices, and to make this a better world for their children. When we leave, this world will be theirs.

Jamie Berger is the writer and producer of the feature-length documentary. The Smell Of Money. She was born in North Carolina and is now the chief of staff at Mercy For Animals.