[ad_1]

Forget about the warm ocean breeze and palm trees. The Upper Midwest could soon become the most desired living destination in America.

The Great Lakes region has the appeal of being a safe place to ride out any future wild weather. It’s far from the storm-battered Eastern seaboard and buffered from the West’s wildfires and drought, with some of the largest sources of fresh water in the world. The Great Lakes cool summer and temper winter’s bitter winds. The rising temperatures are starting to reduce the winter weather bite. Michigan, in fact is. turning into wine countryYou will find vineyards that grow warm weather grapes like pinot Noir and cabernet Sauvignon.

Long-simmering speculations about where to hide from climate change picked up in February 2019 when the mayor of Buffalo, New York, declared that the city on Lake Erie’s eastern edge would one day become a “climate refuge.” Two months later, a New York Times article made the case that Duluth, MinnesotaLocated on the western side of Lake Superior,, it could be a great place to call home for Floridians or Texans who are looking to escape the scorching heat.

“In this century, climate migration will be larger, and is already by some measures larger, than political or economic migration,” Parag Khanna, a global strategy advisor, told me over the phone. His book, Move: The Forces are Uprooting Us, analyzes where people are relocating to and how the “map of humanity” will shift in the coming decades, with an eye toward climate change, politics, jobs, and technology. Khanna is especially bullish about Michigan. When I mentioned I grew up in northern Indiana a couple of miles south of the Michigan border, he said, “Go back and buy property now. At least, that’s the way some people are interpreting it.”

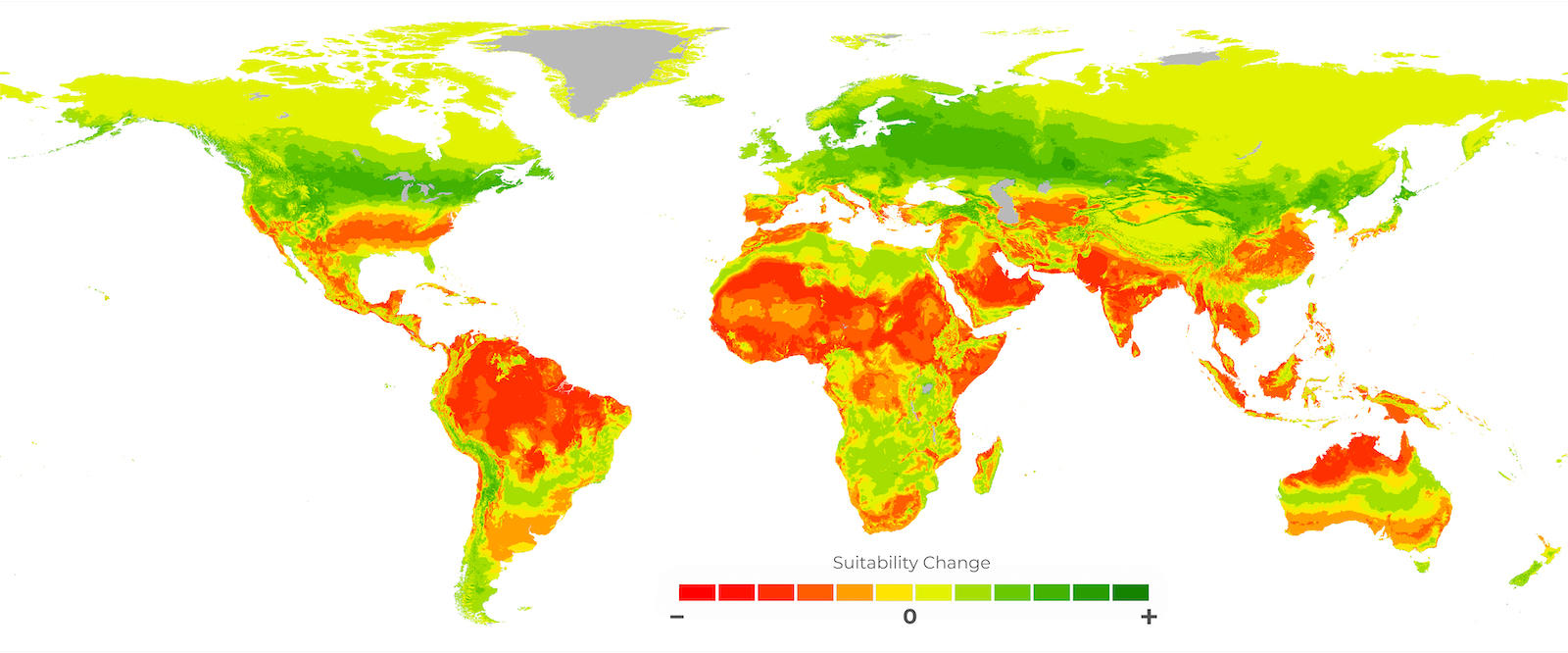

There’s a big market for mapping out where people will live in a hotter climate, with the consensus landing mostly on northern latitudes buffered from rising seas, heat, and drought. These forecasts are already being realized, with Great Lakes communities planning for an influx from rich preppers and residents. buying bunkers in New ZealandYou can ride out the apocalypse. Vivek Sharada, who studies climate change at Portland State University, said that he is frequently contacted by real estate investors to ask where to buy property.

NASA, National Academy of Sciences. Chi Xu and Marten Scheffer

Khanna claims that Americans are moving more for work and housing affordability than they are because of climate change. However, migration from drought, wildfires and hurricanes is already underway. “The global answer is, it’s already happening, right?” Khanna said. “In America, you’re only seeing early signs of it.” Around 25,000 migrants fleeing Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria in 2017 settled in Orlando, Florida, and as many as 5,000 moved to the proclaimed “climate haven” of Buffalo. Many of the thousands who fled Paradise in California’s 2018 Camp Fire have relocated to Chico.

Recent headlines predict that the state of Michigan will be “the best place to live by 2050” and that cities in upstate New York will be among the “the best ‘climate havens’” in the world. In October, a local paper in Minnesota declared that “climate-proof Duluth” was already attracting migrants from the smoke-filled, wildfire-ridden West.

With as many as 143 million people worldwide expected to be on the move because of climate change by 2050, would-be havens are sure to face new challenges — gentrification, housing shortages, and issues scaling up services quickly. However, planning ahead can ease the stress on both cities and newcomers. These climate havens can be transformed into a welcoming refuge for all by seeking expert advice.

Step 1: Figure out what a ‘climate haven’ really is

Even in a so-called safe haven, there is no escape to the effects of an overheating world. Heavy flooding is currently taking place in the Great Lakes Region: 11,000 people live in central Michigan evacuatedLast year, heavy rains overwhelmed dams. Wildfire smoke from Canada blew into Minnesota this summer, bringing with it a lot of wildfire smoke. an unprecedented hazeIt is dangerous to breathe.

So defining what makes a city a “refuge” isn’t simple. A recent study by researchers at MIT and the National League of Cities attempted to lay out the qualities of “climate destinations” like Duluth, Buffalo, and Cincinnati, Ohio. First, the effects of climate change should be considered “more manageable” than other places — in other words, not subject to monster hurricanes, fast-moving wildfires, and the unabated rise of sea levels. Havens should have access to fresh water and affordable housing as well as infrastructure to support many thousand of new residents.

The final qualifications are a bit squishier: These cities must express a “desire to grow and be welcoming” and work on becoming sustainable and resilient. The study points to Duluth investing $200 million over recent years into improving its shoreline protections and wastewater system, and Cincinnati’s plans to cut carbon emissions and host climate migrants (prompted in part by a wave of former New Orleans residents that moved to the city after Hurricane Katrina in 2005).

Gregory Shamus/Getty Images

Nicholas Rajkovich, a professor studying resilience and urban planning at the University at Buffalo, says he wants more concrete action behind Buffalo’s “climate haven” promises. “In some cases, it’s become more of an economic development slogan than the real detailed and robust planning that is going to be necessary to actually make these places a haven from climate change,” Rajkovich said.

Step 2: Make people first

Cities that seek to attract climate migrants stress the benefits that come with them, such as economic growth and the ability to attract skilled workers. But it’s important to remember that “migrants are not a tool to an end” and that they get the support they need, said Susan Ekoh, an adaptation fellow at the America Society of Adaptation Professionals, an organization preparing towns in the Great Lakes for the expected waves of future inhabitants.

Some residents in self-declared climate havens don’t want the title. Ekoh met with representatives from tribal groups around the region, as well as local and state officials. Ekoh is often concerned about gentrification. This is when wealthy people will move into the area, driving up housing prices and displacing poorer residents. Another critique is that climate “refuges” are failing to protect the people that already live there. For all the talk of Michigan being surrounded by ample freshwater, it’s also known for lead-poisoned water in cities like Benton Harbor.

Professor Shandas from Portland State said that cities should have housing policies that can prevent gentrification and prepare for a backlash. Idaho, for example, has seen an influx California expats looking for affordable housing after the drought and fires of California. One researcher stated that there has been an influx of Californian expats to Idaho, fleeing fires and droughts. They are looking for somewhere more affordable. Politico that some locals, conservatives and liberals alike, resent the newcomers, painting things like “California sucks” on highway overpasses.

“That’s the kind of stuff I worry about,” Shandas said. “We can build the schools, we can build the housing, but is that local community ready for big shifts of people moving into the location, and potentially people who are very different from them?”

Step 3: Make smart decisions

Next is to make the city attractive while reducing emissions, using resource wisely, and keeping climate change at bay.

There are many ways to cut a city’s carbon output, like building dense housing, improving public transit, and cleaning up the electric grid. “You’d want to build in such a way where you have a lot of access to renewable and decentralized power,” Shandas said. But what do you? don’tBuild is equally important. Constructing a new “green” building still leads to a lot of carbon emissionsRetrofitting existing buildings is often less expensive and more wasteful.

The Midwest is already vulnerable to flooding. Climate change is expected to make things worse. Building in floodplains is not a good idea, nor is covering everything with impermeable asphalt. Cities should also find ways to beat the heat — parks keep things cool, while highways make it hot. City planners should not be surprised by this. “I mean, it’s not rocket science,” Shandas said. “We’ve been doing this for a while.”

Shandas said he’s heard people in Midwest cities get pretty excited about their future. “I was in a couple of meetings with a group of folks in the Great Lakes, and they were just like, ‘We are the climate haven — we are going to be the best place in the country and people are gonna flock to us,’” he said. While that kind of enthusiasm is “fantastic,” Shandas said, if cities don’t start preparing for the actual reality of thousands of people moving in, “it’s going to be a hard sell.”

[ad_2]