The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident that left radioactive waste in Europe, some of which is still present 35 years later, prompted a reevaluation on the cross-border effects of nuclear energy. Some plant projects were abandoned in border areas, while existing reactors were subjected more stringent safety rules.

Twenty-five year later, the aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear catastrophe prompted Germany and other countries to commit to eliminating atomic fuel by 2022. Belgium also just confirmed it will be nuclear-free by 2025.

However, a decade after Japan’s tsunami-induced meltdown in which nearly all of the country’s population was killed, countries from China to France to the United States still depend on nuclear reactors for their power. Many of these reactors were built in the 1960s and 1970s.

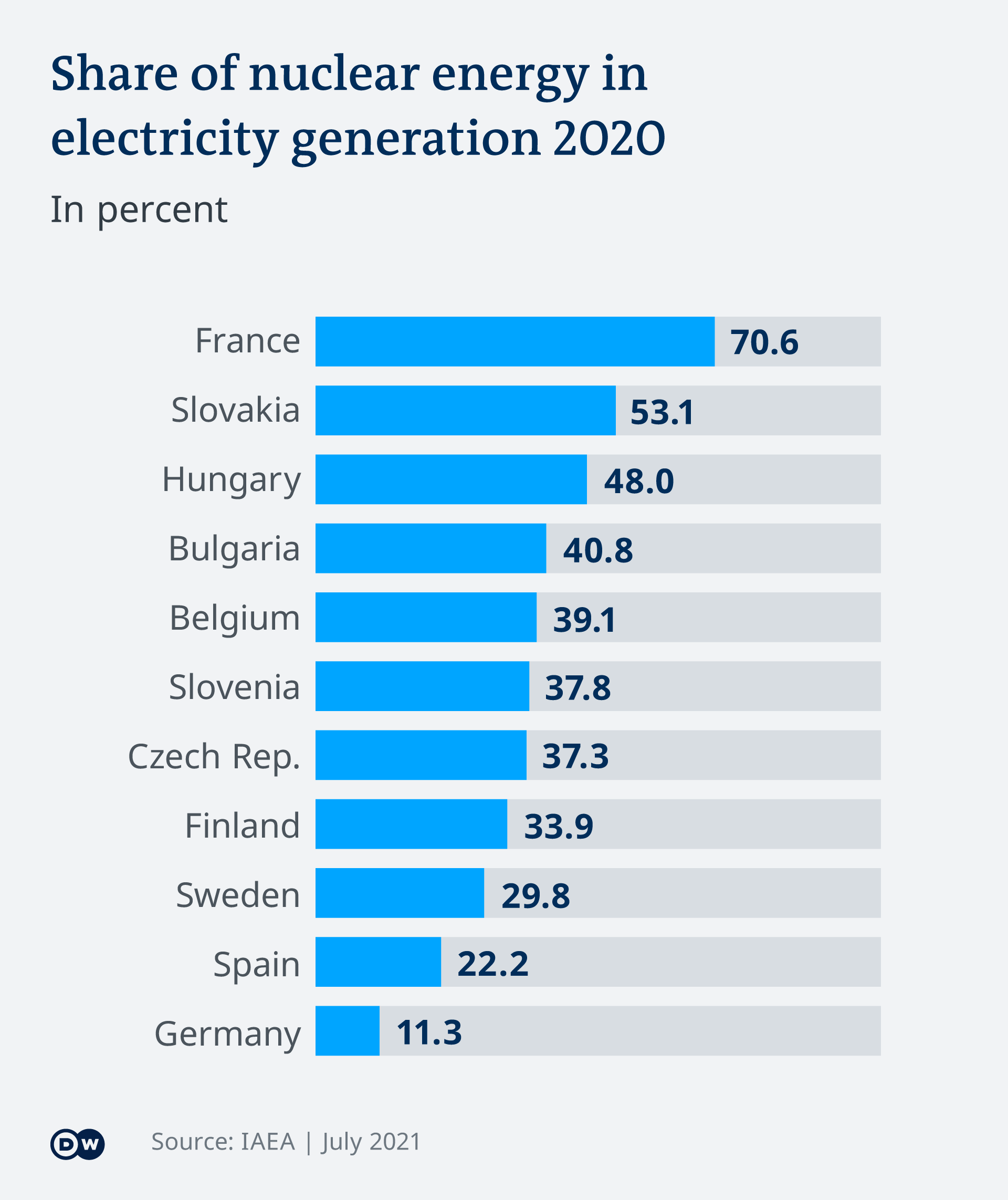

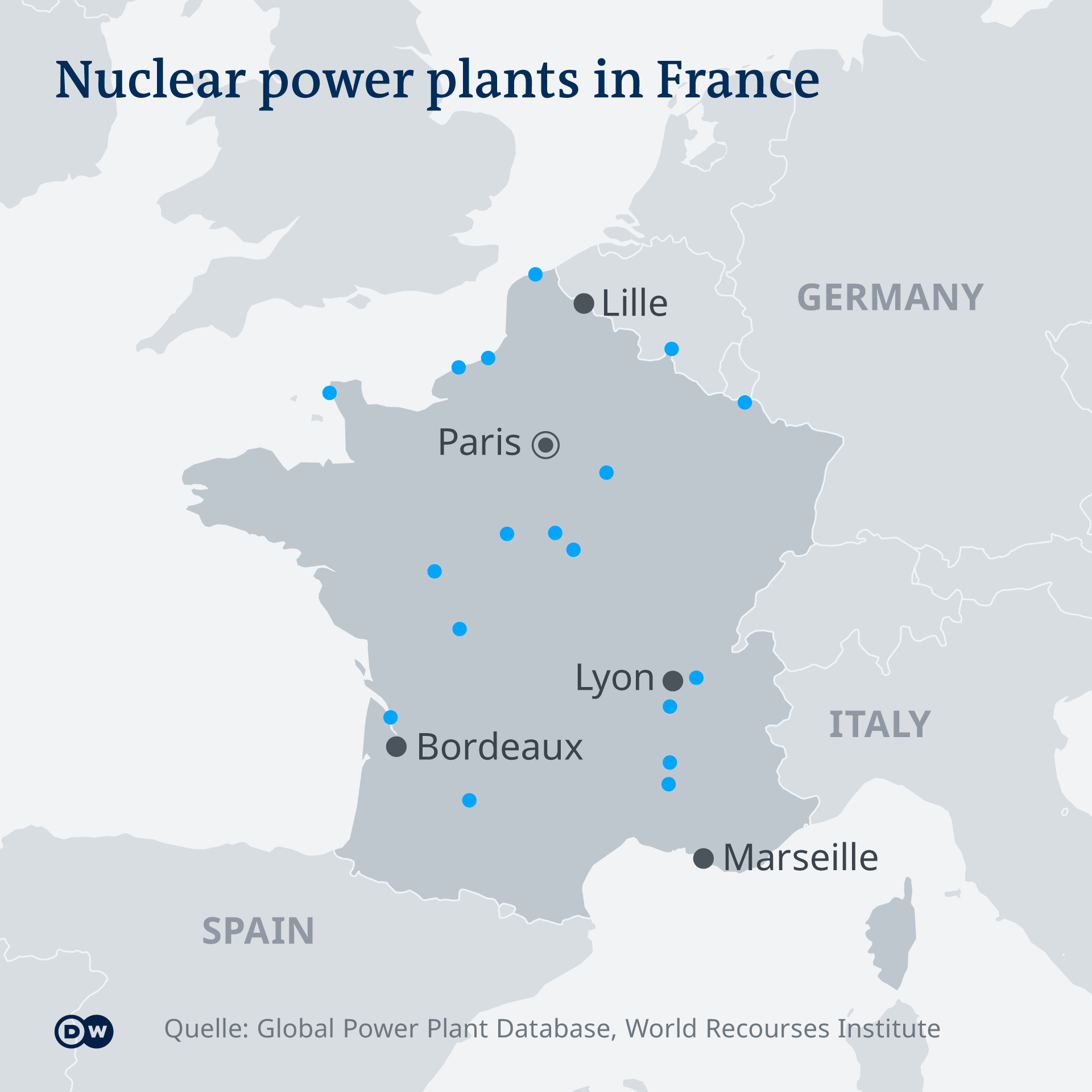

France, which generates 70% of its electricity with atomic power, is the world’s most dependent country on nuclear energy. Last FebruaryIt would prolong the life of its 32 oldest reactors by an additional 10 years.

Some are questioning whether such nations still have the right, partly because of the increased safety risks associated with ageing facilities.

France closed a reactor at its oldest nuclear facility at Fessenheim, near the German border in February 2020 due to cracks in the reactor cover. The German Environment Minister Svenja Schulze confirmed Germany’s desire to influence nuclear policy across Rhine.

“We won’t stop our efforts to promote a move away nuclear power in our neighbouring countries.” She said, This is an additional feature The “Nuclear Phaseout in Germany is rock-solid”

Who has the power of deciding on nuclear?

Though a raft of treaties and agreements lay out minimum consultation requirements between states, there is no framework to specifically consult with local communities across borders that could be most affected by a nuclear accident, noted Behnam Taebi, co-editor of The Ethics of Nuclear Power and professor of energy and climate ethics at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

The 1991 Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context obliges contracting parties to prevent, reduce and control “adverse” impacts across borders, while the 1998 Convention at Aarhus applies Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration that states “environmental matters are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens.”

According to Taebi these conventions deal with transferring risks between states. They don’t say anything about local communities at borders of neighboring countries, or how they should consult. There is no binding transboundary procedure relating to nuclear energy development, and no framework in place that could, for instance, force France to communicate and consult with towns and cities across the border.

The International Atomic Energy Agency does have guidelines focused on national nuclear energy regulators, Taebi said, however “strictly speaking it’s up to each nation itself on how to decide to move forward.”

Stefan Kirchner is a research professor of Arctic Law at the University of Lapland, Finland. These treaties provide a platform for cross-border consultation.

He said that cooperation works reasonably well in principle, especially in Europe, where countries often share multiple borders.

In a statement to DW, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) said global energy authorities, including the World Association of Nuclear Operators, have, in the last decade, created a much higher level of “joint action to assure nuclear safety than ever in the past.”

“A common understanding and practice across the globe” [has]”All countries have been able to ensure high levels of nuclear safety at operating plants, even those considered for long term operation,” the NEA said.

But in 2018, referring to Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium, the Dutch Safety Board which independently investigates the causes of incidents or accidents concluded that cross-border “cooperation has partly been arranged on paper, but that it probably will not run smoothly if a nuclear accident were to occur in reality.”

For 10 years, Austria opposed the Czech Republic’s Temelin nuclear plant that opened in 2000 near its border, with some politicians threateningTo block Czech entry into EU until the latter agreed on tightened safety precautions.

While the European Commission stepped in to help resolve that conflict, Kirchner noted that under current agreements, neighboring countries have no power to veto unwanted developments.

Transboundary decision-making is limited

According to Behnam Taebi, cross-border consultation is too often limited to national governments because states, rather than communities, are parties of existing conventions.

He stated that he was concerned about the inability to involve local communities in decision-making. “The least that we could do is engage with other authorities across border, as well as communities, regarding emergency responses. If anything goes wrong, this is going to be crucial.

Communities that oppose nuclear power plants within their borders are often allowed to lobby regulators and policy-makers, or seek recourse before the EU courts.

2016: The Belgian, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Netherlands communities You have sent a petition to the European Parliament expressing concern about the safety of the Tihange 2 nuclear plant near Liege after cracks were found in the reactors.

The petitioners were concerned about “the fact that only the relevant country decides about shutting down a nuclear power station.” But the EU disagreed that a shutdown was justified.

A subsequent case in the European Court of Justice brought by activists also failed to shutter Belgian plants that include the Doel reactor near Antwerp.

Cross-border calls for the closure of the nuclear power plant at Tihange, Belgium due to safety concerns sparked by cross-border concerns

Should France unilaterally increase its nuclear fleet that is getting old?

The petition against the Belgian plants drew a definitive responseThe European Commission’s position on the question of national or transboundary jurisdiction

“The decision to operate a nuclear power plant remains with the Member State, which is also responsible for ensuring its safe operation,” the Commission wrote in 2018.

That decision is playing out with France’s unilateral decision to extend the life of its ageing nuclear infrastructure, and President Emanuel Macron’s recent announcement that France will invest in “groundbreaking” small modular reactors as part of its commitment to reduce CO2 emissions.

France’s nuclear power generation declined to its lowest level in 2025 since 1995. According to the, the nuclear share in France’s electricity mix in 2020 was also the lowest since 1985. 2021 World Nuclear Industry Status Report. The same report showed that renewables are rapidly outpacing nuclear energy, causing the latter’s share of global gross electricity fall from over 17% to around 10% in the last 25 years.

By contrast, the OECD’s Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Energy Agency have reportedThe extension or “long-term operation” of older nuclear fleets is a cost-effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The NEA stated that “continuing operation of existing nuclear power stations is one of the most cost-effective investments opportunities for low-carbon generation, in many regions,” in a statement to DW.

But while German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has said he respects the right of France to make nuclear a key part of its climate ambition, his foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock, said Germany would oppose France’s push to have nuclear sanctioned as a “green investment” by the European Commission. The German government remains divided on the EU’s draft energy proposal released on New Year’s Eve.

Poland approved six reactors at two locations along Germany’s eastern border in early 2021. These locations are located on the Baltic Sea, which is only 150 km (93 miles) away from Germany.

“There is a 20% probability that Germany would be affected by an accident at the planned nuclear power plant,” the chairwoman of the Bundestag Committee on the Environment, Sylvia Kotting-Uhl, told DW in May. A “worst-case scenario” would see 1.8 million Germans exposed to radiation, including in the capital, Berlin.

Poland has insisted that the plants will be safe. Despite German protests, few seem willing or able to interfere in the “energy sovereignty” of national states.

Stefan Kirchner pointed out that the lack of veto power in neighboring states will mean that historic cooperation based upon existing treaties and conventions is the best way forward.

Edited By: Tamsin W. Walker