DULUTH Grant Merritt was an environmental lawyer who fought against the iron mining industry that his ancestors helped to create. He died Wednesday at his home in New Hope (Minnesota). He was 88.

Although the cause of death has not been determined, the family believes that it could have been heart-related.

Merritt was born Feb. 27, 1934 to Alice Merritt and Glen J. Merritt. Merritt is Duluths postmaster. Merritt grew in Duluths Hunters Park neighbourhood and graduated from Central High School, and the University of Minnesota Duluth.

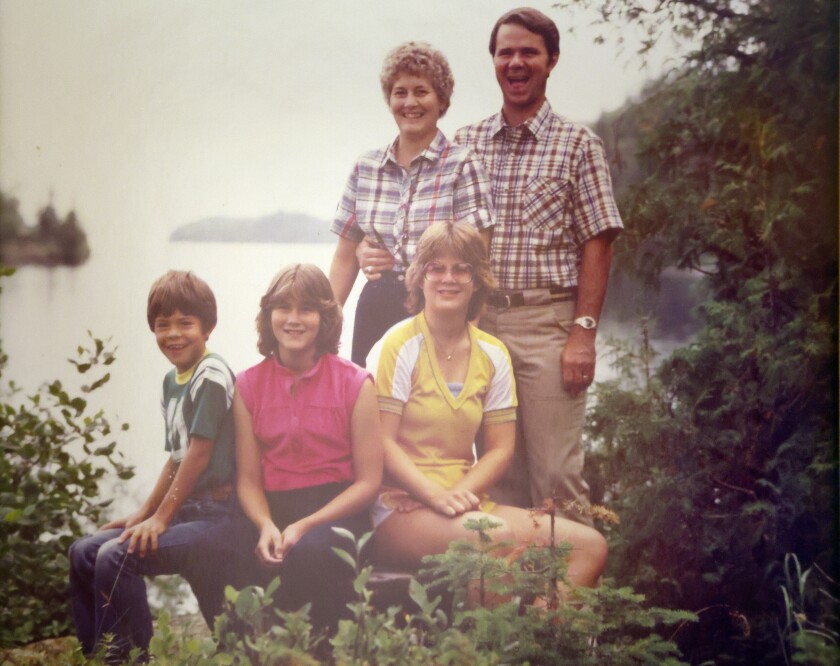

Contributed / Grant Merritt

After his military service, Merritt obtained a law degree. He then fought Reserve Mining in Silver Bay and got them to stop dumping taconite wastes into Lake Superior. Merritt was first a private attorney working with grassroots groups, and then he became the first commissioner for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, 1971-1975.

Merritt, who spoke to the News Tribune last summer, said that although it was ironic that he comes from a mining background, he fought for the Armco Republic Reserve Mining Company.

Merritts grandfather, Alfred Merritt and great uncles were the “Seven Iron Men”, who discovered iron ore in the Mesabi Range and established the Mountain Iron Mine in 1890.

Merritt stated, “But we didn’t try to put (Reserve Mining] out of business. We said you should just go land with those tailings, like every other company around the world.”

Those efforts were successful. In 1980, Reserve stopped dumping 67,000 tonnes of taconite tailings daily into Lake Superior. Instead, it pumped them into Milepost 7 tailings basin that it constructed a few kilometres inland.

The basin is still in use 42 years later and Merritt, up to his death, remained an environmental watchdog. Merritt was still emailing and calling government officials and the press to express his concerns about Milepost 7. Cleveland-Cliffs owns the former Reserve Mining operation. It is now called Northshore Mining.

Andrew Slade, Minnesota Environmental Partnership’s Great Lakes program director, said that Merritts had that institutional knowledge. He said Merritt’s sense of duty to the environment kept Merritt fighting the same issues for decades. He wanted to see them through.

Merritt and Slade also worked together on other environmental issues in the Northland such as the U.S Army Corps of Engineers placing dredged harbor material at Park Point that contained metal waste. Merritt was also involved in a related harbor-dredge issue back at Milepost 7 in the 1970s.

He loved Lake Superior. He would not give up on trying to keep Superior pristine, Carolyn Klein (Merritts’ daughter) said.

Merritt wrote in his 2018 autobiography Iron and Water about looking out of the window of Historic Old Central High School, Park Point, and thinking about the lake rather than physics class.

Merritt wrote that my family history and a public school education that encouraged student participation were the foundations of my commitment to citizen advocacy in my adult years.

He was a passionate sharer of his family history with his children, grandchildren, and anyone else who would be interested.

Contributed / Grant Merritt

Klein said that his love of Lake Superior, the outdoors, and his family’s trips to their property on Lost Lake near Hovland was passed to them through camping trips, visits and stays at the cabin at Isle Royale National Park. This unique arrangement is still in effect.

Merritt’s grandfather Alfred Merritt had visited Isle Royale in 1866 as a deckhand on an schooner. He returned to seek copper and eventually purchased 14 islands around Isle Royale, where he built a cottage. The cottage was destroyed and the Merritts moved to a cabin further into Tobin Harbor.

Merritt Island is home to the Merritt name. Merritt Lane is the narrow strip of water that separates Merritt Island from its neighboring islands. Merritt Lane Campground is home to Merritt Lane.

Klein recollects the time her father used to boat around Blake Point Isle Royales northeast tip, turning into Merritt Lane.

Klein said that he would turn the motor off and tell us to just sit down and enjoy the quiet. He felt so calm outside, Klein said.

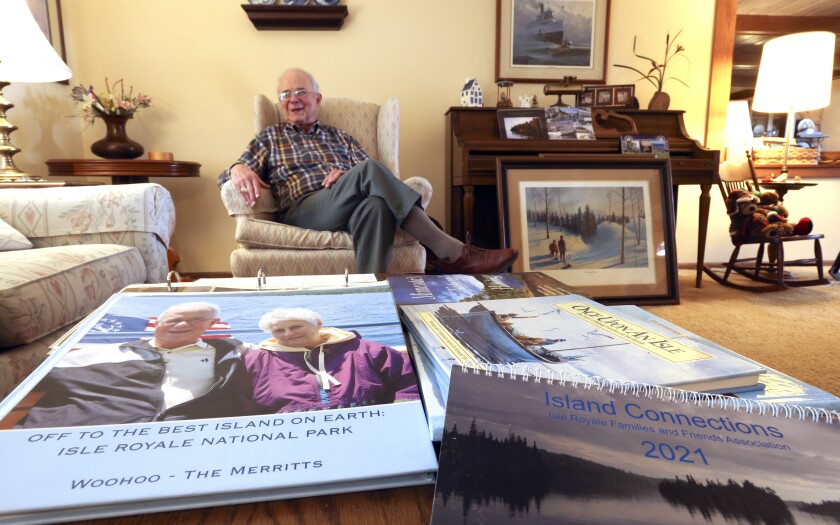

Merritt kept his family’s presence on the island alive by visiting the cabin every year for a few weeks. He estimated that he had only missed four years since his first trip in 1939, when he was just five years old.

Steve Kuchera / File / Duluth News Tribune

Families with cabins on Isle Royale were forced to sell or enter into a lifetime lease when it became a National Park. This gave the former cabin owners and their children exclusive rights to use the cabins during the summer for the rest of their lives.

Children who were minors at the time the park was established, such as Merritt, were often excluded from the lifetime leases. He lobbied for a solution for over 20 years and finally in 1977, a special-use permit was approved that would allow children who were minors to have lifetime access to their cabin.

People like Lou Mattson, Merritt’s neighbor in Tobin Harbor, and his family could move in. Merritt and Mattson had a Tobin Harbor fishery, and Mattson grew with Merritt. They also got into hijinks on the island as boys.

Merritt was the one he credited for lobbying for the special use permits, so he and others could have unlimited access to their cabins. He called it a very favorable deal for the families.

Mattson said Grant was certainly an advocate of the people who were at park.

Merritt would later form the Isle Royale Original Families Association (Isle Royale Families and Friends Association) in 1982.

John Snell, whose family cabin can be heard from the Merritt cabin said that he saw a need for a community to come together and acknowledge the scarce resource we were all becoming. He was the one who stated that this is an important tradition on the island, the sense of connection that fishermen and other families had before the island became a national park.

Steve Kuchera / File / Duluth News Tribune

Merritt and his family would shout Wahoo! a lot, which Snell would often hear. He would shout Wahoo at boats passing their cabin, which he translated as Hello, So Good to See You or How Are You? in the Merritt Language.

Merritt hoped that the families who predated the creation the national park would continue to be present on the island.

Snell said that Merritt’s Isle Royale meant everything.

He said that it was where his soul was.

Merritt is survived and cherished by Marilyn, his daughters Linda Tully and Carolyn Klein, as well as Mary Alice Scheibe, nine grandchildren, and two great grandchildren.

Stephen Tully, his grandson, and Kaydence Tully are his heirs.

Merritt’s family plans to hold a service in the Twin Cities next month. The date has not yet been set.

The Rev. Skip Reeves will officiate. Merritt & Reeves wrote a quote to be read at his funeral: Grant had a heart the size of Lake Superior and a spirit to match. He had an uncompromising passion for protecting the environment.

Steve Kuchera / File / Duluth News Tribune