[ad_1]

The remaining “carbon budget” specifies the maximum amount of CO2 that may be emitted to stabilise warming at a particular level – such as the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C target.

Carbon budgets have played an important role in national and international climate policy – not least being a key rationale for adopting net-zero emissions targets.

Yet, there are many sources of uncertainty that make it challenging to estimate the remaining carbon budget in real-world conditions – especially for the most ambitious mitigation targets.

In our new study, published in Nature’s Communications Earth and EnvironmentJournal, we present an integrated method to quantify these uncertainties and incorporate them into estimates for the remaining carbon budget.

We estimate that there will be a range of 230 to 440bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) by 2020, which is a two-in-3 to one-in-2 chance of the 1.5C target being met. pre-industrial times.

This is equivalent to six to 11 years of global emission if current rates are maintained and they do not decline.

However, we emphasise that the remaining carbon budget is not a single number, but rather a distribution that reflects the probability of meeting a target – that is, the greater the chance of meeting the budget, the smaller amount of CO2 that can be emitted.

It is possible that 1.5C’s remaining carbon budget has been exceeded by approximately one in six.

The budget would be more durable if emissions fall. Our 230-440bn-tonne range would fit with net-zero targets. This would mean that CO2 emissions would decrease linearly between 2019 levels and net-zero by 2032-2042.

The 7% drop in emissions caused by Covid lockdowns in 2020This is in line with the rate of decline. This highlights how important it is to be proactive. economic recovery effortsThese measures are intended to reduce emissions further, so that the 1.5C target is still within reach.

Geophysical basis of carbon remaining in the carbon budget

The remaining carbon budget is derived from the approximately linear relationshipBetween cumulative CO2 emissions, and the warming of Earth that they cause. In other words, a tonne CO2 emitted today, yesterday, or 50 years ago will all lead to roughly the same amount warming.

Carbon budgets are not just expressed as the remaining CO2 but also include carbon budgets. warming contributions from non-CO2 forcing(This article will discuss.)

The relationship between cumulative CO2 emissions and temperature change is known as the “Transient Climate Response to Cumulative Emissions” (TCRE) and is a robust predictor of CO2-induced warming across a wide range of emissions levels and pathways.

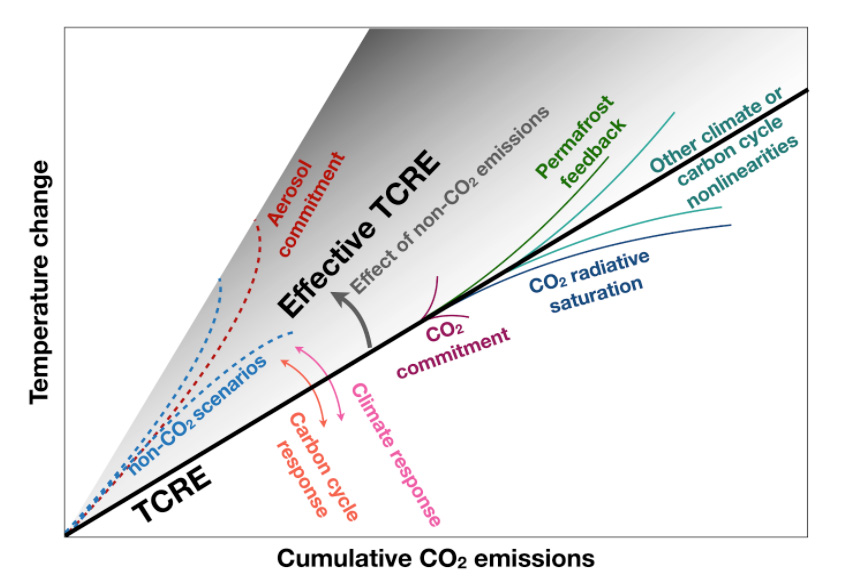

In the chart below – from our recent Nature Geoscience perspective – TCRE is shown by the straight black line, highlighting the direct relationship between CO2 emissions and warming.

We don’t live in a CO2-only world. There are lots of different factors that affect this relationship – shown by the coloured arrows in the chart – such as non-CO2 emissions and the response of the carbon cycle to rising CO2.

These factors make it difficult to estimate the TCRE based on observed quantities in a real world setting.

We first estimated the TCRE using three quantities that describe the current climate system. This was taking into account uncertainties.

1. The observed human-caused warming;

2. Total historical CO2 emissions

3. The percentage of temperature rise observed that is due to CO2 compared with non-CO2 emissions.

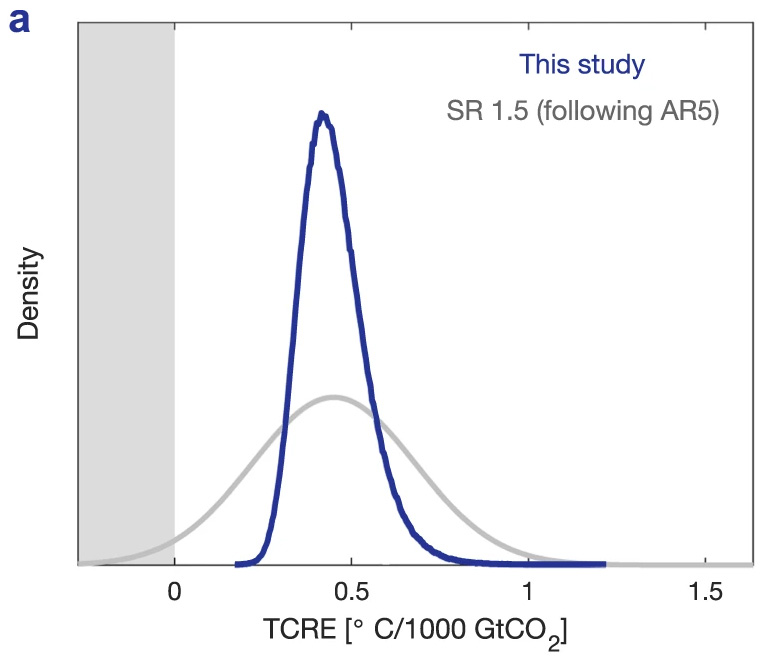

Our best estimate of TCRE is 0.44C for 1,000GtCO2 emitted. This is similar to the one used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) special report on 1.5C(SR15), published in 2018.

However, the range across all possible values of our TCRE estimate – known as the “uncertainty distribution” – is considerably narrower than that assessed by the IPCC in the SR15 report and the fifth assessment report (AR5), published in 2013-14. This is evident in the chart below which shows our TCRE estimate (blue) and AR5/SR15’s (grey). We are able to narrow the TCRE by making use of updated observational constraints, which are able to more clearly rule out both higher and lower TCRE values.

Assessment of the remaining carbon budget

To estimate the carbon budget’s distribution, we used our estimate of TCRE and added uncertainty to two other key parameters.

4. The unrealised warminga result of emissions already present in the atmosphere

5. The uncertainty associated with the climate system’s response to non-CO2 emissions, such as methaneAnd nitrous oxide;

These five parameters, together with the three previously mentioned quantities, encompass all major sources geophysical uncertainty that affect the remaining carbon budget.

The chart below shows that our best estimate of 1.5C’s remaining carbon budget is 440GtCO2 starting in 2020. With a range of between 230-670GtCO2, this reflects a 67-33% chance of not exceeding its temperature target. The grey rectangle shows that we believe there is a 17% chance that 1.5C’s remaining carbon budget has been exceeded.

These values are smaller than those reported by the IPCC 1.5C reportBecause our distribution includes the uncertainty from non-CO2 forcing and historical warming, which were separately assessed by SR15 and not included in the main SR15 budget estimates,

We have created a carbon budget estimate which includes all relevant uncertainties and is constrained with observations. This estimate is therefore more reliable for 1.5C.

Accounting for socioeconomic scenario uncertainty

Although scientific uncertainty is a reflection of incomplete understanding of the physical and biological processes that make up the climate system, it’s important to consider the possible choices society could make that will affect future CO2 emissions.

For example, a key “socioeconomic” uncertainty that affects the size of the remaining carbon budget is the future pathway of non-CO2 emissions.

In our framework, socioeconomic uncertainties are treated separately. Because socioeconomic uncertainties are dependent on human mitigation decisions, they are not as well-suited for formal distributions.

Instead, we use emission scenarios taken from the SR15 scenario databaseTo estimate the range of possible combinations of CO2 and non-CO2 forcing that could be used to reach net-zero CO2 emissions. This approach allows us explore non-CO2 emission trajectories to net-zero carbon dioxide scenarios that are compatible with the Paris Agreement goal.

The chart below shows that this scenario variation can shift the distribution of the 1.5C carbon budget (blueline) by 170GtCO2 either way. This means that future non-CO2 emission levels could decrease the budget by 170GtCO2, while future emissions could be low (purple line). Future emissions could also increase the budget by the same amount (green line).

Path to net-zero

The small amount of carbon remaining in the budget highlights the importance of achieving net-zero CO2 emissions goals at the international. nationalMoreover, it can be used at subnational levels.

This is, perhaps, the most pressing policy implication of carbon budgets – that to stabilise global temperatures at any level, the international community needs to eliminate net CO2 emissions.

The figure below, for example, illustrates how quickly global CO2 emissions need to fall in order to stay within the 1.5C (blue line) and “well below” 2C (yellow) budgets. Global CO2 emissions will reach net-zero in 2040 and 2060 if the carbon budgets for 1.5C and well below 2C remain.

The dark red line represents the trend in global emissions prior to the coronavirus crises. However, emissions between 2019 (“orange star”) and 2020 (“purple star”) actually exceeded the estimates. dropped by 7%. This is consistent with 1.5C’s annual emission decrease.

The way forward

Scientists need to work to reduce uncertainty surrounding the remaining budgets for the most ambitious global climate targets in order to better inform this policy goal. This includes both better understanding uncertain processes and reporting on our choices and assumptions so that we can calculate remaining carbon budgets consistently, clearly, and transparently.

Another policy question is whether the global remaining carbon budget could – or should – be allocated to individual nations or other entities like corporations or municipalities.

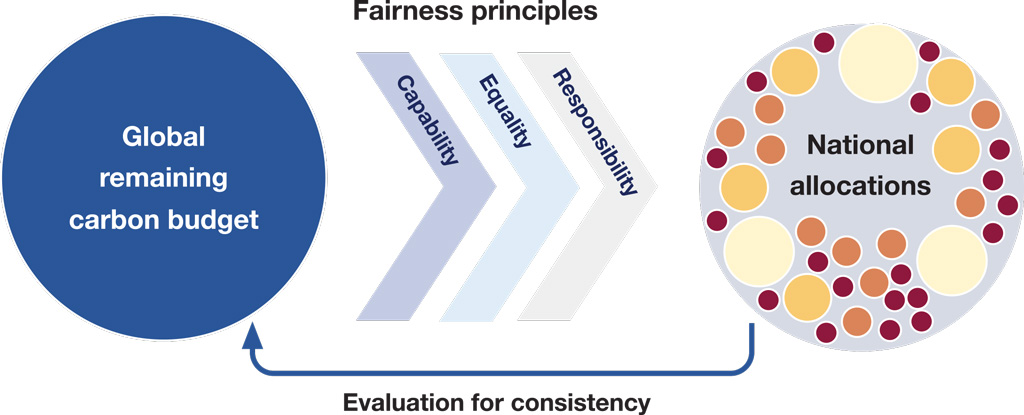

“Fairness principles” – illustrated in the figure below – present a substantial challenge in allocating the (already small) remaining carbon budget among different countries in an equitable way.

For example, any national allocation of the global budget requires consideration of each country’s ability to decrease emissions and their responsibility for the past emissions – as well as the level of equity needed to justify a given allocation.

International cooperation and oversight is required to ensure that all national emission targets do not exceed the remaining carbon balance. This will enable countries to strengthen their national commitments, and align future target setting with the best science.

Scientists need to collaborate with policymakers and social scientists in order to communicate the consequences of remaining carbon budgets in ways that can improve and strengthen national climate policy.

From a societal perspective, it is important that the remaining carbon budget be seen as a global limit for emissions. This is something that all of us need to work towards.

All countries have a part to play in this common goal. Only if we all work together in the near-term will we be able to achieve the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals.

Matthews, H. D. Tokarska, K. B. et al. (2021) An integrated approach to quantifying uncertainties in the remaining carbon budget, Communications Earth & Environment, doi:10.1038/s43247-020-00064-9

Matthews, H. D. et al. (2020) Opportunities and challenges of using remaining carbon budgets as a guide to climate policy, Nature Geoscience doi:10.1038/s41561-020-00663-3

Update: This article was revised on 22/01/2021 in order to correct “one-in-3” chance to “two–in-three” chance in the fifth paragraph.

Sharelines from this story

[ad_2]

Source link