[ad_1]

Global warming was the precursor to climate change. Before that, it was holes caused by greenhouse gasses.

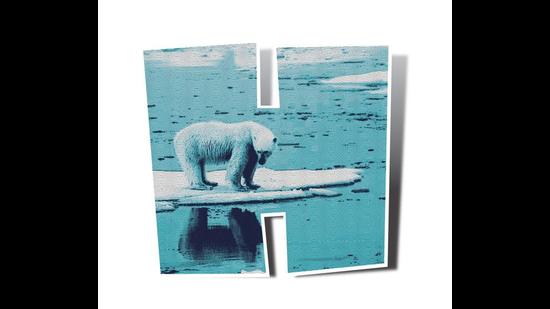

Now, it’s the climate crisis, caused by a combination of rising temperatures, rising sea levels, a slowing Gulf Stream, intensifying weather events, and increasingly erratic rainfall. Hence, crisis.

It makes sense to extrapolate from this. If this is what 1.1°C (warmer than preindustrial levels) looks, 1.5°C will be potentially frightening. And 2 degrees is unlivable.

As the once debated is-it-or-isn’t-it phenomenon of global warming has turned into undeniable changes we see today — from superstorms and cyclones to sweeping wildfires, record-setting summer and winter extremes, torrential rain in months that saw no rain, and snow and hail in parts that see no snow; as the climate has become more extreme and unpredictable; and as our species attempts to navigate this change, a new language has developed to talk about the phenomenon.

So we have, for example, ideas of climate justice or environmental racism. This was the topic around which world leaders gave passionate speeches at CoP26 in Nov. Tulavu’s foreign affairs minister Simon Kofe stood knee-deep in the ocean, in his home country, and said to the world: “We are sinking.” Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley described a goal of 2 degrees as a “death sentence” for her nation and many other island nations that would go under.

The terms “climate justice” and “environmental racism” are pegged to the idea that attempts to mitigate rising temperatures and the impacts of the climate crisis must focus on smaller economies that stand to be worst-affected, rather than almost exclusively on keeping the world’s biggest cities and most powerful countries stable. You can read more about that in the Wknd-A-Z.

Similarly, the term “triple bottom line” is both a hope and a warning. It is the idea of companies aiming for three things simultaneously, profits, the good and the elimination of pollution. This idea is reflected in the fact that some soft drink companies have plastic and water recycling programs, while cigarette manufacturers plant forests. How many trees have been planted, and how much water has been recycled? Take a look at the numbers. Far too often, triple bottom-line claims are made by greenwashing, a practice that transforms polluting activities into hollow PR stunts.

The language used to describe climate change and conservation is a product that has evolved with the times. Many new terms are simple and easy to remember. Many terms are self-explanatory, including keystone species, circular economy, and net-zero emission. It’s a language designed to encourage inclusivity, action and hope.

Some terms have become movements. Net-zero is the new standard. It is the point at which we can remove from the atmosphere as much greenhouse gases as we put in. This can be achieved using natural and man-made carbon sources and can keep the temperature below 1.5 degrees Celsius (above the pre-industrial levels of 1850).

ECO-SPEAK

Some terms matter, not because they’re new or catchy but because they’re often misunderstood, with disastrous effects. The terms “grassland” and “wasteland”, for instance, are used interchangeably by planners, with devastating consequences for the numerous species that live nowhere else on Earth, and for the delicate ecosystems they help support (as well as for basic land-use; lost grasslands mean worse flooding, poor soil retention).

Pest is also a term that is often misused to describe majestic animals like the nilgai or to cause ecosystems to be destroyed by overuse of chemical pesticides.

Although renewable energy and lithium ion batteries are often referred to as the “magic wand”, they may not be as powerful as they claim. Continue reading to learn more.

And read on also for why imperfections might be better than the alternative, why space shouldn’t be the billionaires’ newest playground, what it is that makes palm oils so awful, and just how much of you might just be microplastics.

.

Agricultural land:The average Indian farm size has fallen to 1 hectare from its 1970s peak of 145 million. Conservationists are concerned about the possibility that farmland in India is being used for farming as it becomes less cohesive and the climate becomes more unpredictable. Meanwhile, agricultural land near India’s mushrooming cities is at risk too. What is a farm and how can we grow it more sustainably? What’s the best thing to be eating, from an ecological standpoint? These will be key questions in our efforts to solve the climate crisis.

Big coal: India is the world’s second-largest consumer of coal, according to data from Statista. More than half of the country’s electricity is still produced by burning this polluting fossil fuel. Meanwhile, India’s population is set to hit 1.5 billion by 2030, according to the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. According to estimates by International Energy Agency, India must increase its generating capacity in order to meet the demand for all of Europe over the next 20 year. Will this, too, be generated from coal? Renewable sources are in play, but don’t have a starring role yet.

Circular economy A circular economy is a system that allows products and materials to be shared. The benefits are clear: it’s good for the environment, fewer virgin materials are extracted, there is less waste of production processes and raw materials such as water, and less waste makes it to landfills. The trick is to make the circular economy profitable and scalable. Small businesses are making profits by upcycling stale bread and beer into beer and polluted waters into potable. Companies that specialize in helping others close the loop also are popping up. See Wknd’s Urban page for more.

Downgrade: Although India’s average solid waste generation is only a fraction of the global average for the country, India has the largest total solid waste generation. The more we consume, we pollute. You can downgrade by using less stuff and thinking before you click on everything, from snacks to knickknacks. Capitalist societies face new challenges when they have to deal with a downgraded lifestyle. We are all at this point. These economies are dependent upon endless cycles and consumption. Finding a way to slow that cycle could be the vital climate action no one’s talking about.

Environmental racism: Globally and locally, the climate crisis has disproportionately affected the poor, while the wealthy have the ability to protect their lifestyles and consumption habits. This disparity is now being called environmental racism. Which doesn’t put us in the clear. Within India, over 40% of all those displaced are from tribal groups, though tribals comprise only about eight of the country’s population, according to a report released in 2012 by the UN Working Group on Human Rights in India. Worse, many of the projects that enable such disadvantaged to be displaced serve wealthy urban and /or rural populations and lifestyles, perpetuating the cycle of inequality.

Forests:India categorizes orchards as monocultures, plantations, and plantations. The Forest Survey of India defines forest cover thus: “All lands, more than 1 ha in area with a tree canopy density of 10% irrespective of ownership and legal status.” Some forest areas, meanwhile, contain roads, mines and agricultural land instead. The forest tag is used to deny forest dwellers and tribes their right to forage, gather firewood and otherwise live off the land (in what remains, let’s be honest, some of the most environmentally sustainable lifestyles in the entire world). In 2021, the union government announced that it is revisiting the definition of forest altogether, in attempt to “streamline” legislation. What this would mean for India’s remaining green lungs is not yet clear.

Grasslands: They’re flat, expansive and appear lifeless. This is why grasslands in India are often referred to as “wastelands” and left unprotected. They are vital ecosystems that support a variety of species. India’s grasslands are home to elusive and threatened species, from the great Indian bustard to Indian grey wolf, as well as numerous endemic species of reptile, mammal, amphibian and bird. Because they are often incorrectly categorised, India’s grasslands are shrinking. The Nilgiri plateau, which is home to the unique shola grasslands of India, has less than 15% remaining intact. As elsewhere, the land has been destroyed by power projects, resorts and roads, farms, and homes.

Human-animal conflict: The incidence of human-animal conflict is on the rise as wildlife reserves are destroyed and their green lungs shrink. With roads, power plants, and entire towns being built, many areas have been divided from what was once a sanctuary. In India, new species are featuring in these clashes, from sloth bears driven into fields because the water bodies in their forests have shrunk, to elephants running amok in new parts after ancient corridors were disturbed, and snakes and leopards forced out of their homes and into human settlements that didn’t exist a few years earlier. In all cases, the question is the exact same: How much room can they take?

Imperfect: There’s a case for doing a little for the environment, doing what one can, even if it can’t be done perfectly. Can’t always eat local? Be flexible and eat animal-based foods in moderation. Can’t ditch all plastic? Reduce your single-use plastic use to a minimum. Transition slowly, set realistic goals; that way, they’re likely to last longer. The imperfect movement is also referred to when you pick produce with blotches and blemishes. Is that a knobbly orange carrot? Grab it. It’s probably been tampered with far less than the ones with no curves.

Climate justice: “We are sinking,” Tulavu’s foreign affairs minister Simon Kofe said, in his CoP26 speech in November. His podium was knee-deep in water in his homeland. The global climate goals are to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. A worst-case scenario is 2 degrees. Mia Mottley, Barbados prime minister, said that two degrees Celsius is a death sentence to many vulnerable islands nations that would be submerged. Climate justice advocates for rich nations with a greater historical burden to spend more and do more to combat the crisis. This is especially true for smaller economies that are more vulnerable to the climate change impact.

Keystone speciesA keystone is a slab that is wedged into an arch’s summit to prevent it from collapsing. An ecosystem’s keystone species is the one that prevents it from collapsing. The most important keystone species are elephants, tigers, and whales. However, in delicate ecosystems around world, a keystone specie may also be a species of bee, a small amphibian, a fungus or a grass, a tree, or a flowering plants. Even if one only cares about the big picture, it’s not enough to protect the charismatic, large-eyed, and charismatic. The small and the hidden can also be important.

Lithium-ion battery: Electric vehicles will change the world in new ways that are not yet apparent. Let’s take lithium. It’s a core component in an EV’s rechargeable battery, and as millions of EVs hit the roads over the next few years — India alone is aiming for EVs to account for 30% of all new cars sold by 2030 — expect to hear a lot more about Bolivia, home to 25% of the world’s lithium deposits. The extraction process is expensive and dangerous, and the mines are also very dangerous. And it’s still not clear how this toxic element can safely be returned to the earth.

Microplastics: Microplastics, a subset of single-use plastics, are the real threat. Tiny fibres and fragments have drifted out of products (they’re in everything from tea bags to tennis balls, detergents, cigarette butts and glitter) and found their way into oceans, rivers, marine life, Arctic ice. They’re in the air, in drinking water, and in more or less every person on the planet too. Microplastics are being linked to higher cancer risk and birth defects in children.

Net-zero:The idea of net zero emissions is a hypothetical ideal in which the amount of greenhouse gases produced would equal the amount that is removed from the atmosphere by natural and artificial carbon sinks. There is great hope that humans can limit the damage done by human activity if the world can achieve net zero global warming and maintain a temperature of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Net-zero emissions is possible on a planet already 1.1 degrees Celsius hotter than it was in 1850. This is despite all the climate chaos and destruction that this has caused. Twenty years from now, if the world isn’t close to net-zero emissions, the result will be a climate crisis that intensifies exponentially.

Oil palm plantations:Palm oil can be found in everything from shampoo to icecream. If an agrarian community wants to get rich quick, it’s a simple question of planting the palms and waiting for the money to flow in. It’s such an effective path to riches that, in Indonesia, oil palm plantations have replaced thousands of acres of tropical rainforest. Viral images show endangered orangutans holding on to the forest that was left behind, despite the fact that many acres have been destroyed. India pledged last year to triple palm oil production using land in the ecologically fragile north-eastern states as well as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Pest: Because of India’s tough wildlife laws (implementation is another matter), an animal whose existence is inconvenient to human interests sometimes crosses the line from wild to pestilent. So the term “pest” in India includes certain kinds of bollworm and caterpillar, but also the majestic nilgai and the wild boar. You can tag them pests to make it easier for them to be killed, and often prevent crops from getting trampled. Even traditional pests are being mishandled. Pesticide misuse is another example of a good invention that has led to the destruction of entire bird-insect ecosystems.

Quantification of climate change impacts: How do you measure the effects of climate changes or the desired outcomes? Scientists have begun to break it into numbers in an effort to make goals and threats more understandable. 1.5 degrees Celsius (above preindustrial levels) is the minimum temperature at which we must stop warming. 350 ppm is the upper limit for CO2 content in the air; the global average is currently 412.5 ppm, according to a 2020 report by the US’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The Trillion Tree Campaign aims to increase the planet’s green cover by that much. And they’re all ways to explain climate change in numbers.

Renewable energy: India has pledged to generate half of its energy from non-fossilfuels by 2030 and five times more energy from renewable sources by 2030 (currently at 100 gigawatts). There has been massive investment in renewable power technologies by some of the country’s biggest players, but critics are still sceptical about the 2030 target. A point to note here is that “renewable” refers to the source of the energy generated. All over the globe, there is a need to improve the sustainability, efficiency, and recyclability.

Sustainable materials: Production has been synonymous with pollution since the industrial revolution. There is a global movement to return the local, biodegradable and non-energy-intensive processes and materials that were the norm before global supply chains and machines. This movement has led to vegan alternatives to silk, leather, restaurants that source locally or forage, concrete-free structures with built in renewable power and water recycling plants, and many other innovations. This is the challenge: scaling up at an affordable rate.

Triple bottom line This idea states that companies should aim for three things simultaneously in the face of climate crisis: profit, community good, and pollution reduction. This can often mean investing in pollution mitigation and changing processes. There are also soft drink companies that recycle plastic and water; cigarette manufacturers planting forests. How many trees are actually being planted and how much water is recycled? You can see that triple-bottom-line companies are often really good at greenwashing, which is the practice of making polluting activities sound hollow PR exercises for their benefit.

Urban habitats: The intangibles that keep animals away — noise, lights, traffic fumes — only became apparent in the early months of the pandemic, when nilgai tiptoed down the streets of Noida, spotted deer were seen in Tirupati, and a rhino wandered into Guwahati. Nature has learned to live alongside concrete blocks and tarred streets. Even the cement jungle in Mumbai is still home to flamingoes as well as leopards and dolphins. These delicately reframed balances are falling apart as our cities expand into neighboring forests and green lungs, and Mumbai expands outwards into the ocean via it coastal road.

Viable population: This is the minimum number required to ensure that a species can survive and thrive in the wild. This number varies for different species. Certain animals and birds, such as the great Indian bustard or white-bellied heron are currently at an important inflection point. According to data from Bombay Natural History Society there are approximately 125 great Indian bustards living in the wild. There are also a few in neighboring states. The smaller populations are likely to die out, but the Rajasthan population, if allowed the growth now, could achieve some stability. Like lions and tigers, the population of Rajasthan could grow to the point that small groups could be moved to areas where they have died.

Waste stream: The item’s waste stream is the journey it takes after it has lost its function. Every object has one. Although there is profit in managing waste well and new products are being developed all the time, it can take many years to refine their waste streams. Although electric vehicles are a viable option to replace fossil fuels, they contain toxic cobalt and lithium. How would these batteries be disposed? What happens to the photovoltaic panels in solar panels after they have died? As more of these questions are raised each year, they will be answered.

Space X and the new age space race: At this point, they’re essentially exorbitant, repetitive, polluting joyrides. Billionaires are trying to outdo one another by bobbing around in low orbit, creating new revenue streams with plans for regular tourist shuttles and space hotels, among other things. This is yet another example shortsightedness, self-indulgence, and ecologically harmful excess. That they are burning up precious resources and exorbitant sums, at a critical period in the planet’s future. Only a few people will be able to see Earth from space. Even then, they will need to return to the planet and address its climate crisis.

Yamuna, India’s waterbodies, and marine ecosystems: The Yamuna looked amazing, as he frothed around devotees during Chhath Puja. Sadly, it’s not alone. Mumbai’s Mithi River, Bengaluru’s lakes, Kolkata’s Hooghly are all grappling with extreme pollution from untreated sewage and industrial effluents. The oceans are where pollution is more widespread, but less visible and less studied. Everything from microplastics and plastic waste to sound pollution and ghostnets are affecting fragile ecosystems. In Bengaluru, a citizens’ group has revived five lakes over ten years; in Mumbai, people have fought to save 80 hectares of flamingo-roosting wetlands. The idea was to make the patch a golf course.

Zoonotic diseasesThis is the term for diseases transmitted from animals to people. It’s a term made familiar by 2020, and the bats that are suspected to have passed the novel coronavirus, Sars-CoV-2, onto the human population. The epidemiologists expect that there will be more new diseases as more species that were not previously in contact with humans. This is due to changing migration routes, shifting habitats and habitat destruction. This is a bad thing, as we have seen it happen with Ebola, Zika, and Covid-19.

With HT Premium, you have unlimited digital access

Subscribe Now to continue reading