[ad_1]

It can be difficult to engage people in discussions about climate change. Climate conversations can be technical and dry, making them difficult to understand how they relate to our lives. As a matter of fact, Historical researcher I’ve been figuring out how we can make this connection clearer, and believe that taking a look at our family histories might hold the answer.

Although climate change may seem distant and abstract, our own history is intrinsically personal. The ability to trace a family tree allows you to see how historical events, as well as those that influenced them, have been reflected in your family tree. Climate ChangeChanges in life paths can alter your life. Through pilot research with my own family tree, I’ve found that family history can be a useful tool for understanding how the root processes that kickstarted climate change created the world we now inhabit.

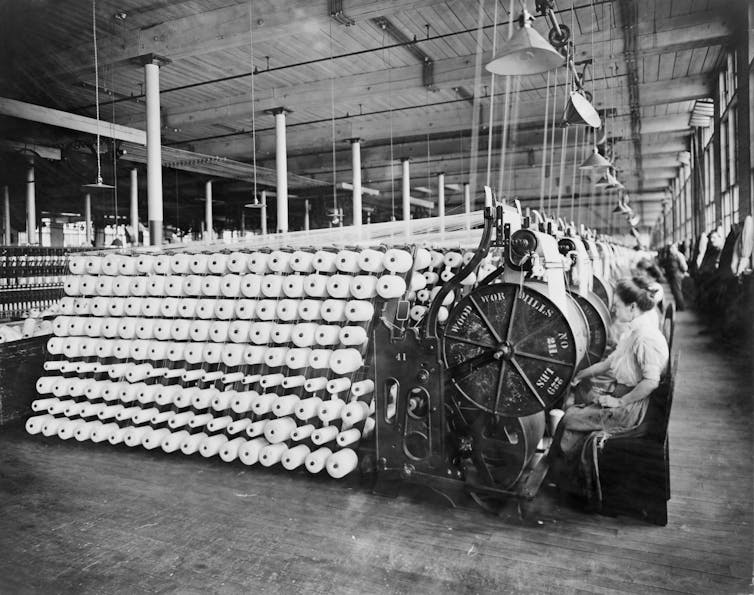

Simply put, climate change is the outcome of two processes. industrialisation Colonialism. Industrialisation is when a society’s primary mode of production shifts from manual agricultural labour to machine-aided manufacturing. Colonialism is when one country occupies and controls another. This usually involves violence and exploitation.

Both are supported by a Culture of extraction: The belief that all resources (natural, such as trees, and cultural like traditions) can be tapped into in some way.

Shutterstock

This is reflected in British history’s intertwined growth of both the industrial revolution (Iron Revolution) and the British empire. Both were fed by coal mining to fuel factories, railways, and steamships; extracting raw materials needed to make goods; and exploiting labour from subjugated countries and the British working class.

Family branches

Let’s look at some examples from my own family. Samuel Polyblank (born around 1816), one of my great-great-great-grandfathers, was a shipwright from London’s East End. His ships helped to meet international trade demand, transporting goods to and fro the colonies. They may have even been used by the East India Company, the world’s first global corporate superpower, and a key player in colonial rule and exploitation in Asia.

Samuel Polyblank was a member of a system through his work. Which impacts – including widespread deforestation, pollution, soil sterilisation and The collapse of biodiversity – continue to be felt today.

Another example is Daniel Winchester (born circa 1791). One of my great-great-great-great-grandfathers, he was an iron founderFrom Bristol. Bristol is well-known for its many connections with the Slavery and to the British empire’s Plantations in the Caribbean. And what those plantations relied upon very heavily were imported supplies for fossil fuel-driven processing plants and factories – which were frequently made of iron.

Mira66/Flickr, CC BY -NC – SA

I don’t know for certain if Daniel Winchester’s work ended up in British plantations: but since at the time there were iron foundries in Bristol that made things which did, it’s not unlikely. And I know that Daniel made enough money to buy his own home and leave it to his son, a rare occurrence at a time when only a tiny proportion of Britain’s homes were occupied by their actual owners.

The Winchesters were not wealthy, but they still had to work manual jobs and depend on child labour to supplement what they earned. They were able to pass down their wealth to their children. Intergenerational wealth: A hallmark of privilege that was only available for a small percentage. It seems plausible that this was possible because they capitalized, knowingly and unknowingly, on the industrial demand that arose from slavery.

This is uncomfortable to acknowledge, but if we want to understand the roots of climate change, it’s exactly what we should consider. It’s improbable that either Daniel Winchester or Samuel Polyblank set out to promote slavery and colonial violence any more than they set out to promote climate change. Their world meant that it was possible for them to participate in the exploitative system of extractive production without having to confront it. It is similar to how we struggle to understand our individual influence in climate change today.

How to engage

One challenge is to engage personally with the Climate crisisYou may find out that your ancestors are complicit in actions that you would prefer to avoid. But this isn’t about blaming our ancestors, who may well have been exploited themselves.

Shutterstock

Understanding these connections can help us prioritize. Climate justiceWe can adopt eco-friendly behaviors in our daily lives, such as reducing meat consumption. Unsustainable travelWrite to your elected officialsYou can learn more about environmental issues in the community. So how might you think about your own family tree’s links to climate change? Here are my top questions:

-

Think about where your ancestors bought and used their products, and where they might have been involved in making them. How can these connect them with the industries and trade networks created by colonialism

-

What was the source of their wealth if they were rich? If they weren’t, what benefactors funded any hospitals or workhouses they may have used: and would those have existed without industry and colonialism?

-

What did they pass on? You should consider not only objects, but also wealth and property, as well skills and cultural practices. How can these legacy be made climate-friendly, such as by donating to environmental organizations?