[ad_1]

Daily life brings out many biological metaphors for cities. You may live close to an “arterial” road or in the “heart” of a metropolis. You may work in one of the city’s “nerve centres” or exercise in a park described as the city’s “lungs”.

This is a sign that there is underlying naturalism to our city-building thinking. Naturalism is the belief in one theory that unites natural and human systems.

This way of thinking has been a great way to deal with urban problems. Today, as the world’s cities face new problems, fresh urban visions are needed again.

Cities are facing a direct threat due to the impacts of climate change like extreme heat. What’s more, climate change is prompting peoplePeople move to cities from rural regions, which places pressure on urban infrastructure. So let’s look at how biological ideas are useful for building cities that can withstand these challenges.

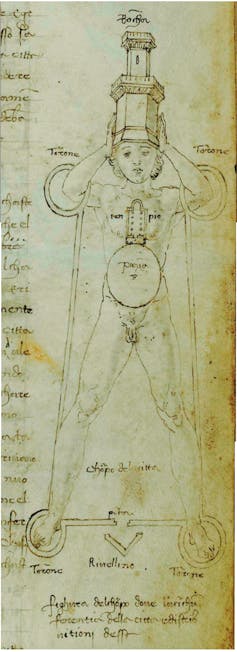

Turin Biblioteca Reale.

The city as a whole

Understanding of the 17th and 18th century was a major focus. Blood circulationand other bodily functions became crystallized. This knowledge could be used to create an Enlightenment vision where urban components mirror the functions of different body parts.

The image to the right shows Francesco di Giorgio Martini’s urban vision (1439-1501).

He believed cities should be planned with the centre of government located at the “head” – the most noble part of the body. From an elevated position – metaphorically and sometimes physically – governments could both be protected, and surveil the rest of the city-body.

According to di Giorgio Martini’s Thinking, a temple should be located at the city’s “heart” to guide its spirit. And piazza should be located at the “stomach”, guiding the city’s instinct and mixing the populace.

Numerous medieval and renaissance towns include a citadel on top of a hill. This type of city thinking is not common. culminated in the 20th century when the French-Swiss urban planner known as Le Corbusier conceived of a city with a decision-making “head”, separate from the residential and the industrial “bowels”.

This led to the creation of new capitals like Brasilia (Brazil) and Chandigarh, a state capital in northern India.

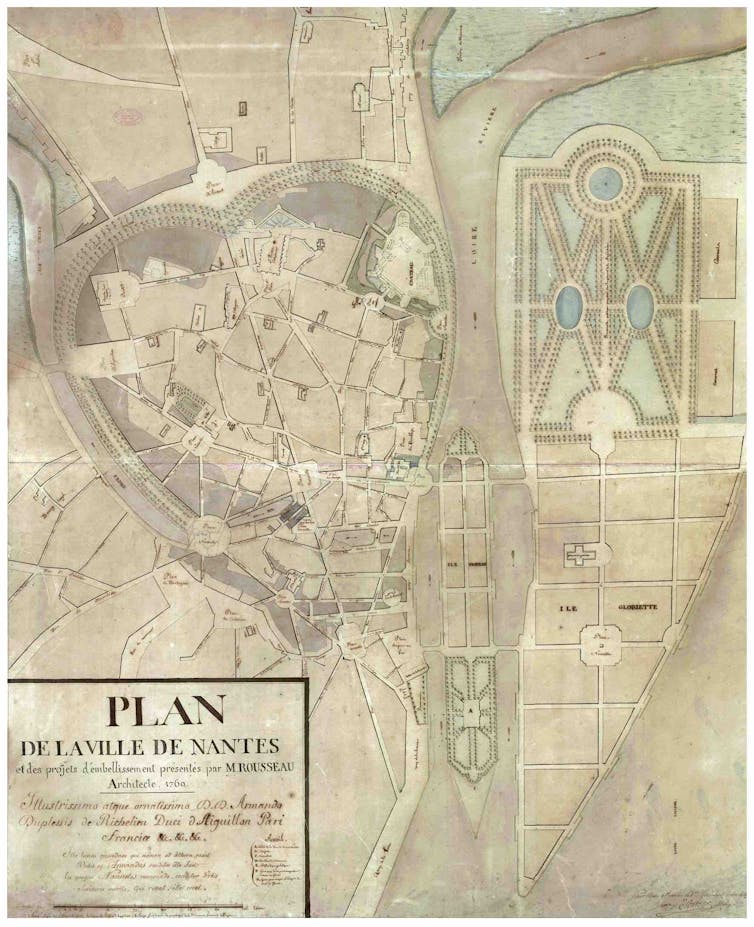

Planning has been inspired by the understanding of one organ in the past. As can be seen in the image below architect Pierre Rousseau designed the French city of Nantes with a centre that functioned as a “heart” and pumped goods and individuals through it.

But, this biological and scientific thinking can also strengthen social divides.

During the 17th-century plagues FlorenceIn Rome and other cities, the poor were seen as lowly organs that attracted, and even bred, disease. As a result, they were locked down in hospitals away from the city – a move medical experts at the time likened to surgical removal of a weak part of the body.

Archives municipales de Nantes

The cells of the city

The scientific discovery of The cellLater, a variety of urban analogies were created in the 20th century.

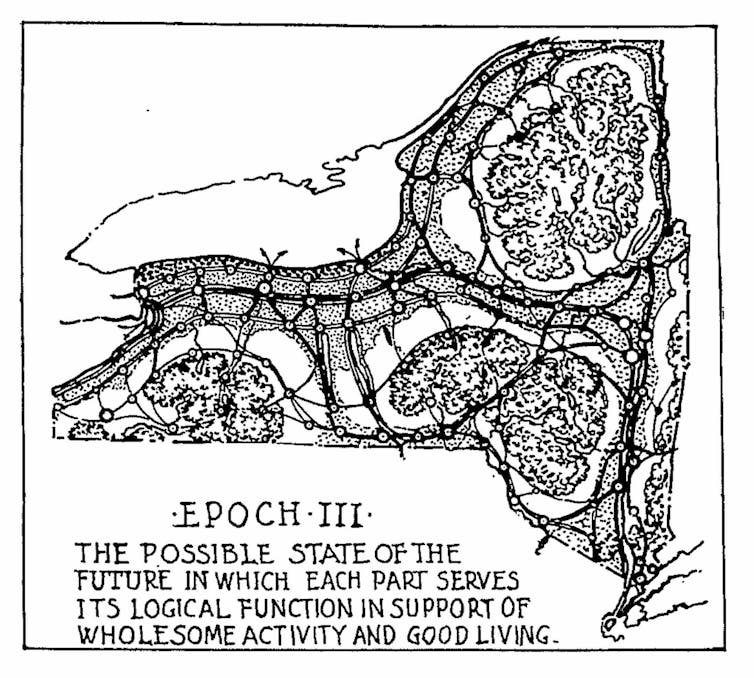

Below is a diagram showing the vision of upstate New York as drawn by community planners Henry Wright in 1926. He envisaged a “tissue” of urban development which fed off clusters of recreational woodland, encouraging wholesome activity and good living for the suburbs’ residents.

Report of New York Commission of Housing and Regional Planning (1926).

Eliel Saarinen, a Finnish-American architect, believed that healthy communities were similar to healthy cells. However, this thought had a flip side.

Saarinen Considered slum areas in cities could be treated similarly to cancers – effectively “excised” by Moving them out of the city centre to “revitalise” the urban centre. This thinking was particularly harmful to the poor and racial minorities.

Continue reading:

Why New Zealand’s push towards greater urban density needs to be seen from the top: New Zealand’s rooftop revolution

New urban naturalism

In a 2017 book, influential physicist Geoffrey WestThe idea is that hidden laws regulate the life cycle of all living things, from animals and plants to cities.

This thinking shows how naturalism is still relevant in 21st-century city planning.

For further examples, we need look only to the concept of the “Smart city”, in which a city’s performance in areas such as public transport flows energy use is carefully monitored. This data can be used to make the city more “intelligent” – improving government services and citizen welfare, and producing indices such as walkscores and liveability.

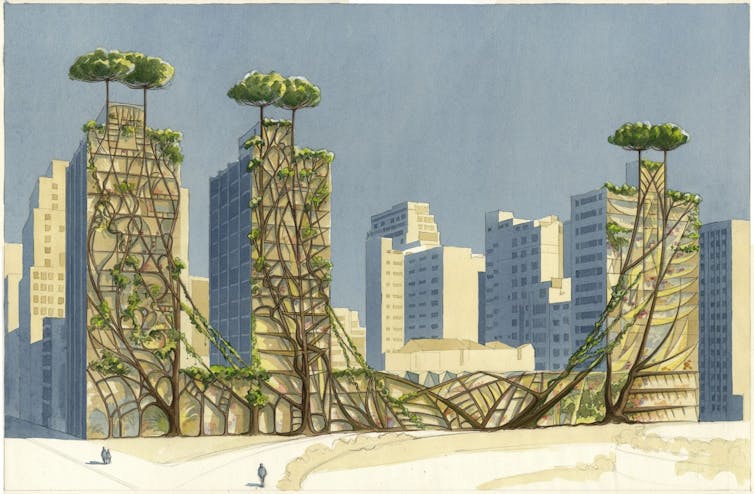

Contemporary Belgian architect Luc Schuiten takes the concept of a living city to its logical extreme in his design for a “vegetative city”.

Schuiten believes that cities should not be built from materials, but products of a healthy local ecosystem. This could be done by first planting a native tree, then building a structure around it.

Schuiten’s idea reflects ancient approaches in cities such the Yemen city of Sana’a, where high rise buildings are made from mud brick – a sustainable material suitable for the city’s hot climate. Schuiten goes further and removes the agency of builders, giving it to plants.

Naturalistic thinking gives us powerful visions of the future. The future city is a good one. However, just like the naturalism of 17th century was dual-edged, so is it now.

The rise of the smart city, for example, promises great benefits for citizens and delivers even greater rewards. Corporations and big tech.

Continue reading:

Smart city or not? You can now see how yours compares

As with any application of science in cities today, naturalistic thinking must ensure that marginalised and disadvantaged people are supported and protected.

COVID-19 offers another reason for urban planning to be more naturalistic. Perhaps seeing the city as a living organism would have left authorities better placed to deal with the pandemic’s spread through urban centres.

A more naturalistic understanding of urbanized people may have made it easier for governments and chief medical officers to make decisions.

Marco Amati is author of the latest book The City and Superorganism: A history of naturalism and urban planning