[ad_1]

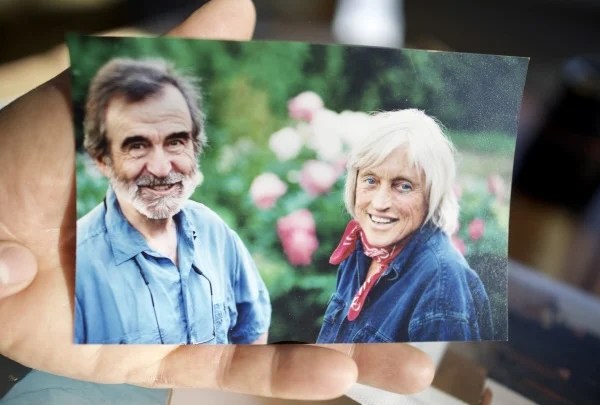

Céline Caron and Yves Tessier devoted their lives to protecting soil health long before regenerative farming became mainstream. Nicolas Lachapelle/National Observer

This story was first published by Canada’s National Observer and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A few handfuls of soil swept to the ground with indifference, was enough to make Céline Caron flinch.

It was June 2013. Caron, a Quebec farmer, environmentalist and one of my father’s closest friends, was enjoying a fresh-picked radish salad outside the house she had shared with her husband, Yves Tessier, for over 40 years. Beside her, on the front seat of a golf cart she used to get around the farm, was a half-teaspoon of dirt that she intended to return to her garden after the day’s heat passed.

A few minutes later, Françis Naud, the septuagenarian couple’s full-time helper, arrived to borrow the cart and swept the dirt aside as he sat on the front seat. Only when Caron’s piercing blue eyes widened in shock did Naud realize his mistake.

“She was hit with a moment of panic to see that the half-teaspoon of soil wouldn’t return to the garden,” he recalled over the phone late last year. “She wanted to bring the soil back to the garden. It was maybe a bit of an intense reaction, but that was her.”

I chuckled: I grew up hearing stories about Caron’s devotion to dirt. She had dedicated her entire life to protecting soil health and microbes and fungi. Every tree or seed planted on the couple’s land was chosen to maximize soil health. They bought very little. They didn’t waste much. Even their food—nearly all homegrown—was chosen with the soil in mind.

They were both ahead and behind their time. For generations, peasant farmers and indigenous people have used judiciously crops and forestry practices to preserve soil health. This is now known as regenerative farming.

In 1971, Caron and Tessier purchased their land. However, most farmers, governments and food companies ignored these old techniques. Farmers were eager to industrialize, and the so-called Green Revolution was well underway. Government policies were geared exclusively towards increasing yields. Pesticides and fertilizers that are toxic have become commonplace, particularly in industrialized countries like Canada. This has caused ecological havoc. Artificial fertilizers have caused huge destruction to farmland, making it infertile, and choking rivers, lakes, oceans, and oceans with toxic algal blooms. Pesticides are partly responsible for the decline in insect populations. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that food production accounts for about 25% of anthropogenic greenhouse gases emissions. This is largely due to nitrogen fertilizers and industrial-scale consumption of meat.

Farmers, scientists, governments and food companies are all interested in regenerative farming because of the crisis. Proponents say rebuilding soil health can reduce or eliminate our need for agricultural chemicals, support insects—natural pollinators and pest control—and store carbon in the ground. Seemingly overnight, Caron’s devotion to soil health seems almost mainstream.

Francis Naud started helping in the couple’s gardens in 2011, and they soon became close. They gave their land to Nature Conservancy of Canada in 2011, but he continues to live on the property as its steward.

Nicolas Lachapelle/National Observer.

I have known this all my lifeCaron and Tessier. My dad was one of the couple’s lifelong friends, having met Caron in his home province of Quebec when he was still in college. They skied together, taking trips in the boreal forest north of Quebec City and Montreal with Tessier or tearing down Mont St-Anne’s mountainside. They remained close over the years, even though he moved to Montreal with my mum shortly before I was born.

They were wise and earthy to me. Patient. Bestowed with understated humor. Wisps of white hair framed Caron’s tanned face and sapphire eyes, which retained a unique magnetism despite her illness. Tessier was a cardiologist and self taught farmer. She was calmer and had a calming smile as well as a easy laugh. His seasoned hands were equally at home in the earth as in the operating room. Both exuded an inner peace worthy to be called the Dalai Lama.

I saw them once a year, during my family’s 1,000-kilometer Christmas pilgrimage back to Quebec. Each year, my parents and their close friends rented a 400-year-old farmhouse in Charlevoix, on the St. Lawrence River’s north shore. Caron and Tessier usually arrived near midday on New Year’s Eve in a battered VW Westfalia van, boxes of their homegrown food and cooking utensils crammed in the back. Every year, we welcomed the couple’s homegrown carrots, beets, garlic, squash soup, and alfalfa sprouts as particularly special gifts.

Céline Caron and Yves Tessier were avid outdoors people and, on top of regenerating their land, went on dozens of expeditions in the Arctic, Himalayas, and other remote parts of the world.

Nicolas Lachapelle/National Observer

“Their gardens were like their children,” explained Renée Frappier, a pioneering Quebec advocate for vegetarian food and one of their longtime friends. “They didn’t have children, so their carrots, their vegetables, were their children, and the soil was their family.”

Because I grew up in Nova Scotia and visited Quebec in winter, the first and only time I saw Caron and Tessier’s farm in bloom was on a searing spring day in 2015. The trees had begun to leaf out, covering their house from the potholed highway with a dense forest of trees and shrubs. The small, grassy clearing just outside their bungalow was home to chickens. A bright orange tractor was parked in the ramshackle tool shed attached to one of the building’s outer walls.

It was like being transported to another place: One wall featured a well-loved wooden counter, cluttered with Mason Jars full beans, flour, spices, and more dry goods. Knives that were worn from decades of sharpening sat in the sink. A wooden bowl held an ulu—they used the traditional half-moon-shaped Inuit knife to mince garlic. Ceiling was lined with wooden frames covered in mosquito net and dried herbs. The solarium at front of the house contained rows upon rows of seedlings. Caron sprouted beans in the bathtub for the chickens—payment, she joked, for the eggs and fertilizer they provided.

Tessier was eager for me to see the farm. I walked beside him as he wrangled his wife’s golf cart up a grassy, tree-lined path towards the gardens. He’d recently been diagnosed with lung cancer and walking in the heat was becoming difficult for him. The forest opened quickly and we followed the hayfield’s edge to an irrigation pond that was hand-built. Beside the road stretched long beds full of vegetables—peas, greens, tomatoes—vines and rows of pear and apple trees. It was feral Pastoralism, an unruly natural dance Caron choreographed into producing food.

Aerial photos of the land taken shortly after the couple moved into it show that the property is mostly covered by fields. The majority of the homestead was covered in vibrant gardens and forests by the time they died.

Nicolas Lachapelle/National Observer

The farm was not always an oasis for nature. As with most parcels of land in this region of Quebec, it was a long, narrow rectangle that extended back from the St. Lawrence. This is a remnant of the colonial land grants French colonizers made to this area of Wendake–Nionwentsio territory. The property was a patchwork consisting of potato fields, sugar bush, and meadows. The soil was thinned by years of overgrazing and haying, as well as pesticide and fertilizer usage.

Photos that Francis showed me last winter from the farm’s early days show them lithe, strong, in love, and determined to transform their land into a biological haven. They had created a forest that was home to more than 50 species of vegetables and dozens of fruit trees. The forest was also filled with walnut trees and maple trees by the time they passed away 40 years later.

Karen Ferland, one of the couple’s former interns, recalled that Caron had an uncanny ability to work harmoniously with nature. Although she had not been trained in agriculture, Caron learned by working with researchers, reading hours every day, and taking note of nature. Caron was happiest outside, even if it meant putting on her Arctic parka to spend hours on cold midwinter days.

Through journals, the draft of Caron’s unpublished book and even their will, the couple charted how they tried to preserve biodiversity-friendly plants like milkweed — the endangered monarch butterfly’s favorite food — and regenerate the land by planting thousands of trees. They created a garden with enough greens and sunflowers to keep the birds happy, and also tended grapevines and apple and pear trees. These varieties were not grown in Quebec at that time. It is a region where winter temperatures can drop below -30 C.

Francis Naud has a small flock that includes turkeys and chickens. These birds provide eggs, meat, fertilizer, and are well-suited to regenerative agriculture.

Nicolas Lachapelle/National Observer

Caron used a number of regenerative methods at a time in which conventional farmers were not willing to use them. To fix nitrogen and keep fallow fields cultivated year-round, she planted clover and alfalfa cover crops. This was an unusual technique at the time but is now supported by the federal government and many traditional farmers. She kept chickens, goats and other animals for their manure, but also because they helped aerate the soil and provided food — an approach backed by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Like modern regenerative farmers, her goal was to preserve soil health.

However, the gardens paled in comparison to the forest they planted back on their land. Growing up, my dad told stories about the forest from a field, but I didn’t realize its scale—huge —or why Caron cared so much for trees until recently. She believed forests were essential for healthy soils as they foster vibrant soil ecosystems and increase the nutrients available to crops. She spent many years working with Gilles Lemieux (Laval University forestry professor), to determine if rameal fractured wood, or wood chips made of the nutrient rich tips of deciduous trees, could be used to regenerate land.

The experiments worked. As a people-lover, she was eager to share her knowledge at farming conferences in Quebec and elsewhere. And every year for decades, she would join Tessier and a crew of friends and family to collect scrub branches Hydro-Québec cut back on a powerline right-of-way that cut across the couple’s land.

Their regenerative resource was wood, left to rot in the hands of a power utility.