[ad_1]

Tuvalu’s Minister of Justice Simon Kofe made headlines during COP26 this past November by addressing the UN climate conference while standing knee-deep in seawater.

“We are sinking,” he said, highlighting the existential danger that climate change fuelled sea-level rise represents to the world’s low-lying island nations.

The viral video from Tuvalu was made. The image, which was similar to those from Fiji and Kiribati in the Pacific Islands, showed entire towns being moved further inland while villages succumb to the waves.

PIN IT

PIN ITMinistry of Justice, Communication and Foreign Affairs, Tuvalu Government

Simon Kofe (Tuvaluan politician) speaks on behalf Tuvalu in a prerecorded audio for COP26.

A similarly troubling, but much less eye-catching tragedy is occurring on the opposite side of the globe: The Arctic, where rising temperatures are shrinking ancient glaciers, thinning sea ice, and warming and thawing the planet’s permafrost.

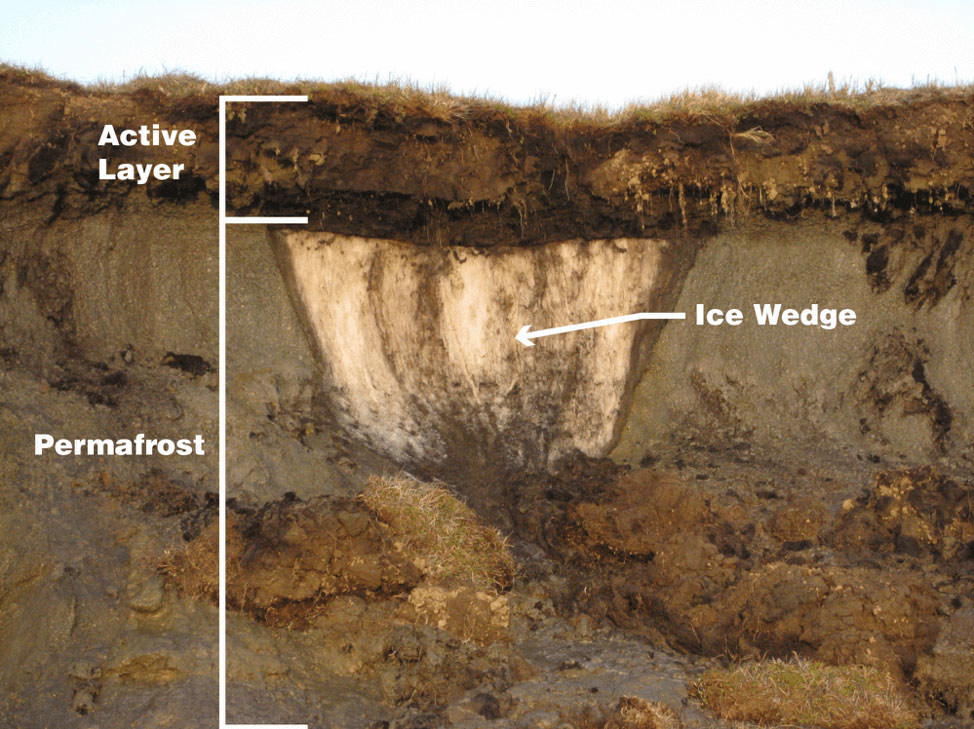

Permafrost is ground below the Earth’s surface that has been continuously frozen for at least two consecutive years and in most cases, for hundreds or thousands of years. It covers about a quarter the Northern Hemisphere. Not You are covered in snow

This frozen ground lies beneath large areas of Alaska, Canada, and Siberia. It is where many people, mostly indigenous, have lived, worked and hunted for hundreds upon hundreds of years.

Climate change is causing displacement

PIN IT

PIN IT© Eriel Lugt

Eriel Lugt, an Inuit young activist, Tuktoyaktuk’s coast that has been eroding since years due to permafrost.

“In my future and our youth’s future, I picture our community being completely relocated,” Eriel Lugt, a 19-year-old Inuit indigenous activist from Canada’s Arctic region, tells UN News.

Although the images of polar bears in distress trying to adapt to the changes in the Arctic landscape are still ingrained in our minds, the idea of entire human settlements being relocated and indigenous communities having to rethink how they live is not something we hear about.

“When I first learned about climate, I was in grade 9 and I hadn’t realized that climate change was happening so rapidly in my own community, Right in front of me”.

Indeed, Tuktoyaktuk has suffered for years from the effects of our melting cryosphere.

“Here in Tuk our whole land is on permafrost,” she explains, “The thawing is completely changing our land structure, and with that our wildlife is also being affected.”

The melting of this Frosted ground below the surfaceThis covers approximately 9 million square miles of the north side of our planetAlthough it is not visible from the outside, its effects are very real. Roads, houses and pipelines, as well as military facilities, are all collapsing or becoming unstable.

Permafrost is a hardier than concrete and is the basis of many northern villages like Tuktoyaktuk. But as the planet rapidly warms – the Arctic at least twice as fast as other regions – the thawing ground erodes and can trigger landslides.

Furthermore, storm surges can be made more difficult by the loss and change in sea ice.

“Our community is known for having fierce winds, and every summer there would be days when the wind just makes the sea level rise, so that’s another problem we face… Each winter I notice still that the coast loses about an inch of land,” Eriel highlights.

Some of her neighbors, who lived in the tundra above the beaches, were forced to move inland.

“The ground was basically caving in under their houses,” she said.

© US Geological Survey/NASA

Layers of Permafrost.

Consequences on human access to water and health

Susan M. Natali, a scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center*She has been studying Arctic permafrost melting for more than 13 years.

“I can see the changes, it’s devastating. I don’t even know if I can communicate the magnitude of how this is impacting people. They literally have to prop up and raise (from the collapsing ground). This is something they might have done in the past maybe once a year, and now they’re doing it five times a year because their houses are tilting,” she describes.

Dr. Natali explains how the melting permafrost causes fuel storage units to collapsing. She also notes that landfills once located in dry areas are now leaking waste, toxic materials, such as mercury, into rivers and lagoons.

“Rivers are where people get their water and their fish, so there are human health impacts… The thawing it is also causing some rivers to sink making it harder to access clean water,” she adds.

Another problem is that many communities move across the land in the winter using frozen rivers and lakes that are not “freezing” enough anymore.

“This is not only a health risk, but it is also impacting people’s accessibility to food. There are so many things going on… this is a multifaceted problem impacting both natural systems and social systems… This is something that is a reality now for people who are living in the Arctic, and it’s been a reality for a long time.”

PIN IT

PIN IT© Chris Linder

Dr. Susan Natali, a scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Centre studies permafrost from the Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta area of Alaska.

Wildlife and humans

Eriel Lugt is no stranger to the scientist’s affirmations, her people have been on their land for hundreds of years, knowing where to hunt and how to travel, but now they are being forced to adapt.

“The ancestors taught generations and generations where we need to go while travelling, like which routes of the ice and land are safe to go by. With the climate changing, the land has become dangerous because our hunters are not so sure anymore what’s the safest route to take.”

Not only the Inuit have to learn how adapt, but so do other communities.

Dr. Martin Sommerkorn (coordinating lead author of Polar Regions Chapter of The Harvard Encyclopedia of Science and Technology) said that IPCC Special Report on Oceans and CryosphereHead of Conservation, Artic Program at WWF. Animal habitats and living conditions are also being changed.

“The Arctic is going to warm two to three times as much as the global average over the course of this century. So, when we’re talking about 1.5C degrees globally, we’re talking about 3 degrees in the Arctic”, he explains.

This means more frequent heatwaves during both winter and summer, with some of what he calls ‘indirect effects” already happening.

“Heatwaves lead to wildfires and insect outbreaks on land and together this weakens the ecosystems, and they basically burn. They are more vulnerable to insect outbreaks that can cause defoliation, which has cascading effects throughout the ecosystem., making it very difficult for the Arctic species to exist in these places,” Dr. Sommerkorn adds.

According to the expert, however, there isn’t an immediate extinction in Arctic species in many locations because, like some human settlements they are moving further north to escape climate change.

“We are seeing desperate accounts of wildlife. Caribou, for example, are fleeing the summer heat and wildfires. On the sea, we are witnessing a complete takeover by boreal fish community of previously Arctic marine ecosystems. There are impacts that you can see anytime you are up there.”

Dr. Sommerkorn adds that however, the northward migration of species, or in biological terms “range shifts”, has some hard limits in places such as Siberia, where are very few islands north of the coastline.

Why bother? The global impacts

Why should the whole world care about the Artic? Dr. Natali explains how what is happening in the Artic impacts the future of the planet.

“There’s so much carbon stored in permafrost, and it’s frozen now. It’s locked away, and when that thaws, it then becomes vulnerable for being released into the atmosphere to exacerbate global climate change,” she tells UN News.

Plant and animal material frozen in permafrost – called organic carbon – does not decompose or rot away. As the permafrost begins to thaw, microbes begin to break down the material and release greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide or methane into atmosphere.

“It just sort of turns into this organic soil that’s been building up for thousands and thousands of years so it’s a carbon pool that’s out. It’s not part of our active carbon cycling…It’s a fossil carbon pool that it hasn’t been part of our earth system for many thousands of years,” Dr. Natali emphasizes.

Dr. Sommerkorn also stated that permafrost could represent the emissions from a medium-sized nation even under low levels global warming.

“And they could grow much more… that is what we know. What we don’t know is how much of that will be compensated on-site. So how many new plants will be able to grow on permafrost soils now? How do you get that carbon back in? But these emissions will be coming,” he explains.

PIN IT

PIN ITCIFOR/Nanang Sujana

Peatland forests such as this one in central Kalimantan (Indonesia) can store harmful carbon dioxide gases.

He gives an example of peatlands, which are located in Scotland, as the latest example. UN Climate Conference, COP26A country that works to reduce its emissions more than 50% before 2030.

Peatlands are Terrestrial wetland ecologiesWhen plant material is not fully decomposing and is prevented from releasing carbon by waterlogged conditions.

“They are fighting big time and don’t have a solution yet for the legacy emissions from drained peatlands that were made available for farming and forestry. Once you drain them it’s basically what will happen to permafrost soils once they start thawing deeper in many places: you just commit to centuries of emissions and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Right now, emissions coming from peatlands drained decades ago are almost one-fifth (18 per cent) of Scotland’s emissions. These vital carbon sinks are now being restored.

“It is a strong and steady contribution at a time when we are desperately trying to keep within our atmospheric budget for Scotland… permafrost carbon will (also) come at a very, very inconvenient time to us.”

But unlike drained peatlands, thawing permafrost cannot be reversed in a human’s lifetime while the global temperature keeps increasing.

Also, permafrost thaws and ancient bacteria and viruses in the soil and ice also thaw. These microorganisms may make animals and people very sick.

NASA claims that scientists have found microbes older than 400,000 years in thawed Permafrost.

The need for science and adaption

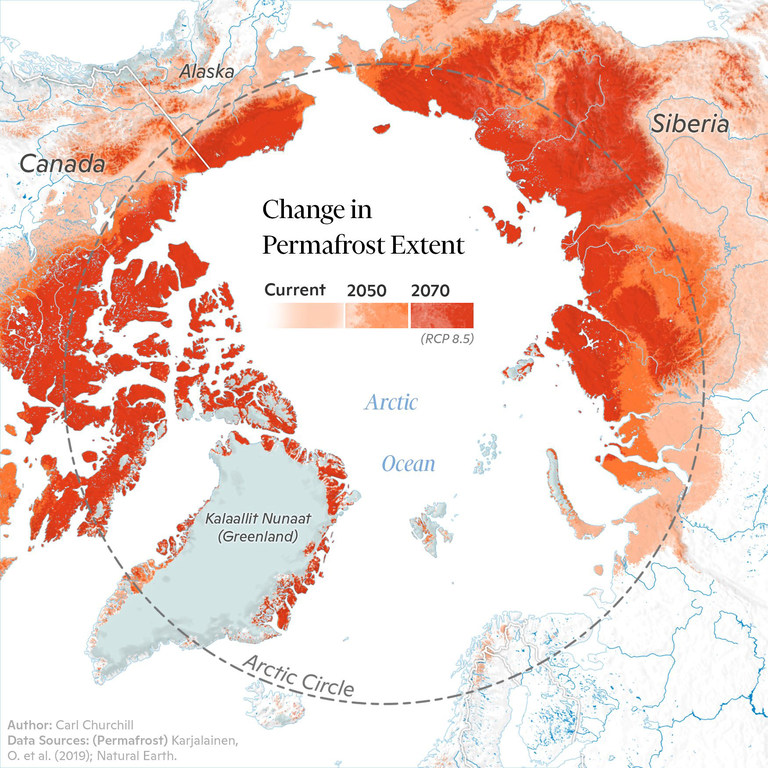

Carl Churchill/ Woodwell Research Center

Changes in the permafrost map.

In 2019, the United Nations Environmental Programme was reintroduced (UNEP) called the thawing of permafrost One of the top 10 emerging environmental concerns. The Artic’s southern permafrost borders had receded northwards by between 30 and 80 km, a significant loss of coverage.

UNEP supported a study in 2020 on Rapid Response to Permafrost Rapid Response in Offshore and Coastal Areas, where residents from Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk participated in the western Canadian Arctic.

Hundreds of people attended a call for a community science day in “Tuk.” The study concluded that people living along the Arctic coast generally appreciate the efforts of the scientific community to better understand permafrost processes and change.

They have not been involved in the provision of logistic support or science, and they have not been involved in guiding scientific research toward issues that are important for Arctic peoples.

UNEP called for the incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge regarding coastal environments and processes in research programs wherever possible.

“It’s amazing to me how people are dealing with this. Because you know, there’s not a support system. I can only speak on behalf of the United States. There isn’t a support system for climate change adaptation. It’s almost as if climate change is happening faster than science can keep up and happening faster than policy can keep up. There are people dealing with this almost on their own and piecing together support to deal with this, there’s no governance framework,” highlights Dr. Natali, who recently testified on the issue before the US Congress.

Newtok, an Alaskan village, was one of the first North American communities to be affected by climate change.

The Yup’ik tribe of Yup’iks have seen their village crumble due to thawing permafrost. Water took over, and they were forced to move.

Since 2019, they have been gradually relocated to Mertarvik which is nine miles away.

Visibility issues

Meanwhile in Canada, in September 2021, Tuktoyaktuk residents were told that protecting their town from climate change would cost at least $42 million and that any such protective measures could only be “guaranteed” to last until 2052.

Engineers have explored a variety of options to adapt to the changing climate. One option is to put down layers of Styrofoam insulation or geotextile to protect permafrost from rising temperature.

Tuktoyaktuk’s surface is being eroded at an average rate 2m per year. If mitigation is not taken, the island will disappear at the current rate. Similar fates could also befall Siberian and North American communities.

Eriel Lugt, her people, and others know this. Since two years, she has been part of a climate monitoring project. This involves collecting samples from the ground and registering any changes.

“I personally think that If enough people in the world were to be aware of the dire consequences of climate change, and leaders would acknowledge it more, then this issue could be addressed.”

Ms. Lugt was joined by three young Inuit activists who had the opportunity tell the story about how their community is dealing with a changing environment during COP25 Madrid in December 2020.

They shared a trailer together It’s Happening to UsA movie they made together with their Community Corporation and Canadian filmmakers.

Is there a solution?

Dr. Natali explains that while we can’t now reverse permafrost thaw – because it has already started – ambition is key to avoid the worst of it.

“I believe that even in the most ambitious of scenarios (for reducing global carbon emission and subsequent warming), we will still lose. About 25% of the surface permafrostThe atmosphere will then get some of the carbon in there. This is better than less ambitious scenarios that could lead to a 75 percent thaw. Permafrost is a climate change multiplier and so it needs to be an ambition multiplier,”She emphasizes.

Dr. Sommerkorn says that there is not enough knowledge of the long-term consequences of changes in the cryosphere (frozen components of the earth) at the decision-making level.

“These changes have a direct link to the ambitions for 2030. The IPCCIt was clear: If we want to keep the temperature below 1.5C (warming), we must reduce emissions by 50% by 2030 compared with 2010. cryosphere doesn’t grant us the luxury of overshoot… We will set off thresholds of melting that can’t be reversed. It is very difficult to regrow glaciers. It is basically impossible to grow back permafrost under raising temperatures”.

The expert explained that by reducing emissions and the rate of heating, we are also reducing melting and sea level rising, and giving people the time and tools to adapt.

“We have to urgently make decisions now when we plan for infrastructure, cities etc., and we can in parts of the world that have technical help and the funding…others need global help in adaptation funding,” Dr. Sommerkorn adds.

The urgent call to world leaders for action

The Head of Conservation at the WWF was one of a group that included scientists and mountain communities, who called for leaders at COP26 attention to the dire global consequences of glacier and icesheet loss.

“For too long, our planet’s frozen elements have been absent from the climate debate at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) even though their crucial role in determining the future for more than a billion people and our climate is becoming even more clear,” he said at the time, asking the COP organizers to create a dedicated space to discuss actions to be taken in response of the cryosphere crisis.

Dr. Natali, a permafrost expert says that if you don’t incorporate important Earth system feedback like greenhouse gases resulting in frozen ground thaw it makes it difficult to reach the 1.5C target. Paris AgreementIt is almost impossible.

We’re not even doing the math right Permafrost isn’t properly and fully accounted for in the bookkeeping

“It’s a big enough challenge to get nations to make the commitments and take action. But imagine that we’re not even aiming for the right target, which is essentially what’s happening right now because we’re not even doing the math right, Permafrost isn’t properly and fully accounted for in the bookkeeping, and because people aren’t thinking about it,”She warns.

She says that although it is impossible to control the emissions from permafrost in ground, it is possible to get the science to the right place and make that information available to policymakers and the public.

“Actions we take elsewhere have a multiplying effect, right? The more we reduce fossil fuel emissions, the more we protect forests… this way we are also, in turn, reducing the emissions that will come out of permafrost and the impact on northern communities,” she says.

There is no need to be an early warning

Scientists ask that a special day be set aside for UN climate talks, at COP27, to allow for a dedicated dialogue on the cryosphere with leaders about the consequences and impacts of the changing landscape.

“It is not enough to look at previous IPCC reports and to carry over our understanding that the melting of cryosphere and its effects in the polar regions are an early warning signal.No, there is no early warning signal at this point. they are driving climate change and impacts globally,” Dr. Sommerkorn highlights.

The expert noted that the preamble for the COP26 final result text reads: We must ensure the integrity of ecosystems, including the cryosphere.

“Just saying that is already showing that the matter has not been fully taken into account and fully understood, so we will be asking for such communication to go forward,” he adds.

Dr. Sommerkorn felt that Glasgow had given the world greater potential to contribute through the Paris Agreement. He believes this forward momentum should help achieve the 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

“I think the happy message here is that it is actually in our hands. At COP26 we made some significant progress on global governance. It’s not all disastrous, but We need to find ways to make that a reality and take immediate action.. And that’s the key to the cryosphere crisis”.

*Woodwell scientists helped to launch the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992 and shared the Nobel Prize with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007.