[ad_1]

China’s electricity system would need to reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 if the country is to meet its recently announced target of “carbon neutrality” before 2060.

This is one of the key insights from new scenarios and policy recommendations for meeting the goal, published separately by two leading – and highly influential – Chinese climate research institutes.

The scenarios hint at the thinking behind Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s announcement and offer a glimpse of what it might mean for the energy system in China – and the world. China accounts for almost 30% of the world’s CO2 emissions, more than half of its coal use and half of coal-fired power capacity.

上微信关注《碳简报》

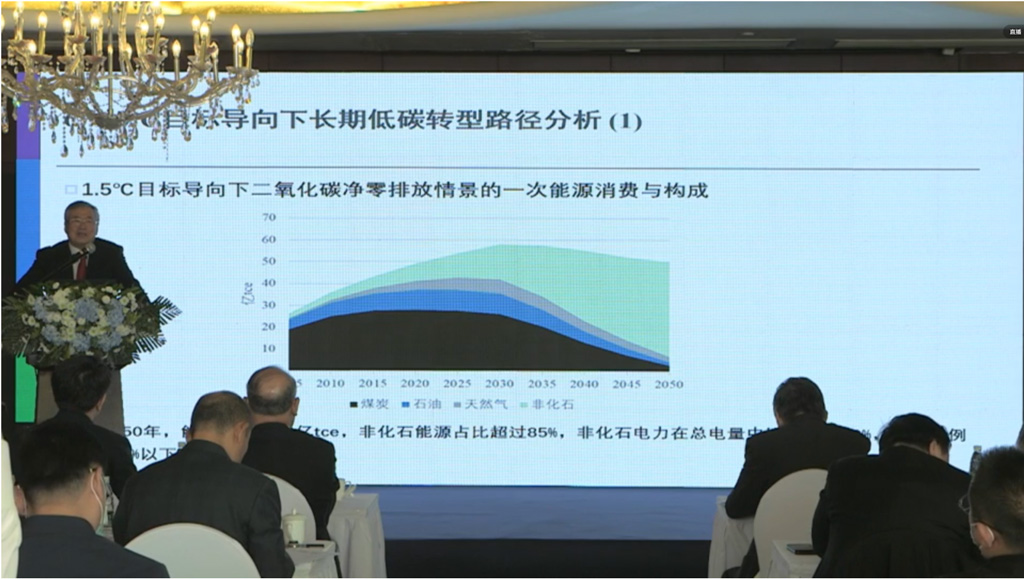

Both scenarios come close to phasing out fossil fuels, with more than 85% of all energy and more than 90% of electricity coming from non-fossil sources – renewables and nuclear – by 2050.

The energy pathways discovered since the goal was set announced on 22 September show how the thinking on China’s future energy system is already shifting, but also highlight some of the questions that are still left open by the one-sentence announcement, where, according to the official translation, Xi said: “We aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.”

New scenarios

The Tsinghua University Institute for Climate Change and Sustainable Development, along with 18 other Chinese research institutions, is the first of these new scenarios. released their “China Low-Carbon Development Strategy and Transformation Pathways” (presentationEnglish, 12 October.

Meanwhile, Prof Zhang Xiliang of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment and EconomyRecent presentation by Tsinghua 3Ein ChineseStarting at 3:46, this article examines the energy- and economic implications of reaching zero carbon emissions by 2050 or 2060. This appears to have informed the 2060 goal date.

Both scenarios indicate that the electricity sector would need to get to zero emissions by 2050 and start delivering “negative emissions” thereafter – assumed to come from bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) – to offset hard-to-eliminate emissions from industrial processes, agriculture and other sectors.

Tsinghua 3E envisions power generation from coal ending in 2050. However, it retains significant coal use outside of the power sector until 2060. The ICCSD scenario already sees coal as a smaller percentage of the overall energy mix than it was in 2050.

The phasing out of fossil fuels means that more than 85% of all energy and more than 90% of electricity should come from non-fossil energy – renewables and nuclear – by 2050.

Tsinghua University’s Prof He Jiankun presenting the evolution of China’s total energy demand and energy mix under the 1.5C emission pathway at the release event of the “China Low-Carbon Development Strategy and Transformation Pathways” on 12 October (black: coal, grey: oil, light blue: fossil gas, green: non-fossil energy). Source: Screen capture from Tsinghua’s presentation live-stream.

Higher ambition

The announcement of 2060 clearly opens up the possibility for more ambitious energy plans. This is apparent when comparing the current scenarios towards 2060 with previous projections.

For example, last year’s China Renewable Energy Outlook 2019By the National Renewable Energy Center – a thinktank under China’s top economic planning ministry the NDRC – saw non-fossil energy reaching only 65% in 2050. This annual report is a bullish argument for renewables.

In the new scenarios, the main strategy for phasing out fossil fuels outside of the power sector is electrification, which means that emissions-free power generation will need to replace not only China’s coal-fired power plants – half of the world’s total – but also much of the coal and oil consumption in industry, transport and heating sectors.

Delivering the energy needs of the world’s largest energy consuming economy from non-fossil sources appears a huge undertaking.

Based on Tsinghua 3E’s work, it means growing China’s solar power capacity about 10-fold and wind and nuclear power capacity seven-fold by 2050. China would then have more than four-times the solar power capacity and three-times the wind power capacity of the entire world, while nuclear power capacity would be at 80%.

The striking thing about these scenarios is the fact that the actual increases in clean energy uptake rates are very modest considering the scale of the industry in China.

It would take almost two times as many solar and wind power plants to double, while nuclear energy would need to double between 2020-2050 and 2016-2020.

Tsinghua 3E projects total energy consumption to peak by 2035. Then, clean energy growth would completely replace existing fossil fuel use. This would be contrary to the current dynamic, where emissions are increasing despite the growing share of clean energy. This is due to rapid growth of overall energy demand.

In the ICCSD scenario, which is expected to be in line for a global temperature target at 2C, electrification is emphasized. Essentially all energy-sector investments go towards electricity.

Both sets of scenarios find that getting to a 1.5C compatible pathway – and to carbon neutrality – requires significant investment in negative emissionsThey plan to realize this with biomass CCS (BECCS) in the power sector.

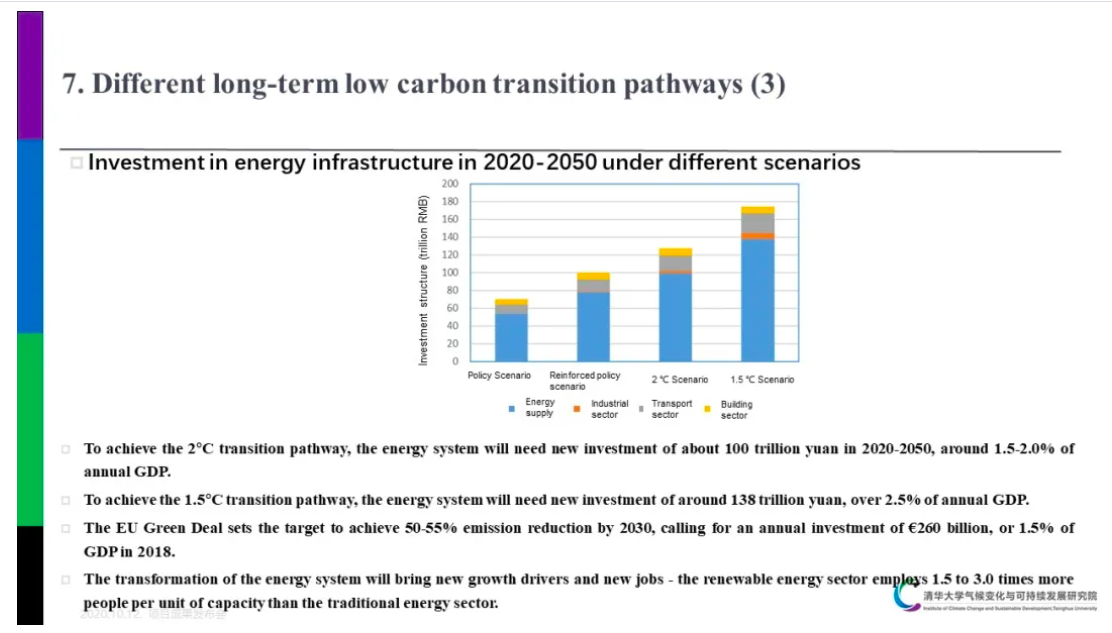

The ICCSD 2C scenario requires investment of RMB100tn ($15tn) between 2020 and 2050, This is 1.5-2.0% of China’s GDP over the period, which the researchers argue is similar to the investment required in the EU to meet a target of reducing emissions by 50-55% by 2030. In the 1.5C pathway, the required investment is RMB140tn ($21tn).

A slide from the ICCSD presentation where energy infrastructure investment under different emission pathways is compared to investment required under the EU’s 2030 emissions goals in terms of ratio to total GDP. Columns left-to-right: Current policies; strengthened Nationally Determined Contribution, 2C emission pathway, and 1.5C emission path (Orange: electricity; blue: carbon capture & storage (CCS), yellow; oil; gray: gas. Source: ICCSD.

Crucial details

The importance of certain details that remain unresolved in the comparison of the different projections is also highlighted by the comparison of them.

There are many assumptions about the emissions included in the pledge, and how much CO2 is involved. taken up by ecosystemsThe result is a wide range in energy-sector emissions budgets.

As highlighted by, optimistic assumptions about CO2 removal through afforestation will leave more room for fossil-fuel emissions. remarksAn environment ministry researcher.

Another important question is whether the target includes only CO2 or all greenhouse gases (GHGs). If the former is true, then energy sector emissions would need to fall faster and more quickly. Some of the GHGs that are hard to eliminate are difficult to eliminate.

The ICCSD scenario seems to be the most ambitious of all the projections. This may be because the researchers interpreted this target as including all greenhouse gas emissions.

But, according China Dialogue, which cites “one expert close to China’s policy on non-CO2 greenhouse gases”, this interpretation remains an assumption by the researchers at ICCSD rather than an official government position.

Challenges

The Chinese economic model excels at mobilising large amounts investment. This means that scaling up clean technology, electrified transport, and other new technologies may not be the greatest challenge to reaching carbon neutrality in 2060.

Instead, the country will need to manage the economic, political, and regional impacts of phasing off fossil fuels.

By 2050, in the ICCSD low-carbon development pathway, coal would supply less than 5% of China’s energy – and much less than 10% in the power sector. This would result in the closing of all but a few coal-fired power plants and 5,000 coal mines currently operating in China.

Coal-fired power stations would shut down at an average of 30 years old. This is in line with the experience so far in China – more than half of the capacity built in any year before 1990 has retired already, indicating an average plant life of 30 years. For any new projects that are permitted this year, or in the future, 2050 is approaching.

A demonstration of the challenge was seen when China’s coal consumption and CO2 emissions started to fall in 2013 to 2015, as the effect of stimulus measures wore out.

The leadership’s initial response was to brand the development as a part of a transition to a new economic model – the “New Normal”. In 2015, however financial distress was erupting at state-owned mines and smokestack industries enterprises. The government responded by providing additional stimulus to these companies, rather than putting them through restructuring.

The impact on countries that depend on fossil-fuel imports might be more dramatic for those economies. China’s new economic policy of “dual circulation” (reducing its reliance on overseas markets and technologies) and new emphasis on energy security mean ever greater efforts to replace imports with domestic supply.

This, combined with the pledge to reduce fossil fuel demand by carbon neutrality, is also a significant factor in heavy investmentThis could lead to a rapid exit from fossil fuel imports in domestic coal, oil, and gas production and transportation.

It is also clear that realising the carbon-neutrality vision will require work on deep decarbonisation options in sectors that are currently viewed as “hard to address”, particularly steel, cement and chemical industry process emissions, as well as agriculture and aviation.

These initial studies assume that BECCS will be a more cost-effective solution than decarbonising these areas. However, there could be other affordable mitigation options.

The ICCSD’s main report will be followed by 17 sectoral reports that will explore the potential solutions. ICCSD’s policy recommendations and the environment ministry’s statementThe 2060 target calls for key industrial sectors in order to peak emissions during the next five years (2021-25) of the five-year plan.

Ambition gap

ICCSD also gives recommendations for upgrading China’s commitments under the Paris Agreement. The recommendations include committing to no further CO2 emission growth from 2025 onwards, one step short of an emissions “peak”.

This would mean that total emissions should be limited to 10.5 billion tonnes. The institute also recommends increasing China’s non-fossil energy target to 20% by 2025 and 25% by 2030 (from 15.3% in 2015).

It also says the five-year plan’s targets for 2025 should include peaking coal consumption and strictly controlling new coal power capacity.

One proposal that could be important for the next five years is to set CO2 peaking targets in key cities and industrial sectors that are energy-intensive, to allow the national peak later.

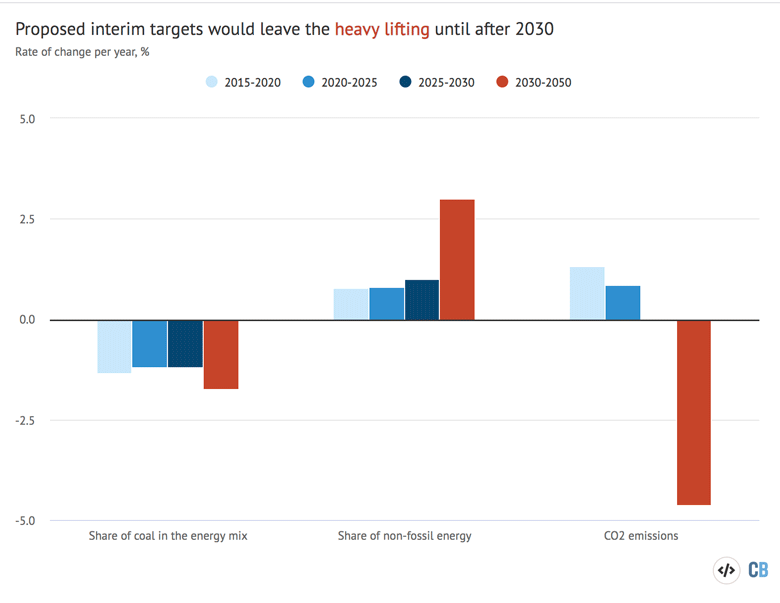

However, the proposed limit on CO2 emissions would still cause an increase of 4% in CO2 emissions from 2020 to 2025, which is almost 1% per year. The researchers recognise that continued increases in CO2 emissions from China are not in line with the 1.5C or 2C targets, but argue that “inertia” in the system means the country will fall behind those goals and will have to catch up later.

Under the Tsinghua proposals of 20% non-fossil energy in 2025 and 25% in 2030, non-fossil energy would be increasing at the same rate as China has to date – about 1 percentage point per year. Then, during the 2030-2050 period non-fossil fuel energy would have to grow three times as fast at three percentage points per annum.

Similar to the above, the growth of CO2 emissions would slow slightly from 1.5% per annum in 2015-2020 down to 1% in 2020-25. Then it would stop in 2025-30. To reach net-zero in 2060, the emissions would need to decrease by approximately 4% per annum.

Therefore, adapting China’s near-term targets, policies and commitments to the long-term goal will remain challenging – or else the bulk of the effort required to reach carbon neutrality will be left for the following decades, as shown in the chart below.

The ICCSD’s recommendations for 2025 and 2030 were translated into annual rates and compared with the rates achieved in 2015 to 2020 during the current five-year plan period. Source: Author’s analysis of ICCSD scenario and historical data. Carbon Brief Chart Highcharts.

All eyes on China

Presenting ICCSD’s findings, Prof He Jiankun, chair of the ICCSD academic committee and deputy director of China’s Advisory Committee on Climate, noted that China’s 14th five-year plan is attracting a lot of attention internationally as the country’s success in controlling Covid-19 is allowing the economic recovery to start earlier than other countries.

Xi Jinping also has emphasisedThe importance of a green recovery following the crisis. If this green recovery is translated into domestic policies, it could accelerate the country’s transition to carbon neutrality. [Carbon Brief is tracking how governments around the world are introducing “green recovery” stimulus measures.

Receive our free Daily Briefing for a digest of the past 24 hours of climate and energy media coverage, or our Weekly Briefing for a round-up of our content from the past seven days. Just enter your email below:

There is also the possibility that the energy targets for the upcoming five-year plan could be revised after Xi’s announcement to reflect the increased long-term ambition. While the plan is only due to be published in 2021, the drafting process had been gravitating towards targets that are close to what the Tsinghua researchers proposed.

Research on cost-optimised emissions reduction strategies suggests that a more linear path towards the 2060 target would be economically optimal (see e.g. IPCC special report on 1.5 degrees), not to mention more credible to the outside world. Furthermore, targets championed by Xi personally tend to be overachieved by the government and wider bureaucracy.

Therefore, there are multiple factors that could lead to a faster shift in emissions trends, as different parts of the economic planning machinery, local governments and state-owned enterprises chart their own pathways to realising the overall 2060 vision.

Sharelines from this story

[ad_2]

Source link