[ad_1]

Many of us are trying to balance the marrow-deep need for a child against the realization that as they grow up, a warming planet will fuel food shortages, social divide, and wars.

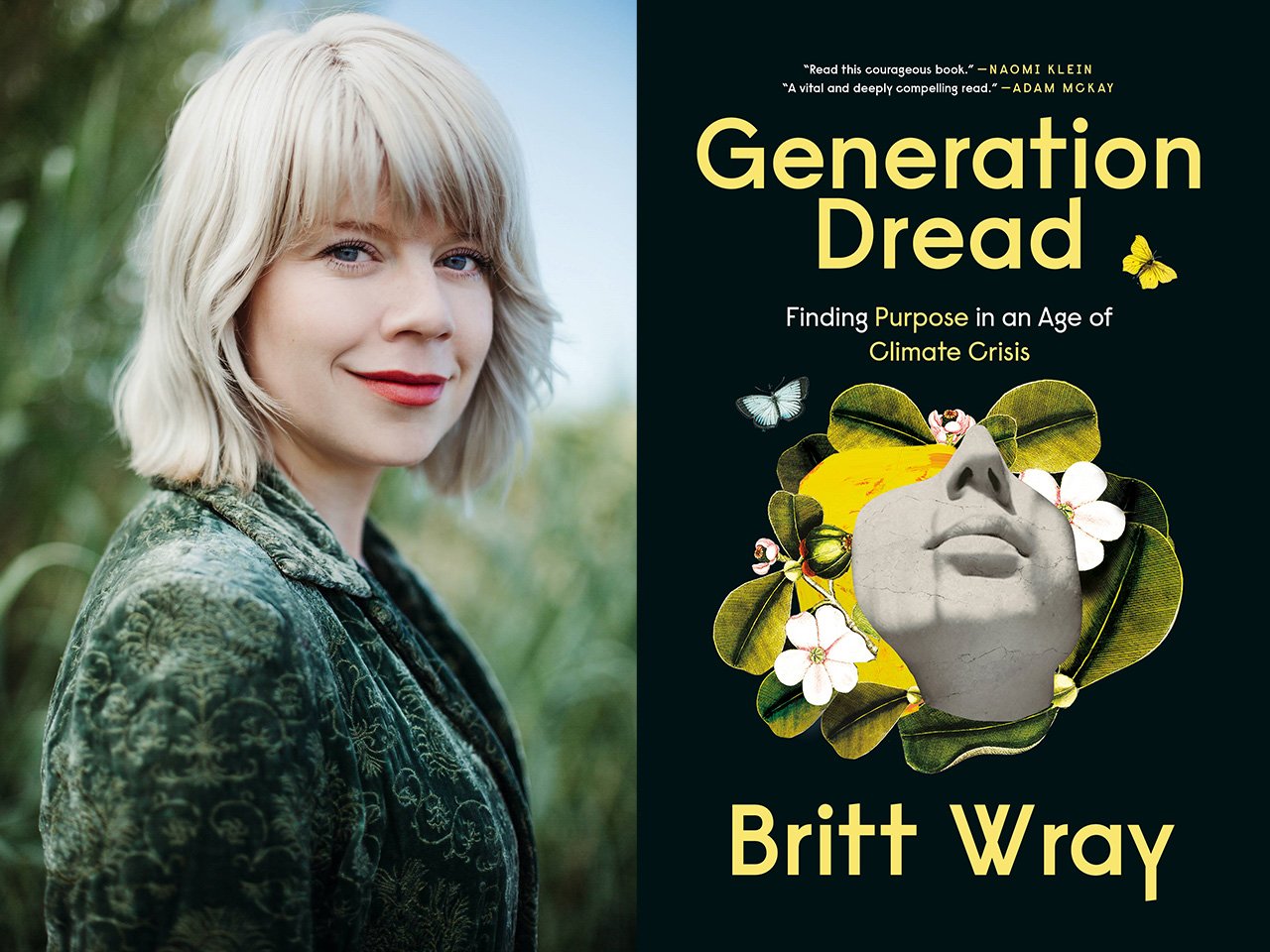

(Photo: Arden Wiray, courtesy Penguin Random House

Back in 1986, when they got pregnant with me, my parents were having very different conversations from the ones I’m having with my partner now. I wore lace to their wedding that year, draped in my mother’s elegant maternity gown. In keeping with the boom times, my father wore an ivory pinned-tripe suit and fedora. At the end of the decade, consumerism, privatization and free markets would spread like wildfire. The world was flooded with unregulated capitalism.

In 1988, my hometown of Toronto hosted the world’s first intergovernmental meeting to discuss climate change and the need for governments, the UN, industry, NGOs, educational institutions, and individuals “to take specific actions to reduce the impending crisis caused by the pollution of the atmosphere.” I was not yet two years old. If leaders from high-emitting nations had taken the message seriously and begun lowering their emissions, we could have slowly reduced the pollution by a few percentage points per year. Naomi Klein describes this step that no one took as “a very moderate, gradual, centrist type of phaseout.”

Instead, our emissions have been increasing steadily since that meeting. The UN says we must reduce our emissions by half by 2030 if we want to avoid irreversible climate disaster. However, the world has already warmed by about 1.2 C since preindustrial times. Our current trajectory suggests that we could reach 1.5 C by 2030. My reproductive window will be almost closed by then and the ticking in my brain will drown out all other daily thoughts. Two clocks are in sync, one for biological and one for planetary. Both alarms are set to light the world on fire.

As I write this, I’m 33, the same age my mom was when she had me, and there are plenty of reasons why the decision to reproduce is different now than it was for her: the disappearance of job security, the creeping disintegration of many democracies, and the fact that my generation is the first in modern history not to do better than our parents. As a well-known environmentalist Bill McKibben made it part of his climate newsletter. New Yorker: “If you anticipated that your life was going to be punctuated by one major disaster after another, would you be eager to have kids?”

Many of us struggle to balance our marrow-deep desire to have a child with the reality that they will grow up in a world that is constantly changing, with food and water shortages, social divide, and wars. There will also be frequent deaths from both conflict and natural disasters.

My husband, Sebastian, thinks that most people would rather be born than not, so even if things get fairly Mad Max, we’ll never face the day when our child looks us in the eye and says: “You knew all this was coming, and decided to bring me into this situation, when I didn’t need to be here?” Personally, I’m not so sure. One 16-year-old I spoke with explained that it isn’t that she wishes to be dead, but she finds her parents’ lack of thoughtfulness astonishing. “What were they doing? Were they not aware of the situation? Because I’m so stressed out about my future,” she said. Similar to climate-aware therapists Caroline HickmanShe wrote about a few of her clients who are angry at adults because of the climate crisis and cannot bear to be with their parents. I find this potential resentment the most disturbing of all the considerations that a prospective mother could make.

When I described this concern to Sebastian, it unlocked a deeper dilemma—to have or not have kids as a source of deeper meaning and purpose. He said, “Why do people have kids? Is it because of the child? No. You don’t know them. You’re having kids for selfish reasons, largely. Imagine if we don’t have kids and one of us dies. The other one will be completely and utterly lost. If we have a kid, there will be a sense of a family and meaning from knowing you exist for another person beyond yourself.”

Perhaps I could use my selfish desire to make the world safer for our child as a stronger motivation. There’s nothing quite like having skin in the game, after all. The faulty element of this thinking, though, is that the climate crisis already threatens to hurt my friends’ kids and the young people in my extended family, let alone all the other children in the world. My skin is already in large part.

I feel more strongly that I want to have children to feel the deepest levels of human love. I certainly need one if I want to count tiny toes in bed with Sebastian on lazy weekend mornings—one of the most heartwarming visions in my mind. I want to know what happens in a long-lasting relationship with the little person we create. What will it bring you? What are the highlights, challenges, and big surprises? Would we feel more joy? Feel so moved by the desire to provide a happy life for this little one that a new layer in our human potential would be unlocked. Feel deeper registers of satisfaction for what we’d done with our lives?

I’ve never cared much for the idea of legacy, but I can’t rule out the possibility that there could also be some unconscious forces motivating me to try to build my legacy biologically. Ironically, child-free people have often been stigmatized as “selfish” for deciding to enjoy life without kids. This label is being used more often for those who decide to reproduce in the climate crisis. I’ve found parallels with Hickman’s research among some (not all) Gen Z youth I’ve spoken with, who expressed a new generational attitude: they believe that bringing new children into this world is unfair to those kids, and therefore speaks to the selfishness of the parents. Another way to look at it is that it takes tremendous courage and hope in humanity’s futurity to birth new babies at this time.

Editor’s note:Britt Wray, the author, had a baby boy in 2021.

Excerpted From Generation DreadBritt Wray. Copyright © 2022 Britt Wray. Published by Knopf Canada Limited (a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited). Reproduced by agreement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Chatelaine delivered to your inbox

We have the best stories, recipes and shopping tips. Horoscopes and special offers. Every weekday morning.