[ad_1]

A woman seeks relief from a high temperature (104F) in Kolkata, India on April 26, 2022.Debajyoti Chakraborty/AP

This story was originally published in the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

For the pastNazeer Ahmed has lived in one of the hottest spots on Earth for the past few weeks. India has been hit hard by a heatwave. Pakistan, his home in Turbat, in Pakistan’s Balochistan region, has been suffering through weeks of temperatures that have repeatedly hit almost 50C (122F), unprecedented for this time of year. Residents have been forced to stay at their homes due to severe shortages of power and water.

Ahmed is worried that things will only get worse. It was here, in 2021, that the world’s highest temperature for May was recorded, a staggering 54C. He said that this year feels even hotter. “Last week was insanely hot in Turbat. It did not feel like April,” he said.

As the heatwave has worsened energy shortages across the globe, India and Pakistan, Turbat, a city of about 200,000 residents, now barely receives any electricity, with up to nine hours of load shedding every day, meaning that air conditioners and refrigerators cannot function. “We are living in hell,” said Ahmed.

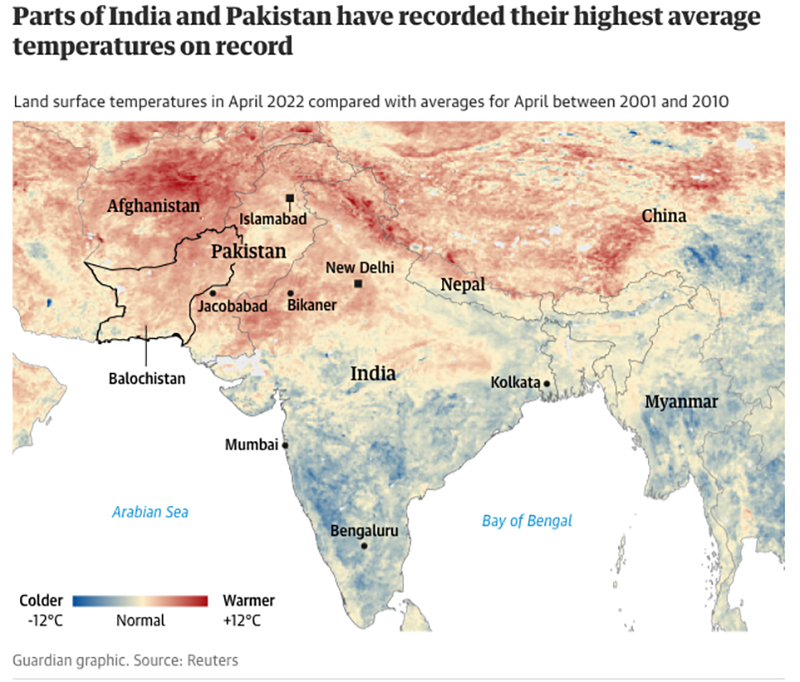

It has been a similar story in the subcontinent. More than 1.5 billion people are experiencing the effects of climate change. The scorching summer heat has arrived two months ahead of schedule and the relief promised by the monsoons is still months away. North-west and central India experienced the hottest April in 122 years, while Jacobabad, a city in Pakistan’s Sindh province, hit 49C on Saturday, one of the highest April temperatures ever recorded in the world.

The heatwave already has had a devastating effect on crops, including wheat. In India, the yield from wheat crops has dropped by up to 50 percent in some of the areas worst hit by the extreme temperatures, worsening fears of global shortages following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has already had a devastating impact on supplies.

In Balochistan’s Mastung district, known for its apple and peach orchards, the harvests have been decimated. Haji Ghulam Shahwani, a farmer, watched with anguish as his apples blossomed more quickly than a month earlier than expected. Then, despair as the blossoms smolder and then succumbed to the unseasonal heat, almost destroying his entire crop. Farmers in the area also spoke of a “drastic” impact on their wheat crops, while the area has also recently been subjected to 18-hour power cuts.

“This is the first time the weather has wreaked such havoc on our crops in this area,” Shahwani said. “We don’t know what to do and there is no government help. The amount of fruits that can be grown has dropped, and the cultivation has declined. This weather has cost farmers billions. We are suffering and we can’t afford it.”

Sherry Rehman, Pakistan’s minister for climate, told the Guardian that the country was facing an “existential crisis” as climate emergencies were being felt from the north to south of the country.

Rehman warned that the heatwave was causing glaciers in the north to melt at an alarming rate and that thousands of people were at risk of becoming caught in flood bursts. Rehman also stated that the scorching temperatures were not only affecting crops, but also water supply. “The water reservoirs dry up. Our big dams are at dead level right now, and sources of water are scarce,” she said.

Rehman stated that the global community should take note of the heatwave. “Climate and weather events are here to stay and will in fact only accelerate in their scale and intensity if global leaders don’t act now,” she said.

Experts say the scorching heat that is being felt across the subcontinent may be a sign of more to come as global heating accelerates. Abhiyant Tiwari, an assistant professor and program manager at the Gujarat Institute of Disaster Management, said “the extreme, frequent, and long-lasting spells of heatwaves are no more a future risk. It is already here and is unavoidable.”

The World Meteorological Organisation said in a statement that the temperatures in India and Pakistan were “consistent with what we expect in a changing climate. Heatwaves are more frequent and more intense and starting earlier than in the past.”

A heatwave occurs when the maximum temperature is greater than 40C or is at least 4.5C higher than normal.

#PakistanToday, temperatures reached a blistering 49C (120.2F).

This is one of the hottest April temperatures ever recorded. pic.twitter.com/AnIxNnjfwU

— US StormWatch (@US_Stormwatch) May 1, 2022

According to the India Meteorological Department, Bikaner was the country’s hottest place at 47.1C over the weekend. However, in some parts of north-west India, images captured by satellites showed that surface land temperatures had exceeded 60C—unprecedented for this time of year when usual surface temperatures are between 45 and 55C.

“The hottest temperatures recorded are south-east and south-west of Ahmedabad, with maximum land-surface temperatures of around 65C,” the European Space Agency said on its website.

The extreme heat has put enormous pressure on India and Pakistan’s power demand. Many have been forced to endure hours of power outages due to the intense heat. According to the government, India’s peak power demand reached an all-time high Friday of 207,111 megawatts.

India is experiencing its worst electricity shortage in six years. As domestic coal supplies have declined to critical levels, and as the price of imported coal has risen, power cuts in several states, including Jharkhand and Haryana, Haryana and Bihar, have been imposed for up to eight hours. Indian Railways cancelled 600 passenger and mail train journeys to expedite the transport of coal throughout the country.

[ad_2]