[ad_1]

Final sample

The final sample contains 51 articles that include 89 datasets sourced from 33 countries, with a total number of 119.465 participants. The final sample comprises Africa, Asia and Europe, India, North America, Oceania, and Europe. 64% of the sample comes from Europe (SupplementaryFig. 1).

Assessing publication biases and heterogeneity

We conducted trim and fill analyses to assess publication bias. One study was imputed for fairness and education. We made minor adjustments to the effect sizes (from r = 0.65 to 0.63 for fairness and from r = 0.132 to 0.130 for education). These analyses all indicated that publication bias is not problematic.

We analyzed dispersion using all determinants. Q statistics, PValues Q, I2?, t295% prediction intervals, (PI). Q I2 suggest substantial heterogeneity. It should be noted, however, that heterogeneity can be substantial. QThat increases with increasing sample size I2It is not an exact measure of heterogeneity16. We were encouraged to put our efforts into focusing on t295% PI. We also performed explorative subgroup analyses on categories to further examine the heterogeneity. k ≥ 2. These analyses covered (1) construct subtype (2) policy domain (3) sampling region. We settled on k ≥ 2 to increase power and decrease the risks of introducing confounds associated with k = 1. = 1. 2 3). We also compared studies comparing economic policies with regulations in policy domain (Supplementary Tab). 1). Economic or price-based policies aim to directly affect prices (for instance taxes), while regulations control production quantities or pollution.17By using, for instance, bans to regulate unwelcome behaviours. We compared studies that included participants from Asia, Europe and North America (see Supplementary Figure). 1Distribution of regions We performed subgroup analyses to compare trust in implementing institutions with trust in political and representational institutions for trust. Implementing institutions refers only to institutions that implement policies in a nonpartisan manner. This includes the legal system and the public administration. Political institutions, on the other hand, are based on different political interests such as parties or government.18(Supplementary table) 4).

Main analyses

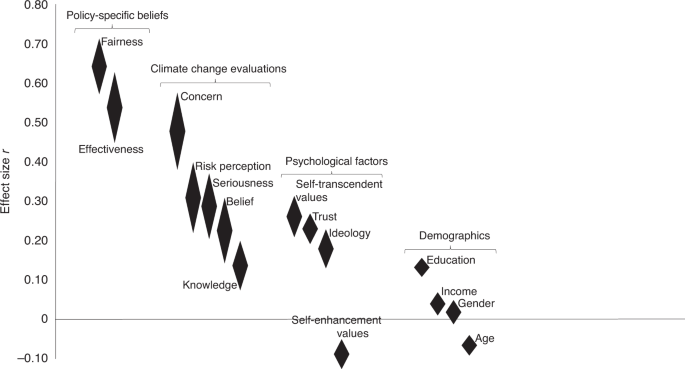

We ran separate random effect meta-analyses on each determinant using comprehensive Meta-analysis. The results were 15 meta-analyses (Table 1). Additional Table 5Fig. 2Provide a list of exclusion determinants and forest plots to all 15 determinants.

Beliefs that are policy-specific

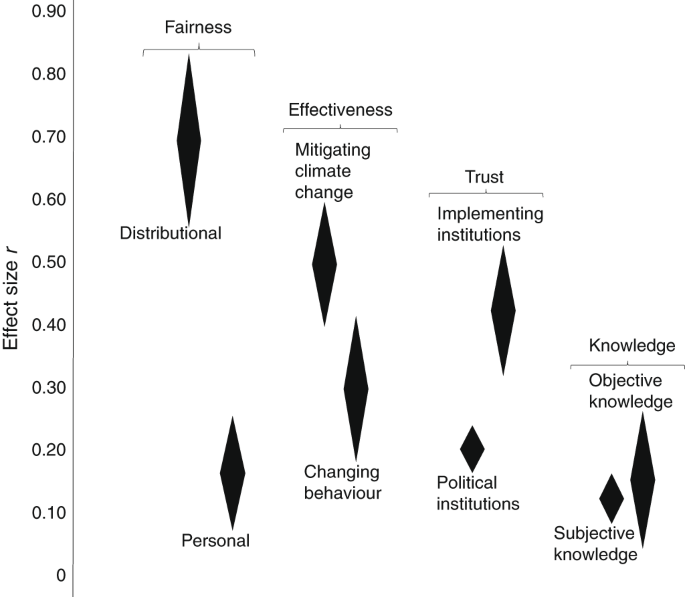

The strongest relationship between fairness and public opinion was found among all determinants (r = 0.65, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.57, 0.71); Fig. 1). Fairness refers to the degree to which people, processes, or distributions are treated equally or according to a set of criteria like need or merit.10,19. We found strong evidence for distributional fairness when we looked at subtypes.r = 0.73), measuring participants perceived fairness of policy distributions, for example how subsidies or taxes are distributed between or within specific groups. Personal fairness was less affected than the other variables ().r = 0.17, Q = 26.87, P < 0.001; Fig. 2), measuring how fair a policy is perceived “for me”. The sampling region did not affect fairness.Q = 3.27, P = 0.35) but a stronger relationship was found for regulations (r = 0.78) compared to economic policies (r = 0.57, Q = 18.26, P < 0.001)

Effectiveness refers to people’s beliefs that a policy can fulfil a specific aim8. We found that effectiveness was the second strongest determinant overall (as a whole).r = 0.54, 95% CI (0.45, 0.63)). Subgroup analyses revealed stronger relationships between taxes and laws aimed to mitigate climate change (r = 0.50) than those aimed at changing behaviour (r = 0.30, Q = 5.64, P = 0.018). According to the results of fairness (0.018), effectiveness was not significantly influenced by sampling area (0.018).Q = 2.31, P = 0.32) but, again, a stronger relationship was found for regulations (r = 0.73) compared to economic policies (r = 0.49, Q = 14.11, P < 0.001).

Perceived fairness was the most important determinant of public opinion about climate change laws and taxes. It showed stronger relationships to public opinion than when it was perceived to be personally fair. Public opinion was strongly correlated with policy effectiveness, particularly when the policy was perceived to be effective in mitigating climate changes. There was no evidence of support for regional variations. Comparing different policy types, both fairness as well as effectiveness showed stronger relationships to regulations than to economic policies when determining public opinions.

Climate change assessment

Five types were evaluated for climate change. Climate change concern can be defined as people’s degree of concern or worry about climate change20. Climate change risk perception measures the perceived personal or societal threats that climate change has on well-being.21. Climate change seriousness refers a person’s perception of climate change as a serious issue11. Climate change belief measures people’s belief in anthropogenic climate change22. Finally, climate change knowledge assesses people’s subjective or objective knowledge about climate change.

Public opinion strongly correlated with climate change concern (r = 0.48, 95% CI (0.37, 0.58)), while both climate change risk perception (r = 0.31, 95% CI (0.19, 0.41)) and climate change seriousness (r = 0.29, 95% CI (0.19 0.38)) showed medium-sized effects. There were no significant differences in concern between subgroups for each region.Q = 0.17, P = 0.92), seriousness (Q = 2.58, P = 0.11) or climate change risk perception (Q = 2.05, P = 0.36).

Recent data suggests that the overwhelming majority of Americans believe in climate changes, while only 10% claim to deny it.23. Importantly, in different cultures, denial has been reported24. This meta-analysis showed a weak to moderate relationship between climate change belief (and public opinion) (r = 0.23, 95% CI (0.14, 0.31)). This relationship was strong in North Americar = 0.61), of medium size in Oceania (r = 0.36) and weak in Europe (r = 0.17, Q = 11.82, P = 0.003).

It is difficult to make informed decisions about climate change mitigation if one does not have sufficient or incorrect information.25. Although knowledge can be considered a necessary, but not sufficient precondition to climate change awareness and concern, past research shows that it is positively related to this.20,26. One important limitation to measuring knowledge is the inconsistency between what people believe is true, and the actual evidence for the issue.26. Past research has shown that objective knowledge is positively related with environmental issues such as climate change belief or environmental risk perceptions. However, there have been smaller or even more negative relationships reported for subjective knowledge.21,22. Our meta-analysis showed that knowledge was not positively associated with public opinion (r = 0.14, 95% CI (0.07, 0.20)). We also found no significant differences between objective knowledge (r = 0.16) and subjective knowledge (r = 0.13, Q = 0.23, P = 0.63).

In summary, knowledge about climate changes was only weakly positively related with public opinion. Climate change belief was weak to moderately related to public opinion. Medium-sized relationships were found with climate change seriousness and risk perception. Climate change concern was the strongest determinant of climate change evaluations, with a strong positive relationship to public opinion. On the basis of effect sizes and 95% CI, these results indicate that ‘problem-based’ evaluations (climate change concern and climate change risk perception) are more strongly related to public opinion than ‘knowledge-based’ evaluations (knowledge and climate change belief).

Psychological factors

Values are defined as desirable goals serving as guiding principles in people’s lives27,28. Studies in the past have distinguished between selftranscendent values from self-enhancement. Self-transcendent or universalism values are those that prioritize universalalism or altruistic/biospheric values. These include a world at peace and social justice, unity in nature, respecting the earth, and a world at peace. Self-enhancement or egoistic, deceptive values measures the importance of authority, social power and wealth. Acceptance of environmental policies such as energy policy and congestion charge has been linked to these values.12,29,30. Our meta-analyses showed that public opinion was positively correlated with self-transcendent value (r = 0.26, 95% CI (0.21, 0.31)) and negatively related to self-enhancement values (r = −0.09, 95% CI (−0.12, −0.05)). Analysis of subgroups across different regions showed weaker relationships for selftranscendent values within the Asian sampler = 0.07) compared to both Europe (r = 0.28) and Oceania (r = 0.30, Q = 12.60, P = 0.002). Self-enhancement value self-enhancement was not significantly affected by subgroups (0.02).Q = 0.02, P = 0.89).

Trust can be defined as a “psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based on positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” (page 395, ref. 31). Past research has shown that distrust can be negatively associated with accepting both fuel taxes or road pricing.32,33. Our meta-analysis results showed a positive relationship for trustr = 0.23, 95% CI (0.19, 0.27)). Subgroup analyses revealed stronger trust in implementing organizations (r = 0.43) than trust in political institutions (r = 0.21, Q = 13.56, P < 0.001). Samples from Asia also showed stronger effects (r = 0.54) and Oceania (r = 0.55) compared to Europe (r = 0.19, Q = 29.03, P < 0.001).

Meta-analytical results showed that being politically right or conservative (versus left and liberal) was negatively related to public opinion (r = −0.18, 95% CI (−0.24, −0.13)). Although the overall effect was modest to moderate, we found a stronger relationship between North America and Europe (-0.24, -0.13).r = −0.34) than in both Europe (r = −0.15) and Oceania (r = −0.09, Q = 23.52, P < 0.001).

Public opinion was positively influenced by self-transcendent values, trusting in institutions, and identifying as a political left or liberal. Overall, these effects were small-to-medium-sized. However, ideology was strongly correlated with public opinion in North America. A smaller effect for trust was observed in the European sample. The Asian sample had non-significant effects on self-transcendent value. Surprisingly, the relationship between self-enhancement and self-enhancement was weak ().r = −0.09), indicating that holding egocentric values is not a strong barrier for accepting policies aimed at mitigating climate change.

Demographics

Public opinion was positively associated with education (r = 0.13, 95% CI (0.11, 0.15)). Policy domain was not affected by significant subgroup differences (Q = 0.04, P = 0.84), however, the association between education and public opinion was not significant in Oceania (r = 0.04, P = 0.09).

Both income and age had small but significant effects. This suggests that younger people are more likely to be successful.r = –0.07, 95% CI (–0.09, –0.04)) and having higher income (r = 0.04, 95% CI (0.01, 0.07)) were both related to public opinion. The statistical significance of age on economic policies was statistically significantr = −0.08) but not for regulations (r = −0.02, Q = 4.42, P = 0.04), while no significant differences across regions were detected (Q = 4.56, P = 0.18).

Gender had no significant overall effectr = 0.02, 95% CI (−0.01, 0.05)). No significant effects from either regionQ = 1.68, P = 0.64) or policy domain (Q = 0.80, P = 0.37) were found.

Public opinion was negatively correlated with being younger, having a higher income, and having higher education. Gender had a negligible effect on public opinion.