From 1600 CE, there are many instances where Bishnoi men or women have died to protect other living beings.

Shyam L. Bishnoi, a 28 year-old man, was raised in Khejarli in Rajasthan’s desert region. He followed his father’s footsteps in ecological conservation and has committed his life to his father and mentor’s teachings. Ghewaram was also a villager who established a rescue centre for stray animals. He has vowed to protect the wildlife there.

Shyam Lal hosts weekly gatherings to teach children that appreciation of nature is the first step in caring for it. He teaches children how to properly dispose waste and how to reduce, reuse, recycle and reduce. To support their local animal shelter and report any cruelty to animals or trees.

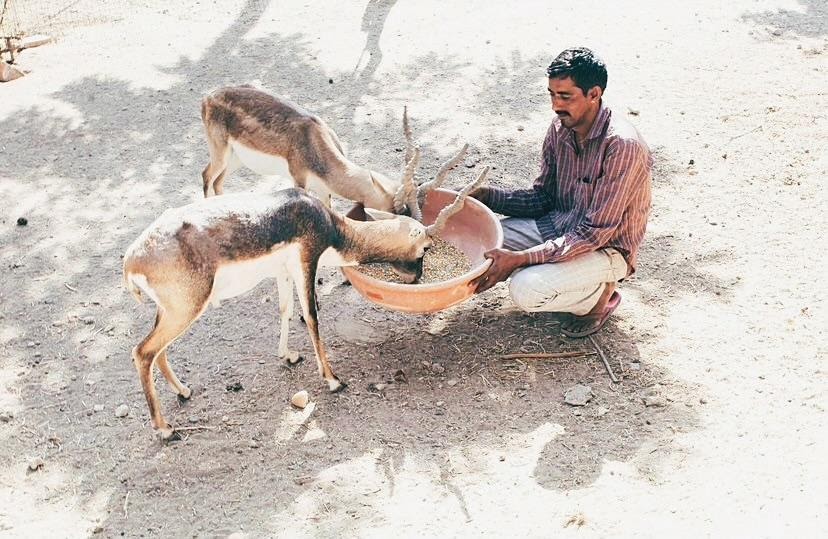

“A Bishnoi gives his life to protect wildlife from poachers, and our women look after orphan fawns and even feed it milk along with their own child,” he tells The Citizen.

Shyam Lal and Ghewaram discuss September 1730’s Khejarli massacre, in which 363 Bishnois died while protecting a Khejri grove. This campaign had a lasting impact on political ecology and is often referred to as the precursor of the Chipko movement in the 1970s.

They recount. The Maharaja had sent his men to Khejarli to cut down trees so that he could build a new palace. Amrita Devi, a brave Bishnoi woman, discovered the impending order and raced to Khejarli where Khejri trees were abundant. She confronted the royal troops.

Amrita Devi was escorted by her relatives and neighbors to stop soldiers from cutting down large quantities of trees. After all other options had failed, Amrita Devi hugged a tree that was being felled to save it.

The troops decapitated the woman, whose last words, sar saanthe runkh reho to bhi sasto jaan, if a tree is spared at the expense of one’s life it is worth it, are now legacy.

Amrita Devi was an environmentalist and a hero from Khejarli village, Rajasthan. She died with her three daughters Asu, Ratni, and Bhagu at the altar of Bishnoi Dharma, they tell.

Amrita Devi’s long and distinguished history in the Bishnoi community is a testament to her greatness. To commemorate her eternal sacrifice, a Khejarli fair is held each year on the anniversary her martyrdom.

Each year, the governments of Madhya Pradesh (and Rajasthan) present the prestigious Amrita Devi Smriti Award at the state level to recognize outstanding contributions to wildlife conservation and protection.

Shyam Lal and Ghewaram state that there have been documented cases where Bishnoi men or women died to protect other living things. The Bishnoi are committed to the preservation and protection of the environment and natural life.

They claim Guru Jambeshwar, a Rajput leader hailing from Marwar in western Rajasthan, established the Bishnoi family. He gave 29 commands that must be kept by a Bishnoi until their death. The most important of these are about protecting and respecting all living things. The Bishnoi are required by God to provide safe shelter for abandoned animals. They are forbidden from cutting trees and must promote resource-sharing with the fauna.

Now, they claim that their way is a mixture of their roots and current practices. Despite threats to safety, Bishnoi activists carry on their work in the desert despite all.

During my visit I found the community indicate that the Bishnois wrath against “poaching” extends beyond the corridors of a religious vision. They have a warm relationship built with non-human animals. They share their fields and sacred areas as well as their homes with them. Sometimes they care for injured or weak birds.

The khejri is an important food source

“Every living creature has the right to exist peacefully,” says Shyam Lal Bishnoi. “Other communities must absorb and practise the teachings in environmental commitment, so the earth will truly be inhabited by environmentally conscious people.”

He stated that although the species is listed as endangered under the First Schedule to the Wildlife Protection Act it has seen an increase in poaching.

The global vulnerable gazelle, the chinkara (previously widely distributed in India), is being threatened by mechanised agriculture and rising human populations.

Shyam Lal describes how some poachers believe that it is acceptable to kill animals for pleasure and that their lives have no meaning. He also mentions that habitat loss due to urbanisation and industrial expansion are other risks.

Discouraged by the hunters’ attacks, Bishnoi activists in western Rajasthan have created a strong communication network and stage anti-poaching protests regularly to question the link between law, justice and democracy.

Kapil Chandrawal describes the Jaisalmer forest’s deputy conservator. He also describes the chinkaras as well as other animals that are subject to wildlife conservation, rescue, and treatment centres run local residents.

“The villagers’ effort to rescue and safeguard its species is remarkable, and they play a big hand in its protection. This practice has been in place for centuries. The locals fear this sect,” says Chandrawal.

A few of the village’s rescue centers are run by local residents, where injured deer, Nilgai infants, rabbits, peacocks and other species are brought in. After being treated, they are returned to their village grasslands.

Ghewaram Lal and Shyam Lal describe global warming as the greatest threat to modern humans and the natural realm. They explain how they constructed ponds to house these animals. However, with global warming causing an increase in the surface temperature, water scarcity can sometimes occur due to evaporation.

They express concern at the fact that humans have wiped out 68% of global wildlife populations in just 40–50 years, and that 90% of us breathe harmful air.

“Only we are the key to a better life and a healthy planet, it all begins with us, and only we together can transform our future,” they tell The Citizen, emphasising that human activities are the primary cause of global warming.

Despite the hardships they endured during the pandemic they say that Ghewaram, Shyam Lal and their cattle have continued to run the Khejarli rescue centre despite the difficulties.

“The future is in our hands, we need to act decisively because nature is our biggest and most valuable ally.” The message this pioneering ecologist community has for the country’s other citizens.

Photographs: Swapnil Mittal