Friedel Klussmann existed before San Francisco had a comprehensive tree-planting program. Dorothy Erskine was the first person to protect rolling hills from being overcrowded before City laws were passed. Before there was a movement protecting San Francisco Bay from being filled in with development, Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr and Esther Gulick were there.

San Francisco is long considered an environmental leader on the global stage. But behind this image lies a long history full of women who have fought for freeways, protected open spaces and saved the Bay.

“There was this network of civically-minded ladies that provided the leadership that helped save the region,” said Amanda Brown-Stevens, executive director of Greenbelt Alliance, a Bay Area-based environmental nonprofit.

Given the times, she said, “these women weren’t going to go into leadership positions or even have jobs. And at the same time, they still had that civic energy….and didn’t necessarily have a lot of outlets for that.”

In celebration of International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month, The Examiner is highlighting a few of those women who, despite many odds, made The City’s eco-identity possible.

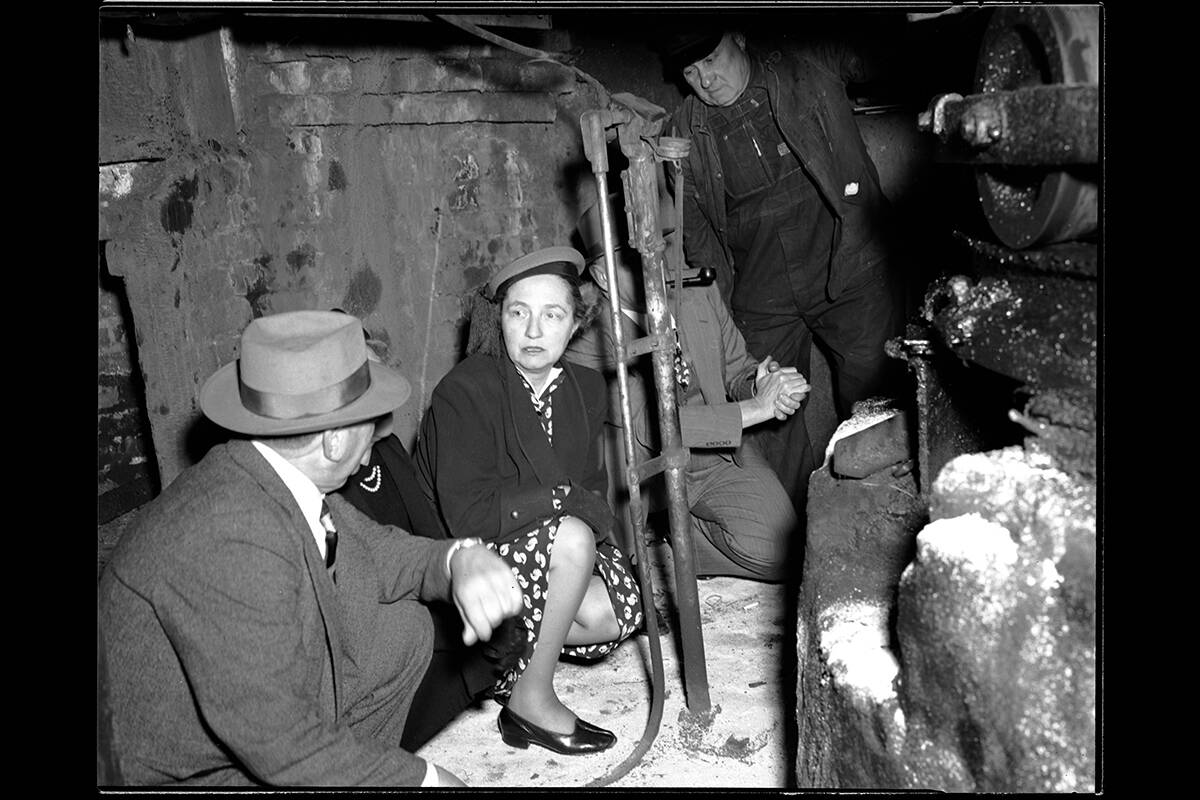

Friedel Klussmann, Mr. A. O. Olson and the Powell and Market Street Cable Car turntables in May 1949. (Courtesy SFMTA Photo Archive).

Friedel Klussmann says it started with cable car. Or, rather it began with the threat of losing them.

Many saw the future of asphalt and gas-powered automobiles after World War II. “Cable cars were already antiques at that time,” said Darcy Brown, executive director of San Francisco Beautiful, a nonprofit Klussman founded in 1947.

But Lapham’s plan to “junk the cable cars” was complicated by Klussmann, who formed a coalition to oppose the measure and began a public campaign to demonstrate that the value of San Francisco’s cable cars was greater than their operational cost.

“Friedel Klussman was just your average neighborhood lady,” said Brown. But, “she decided this was not a good idea. She was far more forward-thinking than the mayor.”

Ultimately, Klussamn’s actions forced a referendum on an amendment to the city charter, compelling the city to continue operating the lines. “Diesel buses did not prompt romance in the minds of riders, and there were no thrills to be found in chugging over a hill, belching exhaust fumes as it went,” the Cable Car museum wrote in commemoration of Klussman’s victory.

Her civic activism didn’t stop there. In the 1960s, her organization partnered with the Chamber of Commerce to jumpstart San Francisco’s first tree planting program and merged with the Chamber’s litter program to clean City streets and promote green space throughout the city.

Preservation of open space was also important to Dorothy Erskine, a lifelong resident of San Francisco who watched as the sand dunes and lupin bushes surrounding her home on Broadway and Divisadero gave way to housing as the City’s population boomed following the first World War.

“You saw the city begin to fill up with people,” she said during an oral interview with the San Francisco Public Library. “And after a certain point, the filling up process was anything but welcome. You wanted the open spaces. You wanted something left.”

In the late 1930s, Erskine and a cohort of women who attended the University of California Berkeley became engaged in urban planning and conserving the City’s dwindling open spaces.

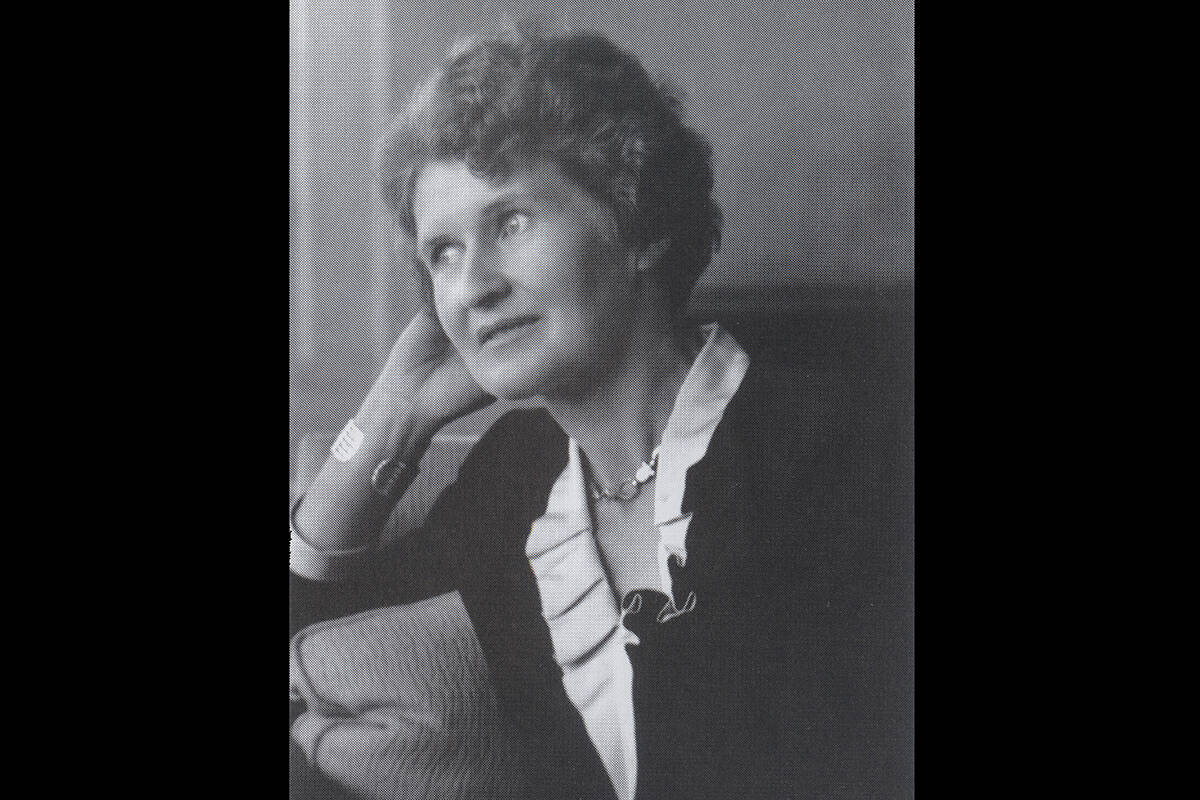

Dorothy Erskine in an undated photograph. (Courtesy Greenbelt Alliance)

Erskine was aware that the City did not have a planning department. He wanted one because urban planning was vital to solving many of the most pressing social problems.

“There was a real push at the time that modernizing meant developing everywhere,” said Brown-Stevens. “And I think women like Dorothy said hey, what part of what makes the Bay Area special is the natural landscape that surrounds us.”

Erskine is also the founder of SPUR and The Greenbelt Alliance. Proposition J was a charter amendment that allowed for funds to be set aside by the City to purchase the last remaining hilltops. This allowed the City’s preservation of open spaces.

“It really was this moment of “‘we need to step up as citizens,’” said Brown-Stevens. “It was this idea that local people can stand up and make a difference by putting together and advocating for a different pattern of development. And that, I think, has been a huge legacy and is what is special about the Bay Area.”

But it wasn’t just San Francisco’s land that was filling up with people and development. It was also happening in the Bay.

By the late 1950s, nearly a third of San Francisco Bay’s tidelands had already been diked off and filled, and plans to expand such landfills throughout the region were on the rise. Berkeley, for instance, proposed a plan to pave nearly 2000 acres of Bay.

But an Oakland Tribune article outlining the plans galvanized Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr, and Esther Gulick – all wives of prominent UC Berkeley faculty members – into action. “It showed that the Bay could end up being nothing but a deepwater ship channel by the year 2020 because of the enormous amount of fill being planned,” Gulick said in a speech at UC Berkeley in 1988.

The trio quickly realized that there was little interest in three women saving the Bay. “It was totally a man’s world,” said David Lewis, executive director of Save The Bay, an environmental nonprofit. “There were almost no women elected officials. The leaders of the conservation organizations, which were national organizations focused on protecting wilderness, those leaders were all men.”

Lewis said that this was before the spirit of environmentalalism permeated the Bay Area. “There were basically no environmental laws or regulations to prevent (fill) from happening, and there wasn’t even that much public awareness that it was happening,” he said.

McLaughlin and Kerr started hosting events in their homes to spread awareness. Erskine also attended. “They built a movement with phone calls and handwritten letters,” said Lewis.

The movement gained momentum eventually. Along with public support, membership in Save San Francisco Bay Association (now Save The Bay) soared. To study the effects of such fill, a study was ordered. The study could not be completed without a moratorium on filling the Bay.

This momentum eventually led in 1965 to the passage the McAteer – Petris Act, which created the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), which designated the Bay as an State-protected resource and charged BCDC with protecting it from indiscriminate filling.

Today, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC) is a permanent agency that preserves and protects the Bay. After decades of stewardship, the size of the Bay has increased significantly and hosts the nation’s largest urban wildlife refuge and thousands of acres of permanently protected wetlands, salt ponds, and managed marsh.

“These women were heroes, not only for what they did, but the environment in which they did it, which was not particularly welcoming to women,” said Lewis. “Women were the last people that anybody in the halls of power was expecting to listen to.”

Though it can be easy to take San Francisco’s tree-lined streets, scrubby hilltops and sprawling blue Bay for granted, let today be a reminder that you can thank a woman for that.

On February 24, 1979, Dorothy Erskine park was dedicated. From left: Dorothy Erskine, Ken Hoegger and Tom Malloy. (Photo by Greg Gaar, courtesy Ken Hoegger & the Sunnyside History Project.