[ad_1]

Alok Sharma, COP26’s president, said that the conference was a result of almost 200 countries. Adopting the Glasgow PactThe world had kept 1.5 degrees within reach, but NotedIts “pulse” is weak.

Scientists warn that if the temperature rises above this level, there is a high chance that many will suffer. The Arctic ice sheet could be disappearing and island nations could find themselves underwater. Developing countries are already being impacted by climate changeExtreme weather events are more likely to occur in areas that are more vulnerable. Bushfires will burn more intensely, the oceans will become acidic, and hurricanes are more likely to wreak havoc on cities.

Subscribe to the CNET Science newsletter

CNET Science newsletter reveals the most amazing mysteries of the Earth and the universe. Delivered Mondays

Since 2015, when the Paris Agreement was adopted, the world has been trying to keep global temperatures from rising above 1.5 degrees Celsius. However, this effort began earlier this year. The IPCC’s latest report on the physical science base of climate changeThese aspirations were severely hampered by the onset of the Great Recession. Climate scientists believe that we are very likely to exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius of temperature on our current trajectory. There is only a small window of opportunity to achieve this target.

This is supported by projections. The International Energy Agency (IAEA) announced that if countries meet their pledges “in whole and on-time”, we might limit the rise in global temperature to 1.8 degrees Celsius (3.2 degrees Fahrenheit). A week later, Climate Action Tracker suggested that meeting those same pledges put the planet on course for a rise of 2.4 degrees Celsius (4.3 degrees Fahrenheit).

Although temperature increases have been a focus of climate discussions for a long time, they don’t reveal enough about the impacts humans are having on the Earth. The planet doesn’t heat up evenly. The climate system governs and is governed by a complex series of interactions among seas and skies and forests and deserts, as well as oceans and icecaps.

Humans are creating unpredicted changes in the world by burning fossil fuels and releasing greenhouse gases. Already, the Earth has warmed 1.1 degrees Celsius. Some of those changes are happening today.

How much will temperatures rise before the end of the century This is a wrong question in some ways. Instead, we should explore and center the wide-ranging, often overwhelming, impacts these increases will have on the planet.

On Aug. 15, 2021, forest fires erupted throughout northern Morocco.

Fadel Senna/AFP/Getty images

Global mean temperature

Two critical temperature benchmarks are constants when it comes down to limiting global warming.

These numbers refer to an increase in the “global average temperature”, which is the average temperature on Earth. Since generations, scientists have known greenhouse gases, and in particular carbon dioxide, play a crucial role in warming the planet. This fact was discovered by Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish scientist.

Our understanding of this relationship has only grown since Arrhenius. For example, Scientists can drill through thick ice to retrieve rod-like coresThese are planetary timestamps. Cores taken from Antarctica show that global mean temperatures are well aligned with carbon dioxide levels. They can be traced back as far as 800,000.

Global mean temperatures are not a reliable instrument. Not necessarily a bad tool. There is value in projecting how much planet’s average temperature will rise based upon how much carbon dioxide we release into the atmosphere.

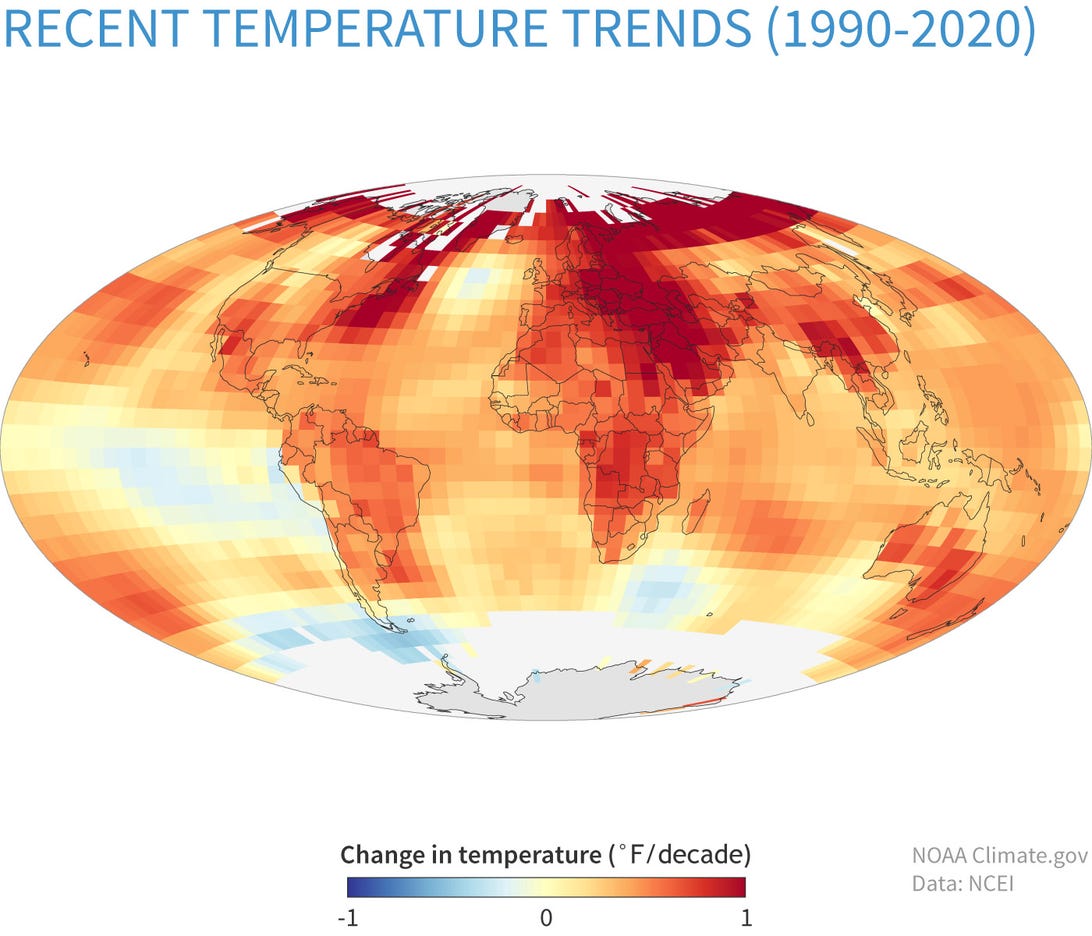

Trends in global mean temperature between 1990 and 2020 in degrees Fahrenheit per decade.

Climate Action Tracker and the IEA examine the amount of carbon dioxide that is expected to enter our atmosphere based upon pledges to reduce emissions. They then use relatively simple calculations in order to calculate how much temperature rises if pledges are fulfilled.

These calculations don’t necessarily mean much. For example, if I raise the thermostat by 1.5 degrees Celsius in my apartment, it would be hard for me to notice the difference. The planet is too binary to be considered a whole story.

Andy Pitman, director of ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (Australia), says that “these global numbers don’t actually map onto risc.” “There is no nuance to the conversations.”

Global mean temperatures benchmarks are useful because they set targets that can be met. Understanding how different levels might increase or decrease the Arctic ice coverage, or reorganize ocean ecosystems worldwide is what really matters.

This requires extremely complex climate models to be able to accomplish this.

Physics laws

Pitman states that climate models work because they obey the laws and laws of the universe.

Pitman said, “If you believe that astronomy works and your microwave works, an ultrasonic works,” Pitman added, “if those things work, it is because of the laws physics.”

“It’s these laws of physics that are built into our climate models to make predictions.”

Climate models have been around since the 1960s, and despite what you might read on the internet to the contrary, they have been around for a long time. Some of the changes in the climate are quite easy to predict.As a result of rising greenhouse gas emissions. “Even those primitive model in the ’60s had basic projections that have played out in real time,” Matt England, an Oceanographer at the University of New South Wales Climate Change Research Centre.

In the last 60 years, the complexity and resolution of the models has increased by magnitudes. There are dozens of models that provide different projections for different climate phenomena.

Some climate variables correlate well with rising global mean temperatures. For instance, certain temperatures will lead to melting ice sheets and rising sea levels. In practice, scientists are unable to plug 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming into a digital Earth to see the entire world that the computer generates. To simulate such a world, you’d need an incomprehensible amount of computing power. Pitman emphasizes that these climate models are independent of models used by Climate Action Tracker or the IEA to project how much the world would warm on average.

Climate scientists use dozens upon dozens of models to help them predict climate changes that might occur at higher temperatures. They aren’t perfect and can be subject to uncertainty. “There’s always going be some uncertainty because different models simulate climate in slightly different ways,” Sarah Perkins Kirkpatrick, a UNSW Canberra climate scientist, says.

Perkins-Kirkpatrick is an example of a heat wave researcher. She studies how warming at 1.5 and 2 degrees Celsius, and more, might affect the frequency or intensity of these events. The models show that lower temperatures are worse, but the uncertainty grows as temperatures rise.

It’s not that things get better. But, we still don’t know how much worse.

Although it is difficult to predict how warming of 2 or 3.degree Celsius could affect smaller scales, science is still in its infancy. It’s difficult to predict how weather patterns, ocean currents, land and other factors will change and what feedback loops will result. Pitman claims that there is no correlation between the global average temperature rise, and the fingerprint of extreme weather events that impact a city or region.

This is where the blunt instrument global mean temperature increase fails to convey the urgency and dire situation we are in.

Too much warming

The science behind 1.5 degrees Celsius warming is well understood. Climate scientists have carefully examined the impacts of this warming on different ecosystems, regions and weather patterns. This is what forms the basis for A special report by the IPCC published in 2018.

The outlook in that report is dire. It has been three years since its publication. Even in the face of a global pandemic it has been a constant battle to continue burning fossil fuels and to add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere at alarming rates.

England states, “I think it is pretty much agreed across scientific community that avoiding 1.5 degree Celsius is practically impossible now.”

China, India, the US and the EU are the major emitters. They have all committed to reducing their emissions more strongly in the run-up to and during COP26. Climate policy scientists made their suggestions in Science, Nov. 5, writing in the journal Science The new pledges indicated a “strengthening ambition through 2030”With a “stronger near term foundation to deliver on long-term goals of Paris Agreement.”

This analysis depends on the latest pledges being kept on time and in full. It’s not a given. England says that the uncertainty about the future of the planet rests on where humanity will emit its greenhouse gases.

In September 2021, a glacier in Norway collapses into the ocean north Svalbard.

Olivier Morin/Getty

In the first week at COP26, the notion that we might limit global warming to 1.8 degrees Celsius was deemed “optimistic”. A week later 2.4 degrees of warming were described as “catastrophic.”

Unfortunately, limiting the average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees is too much warming. We shouldn’t stop trying to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. However, we must be realistic. This is not a reason to give in. This gives you even more motivation to decarbonize rapidly — the alternative would be far worse. Perkins-Kirkpatrick states that “2 degrees” will not be possible “Very soon.”

These numbers indicate more than summers becoming slightly warmer in San Francisco or Sydney. The planet’s reaction will be different across its oceans, ice, and land. These numbers could indicate irreversible changes in Earth’s climate. This is what climate models tell us.

How much warming can we anticipate by the end of this century? How much will temperatures rise?

It doesn’t matter what number it is, it’s still too much.