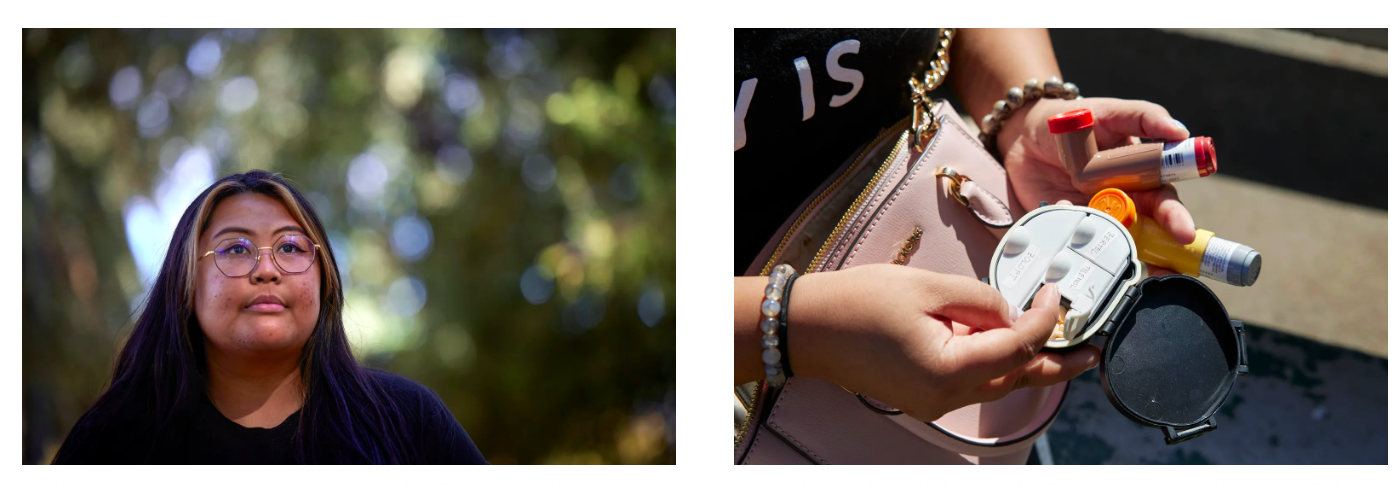

It was a clear day, the kind that makes South Stockton’s consistently filthy air difficult to imagine. But in one of California’s most dangerously polluted communitiesThe state has the highest number of asthma attacks-related emergency room visits.

“No matter what, air quality is always an issue in my life,” Pana said, “something I have to be constantly aware about.”

Assembly Bill 617 was passed in 2017.The law requires that local air districts and the state Air Resources Board reduce air pollution in marginalized areas. The law established the Community Air Protection ProgramThis is a group that consists of residents and local officials. It focuses on shaping regulations and steering the state money to a few hot spots.

Hailed as “Unprecedented” by some environmental groups, the law was supposed to create a program to measure and combat air pollution at the neighborhood level.

More than $1 billion has been spent so far on state funds for community grants, incentives to the industry, and other government costs. It’s not yet possible to determine if the program will improve the toxic and smog-filled air that nearly 4 million people breathe in. 15 communities.

Most of them Communities — including Richmond, West Oakland, Stockton, San Bernardino and Wilmington — have high poverty rates and are predominantly Latino, Black and Asian American.

Now, even as the law’s clean-air program prepares to fold in new neighborhoods, a major question lingers: Is it working?

“The jury’s out,” said Jonathan LondonUC Davis associate professor of human ecology who keeps an eye on the law. It’s “an ongoing experiment with the potential for significant benefits, but also significant obstacles.”

However, environmental justice advocates call it law toothless, Warn us it has “largely failed to produce the promised quantifiable, permanent, and enforceable emissions reductions.”

The struggle to achieve the law’s ambitious goals has been marked by battles between residents and local air regulators, and by jurisdictional juggling among agencies, each responsible for a different portion of pollution. People continue to be exposed to polluted air.

“Is it having the improvements that I want it to have, at the level that I wanted to have? No, we need a lot more,” said Assemblymember Cristina GarciaBell Gardens Democrat, authored the bill. “Is it engaging the community and empowering them, so they could push for change? Oh, definitely.”

The law is just one tool — and, its author acknowledges, an imperfect one at that — intending to fix decades of environmental racism, questionable land-use decisions and Construction of freeways that have left Communities of color in poor areas hemmed in by California’s industrial corridors. It’s a monumental task, and experts say no one law will be a panacea.

The health of your family is at stake Millions of people who live near California’s refineries, ports and freeways that are the sources of smog and other toxic pollutants that trigger asthma attacks and have been linked to cancer.

Staff from the California Air Resources Board recently It was called it “a catalyst to change the way we work with communities.”

Stockton residents, as well as community groups, have had a very different experience. They dealt with local air regulators about funding decisions or delayed air-pollution monitoring.

“At the beginning of this process, we were all kumbaya,” said Dillon Delvo, executive director of Little Manila Rising, a historic preservation organization turned environmental justice group in South Stockton.

“By the end,” he said, “it was terrible.”

‘Tremendous amount frustration’

For more than half a century, California’s State and local air regulators have enacted pioneering rules to clean up pollution from smokestacksAnd tailpipes. Trailblazing mandates to tackle diesel exhaust — a known carcinogen — and other toxic air contaminants cut Californians’ risk of getting cancer from bad air by 76%.

But it hasn’t been enough. Parts of California still have the worst air quality in the country, with about 87% of Californians living in areas that exceeded federal healthy air standards in 2020.

In the San Joaquin Valley alone, breathing fine particles is estimated to cause 1,200 premature deaths from respiratory and heart disease per year. Poor communities of color are still exposed to double the cancer-causing diesel exhaust than that of their more affluent neighbors.

Garcia’s law aimed to tackle pollution hot spots by creating a greater role for community activists and residents in the complex regulatory process. Local air districts responsible for regulating smokestack pollution must now work with communities to craft clean-air plans. The law also calls for increased air monitoring, bigger fines for polluters and faster deployment of new pollution-scrubbing retrofits on smokestacks.

Deldi Reyes, director of the Air Resources Board’s Office of Community Air Protection, told board members at an October meeting that there has been progress since the environmental justice law was enacted, with an estimated 75 tons of fine particles expected to be cut across 11 communities — equivalent to removing 75,000 heavy-duty diesel trucks from California roads.

But neither the law nor the state-developed guidelines for its implementation include specific targets for measurably improving air quality or public health in the selected communities. Though the program relies heavily on time and effort from community members, decision-making is ultimately left to state and Local air regulators.

“I’d like to see more accountability built into the program,” said Dr. John Balmes, a professor of medicine at UCSF and a member of the California Air Resources Board. “I don’t think that’s too much to ask.”

Reyes, however, urged patience. Of the 15 communities, three are still developing their clean-air plans and four are in their first year of implementation, she said. “It’s just too early to point to any of the communities and say, ‘Oh, they haven’t met their goals.’ Air quality does not change on a dime.”

An environmental justice advocate in Oakland, Margaret Gordon, agreed. “This is not instant. This is not Top Ramen.”

Even The law’s birth was contentious.

The legislation was written as a companion piece to a bill Extension of the life expectancy of cap and trade, California’s trailblazing carbon market designed to reduce climate-warming emissions. Cap and trade allows companies to trade or buy credits in order to reduce local pollution and meet a declining greenhouse gas emission limit.