[ad_1]

Are there ever going to be any point when car owners are able to say enough is enough and choose a different type of transport as global petrol prices rise and governments step in? If history is any guide, it’s unlikely.

New Zealanders suffered a severe shock over the past few weeks as fuel prices rose to more than NZ$3 per gallon, before falling to $2.60, after the government temporarily suspended the price. Fuel taxes reduced by 25cA litre was enough to ease the market. The government of Australia has promised to implement some type of Cost cutting measuresIn the upcoming budget.

These temporary actions are not permanent. greater price volatilityIt was predicted. And there is no doubt fuel prices are on the community’s radar. But will rising fuel costs affect behaviour? Unfortunately, the available data doesn’t tell us much.

Pain at the pump doesn’t change behaviour

Fuel prices change on either a weekly or daily basis. They are reported over the same time period, while robust fuel consumption statistics only are available for longer periods.

It is difficult to study consumer reactions to sudden price increases unless the price rise is a long-term trend and not a short-term spike. It’s not yet clear which of these two scenarios is confronting motorists today.

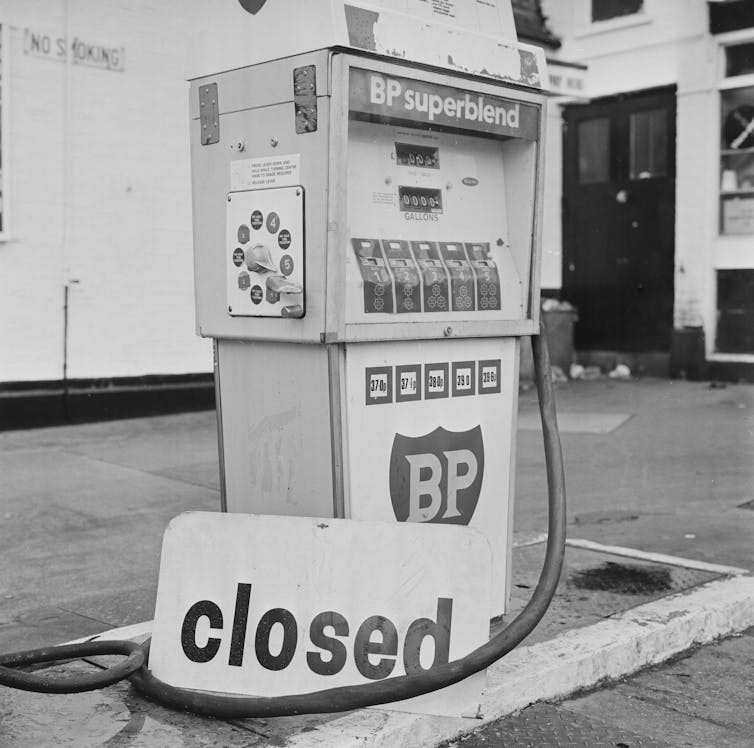

Evening Standard/Getty Images

To study the consumer reaction to a rise in fuel prices over time, one must go back to the 1973 oil crisisWhen oil prices abruptly quadrupled, and stayed that way more than a full year.

What can motorists do when faced with a sustained and massive increase in petrol prices. As seen during the 1973 crisis and beyond, the consistent answer to this question is “not much”.

Read more:

Why Russian gas could upset Germany’s bolder climate plan

The number of cars in New Zealand has increased over the years following the oil crisis. It is now ranked fourth on the OECD. Ownership of a car.

While some reduction occurs over the longer term, petrol consumption appears to be “inelastic” to price changes. In economic parlance, A inelastic goodThis is one in which the price of the product does not affect its demand.

Lynn Grieveson/Getty Images

A complex market driven petrol

Despite this, there are many complexities within the market and the general trends in fuel usage may not be obvious.

Petrol consumers include millionaire Porsche owners who are able to drive off to their holiday home, and contract cleaners who are able to drive to their next job in a rusty Nissan Micra.

A Study by the US in 2019 divided this range of households into two groups to study their behaviour separately: “hand to mouth” and “non-hand to mouth” consumers.

Hand-to-mouth households don’t reduce their fuel consumption because it is simply not possible. Their petrol consumption has been reduced to non-discretionary use, which is often related to work. This expenditure cannot be reduced without reducing income.

Often the “gig” work that such households rely on is inflexible and not public transport friendly. In these circumstances, it is difficult to buy an electric vehicle (EV).

Non-hand-to mouth households don’t reduce their fuel expenditure because it supports activities or benefits that are often of far greater value than the extra cost imposed by rising fuel prices.

It is not an ideal solution to have cheap public transport.

For example, I commute 15km each day to work. This might use about three litres of fuel (I’m not really sure, which is a comment in itself). My fuel cost will go up from $6 to $9 per day if it goes up from $2 to $3. This trip was made by public transport. Reduced from $6 to 3.

I could use public transport, which would save me $6 per day. A round trip by car takes 40 minutes while a trip on public transport takes more than three hours. What is the value of two hours and twenty minutes per day?

Even at the minimum wage, it’s worth around $50 to me, which means fuel might well have to rise to more than $15 a litre to get me out of the car.

This logic and analysis can be applied in many ways to any household that is not hand-to-mouth. A 2007 government-funded study concluded that public transport usage in New Zealand is less affected by external factors. Price is more important than any other factors.

Continue reading:

Will carbon emissions drop as petrol prices rise?

Given this, it’s a fairly safe bet that increasing fuel costs will not significantly reduce consumption and oil companies are unlikely to face significant consumer backlash.

Instead, household resources are being diverted away from elastic costs like food to pay for the higher fuel prices. The non-hand-to mouth households will feel a slight chill in upmarket cafes as the red line is reluctantly drawn through their daily afternoon latte.

Food banks that support hand-to mouth households will likely see a much more dramatic effect as they are called upon to bridge the gap between non-discretionary spending and minimum income in these stressed communities.

It’s a crisis, whatever the prime minister might say.