[ad_1]

Imagine going to hear your favourite orchestral piece played in a world-class venue – and only the woodwind and brass sections turning up. Whether we’re aware of it or not, this sparse soundscape is similar to what we’re often experiencing when we head out to our favourite parks or nature reserves. The sounds of the natural world are changing. This means that we are likely to experience more benefits from being in the outdoors.

There is growing recognitionSpending time in nature is good for our health and well-being. At the same time, we’re living through a global environmental crisis, with ongoing and widespread declines in biodiversity. This means that the quality of our interactions with nature – and the positive effects we receive – are also likely to be declining.

While all of our senses can help us experience nature, the most important is sound: sounds of natureHaving the power to increase mood, decrease pain, and reduce stress can make you happier. Our researchExplores the long-term effects of biodiversity loss and shifts in species’ habitatsClimate change is prompting changes in the soundscapes of nature.

Our research

Recordings of past soundscapes aren’t available from most sites. We needed to develop a way to reconstruct historical soundscapes so we could track how they’ve changed over time.

Bernard Dupont/Wikimedia Commons

To do this, we used the annual bird monitoring data collected through EuropeanAnd AmericanBird surveys have been conducted in more than 200,000 locations across North America and Europe. These surveys are conducted by a network of volunteer ornithologists in late spring and early summer and generate lists of which species and how many were counted at each site each year.

These data were combined with sound recordings from individual species to create soundscapes. Xeno-cantoA database online of bird songs and calls.

First, we cut all the sound files downloaded to 25 seconds. Next, we created a blank sound file of five minutes and then inserted the same amount of sound files to a species as were individuals. If there were five individuals of a particular species, we would insert five 25-second sound file of that species.

We were able to create a soundscape that represented the sounds of each species by layering the sound files. Listen to one our soundscapesBelow is a reconstruction of the data from 1998 at a location near Bromsgrove, Worcestershire.

Author provided2.29 MB (download)

To measure the characteristics of each soundscape, we used acoustic marker to create them. These markers allow us to quantify how the acoustic energy in each soundscape is distributed over frequencies and time. This allows us to measure how acoustic diversity has changed and how intense it is.

Our results show a steady decline in the acoustic diversity of soundscapes across Europe, North America, and Asia over the past 25 year period. This suggests that spring’s soundtrack is becoming more quiet and less varied.

We found that the sites with a greater decline in the number of species, or total number of individuals, also have greater declines of acoustic intensity and diversity.

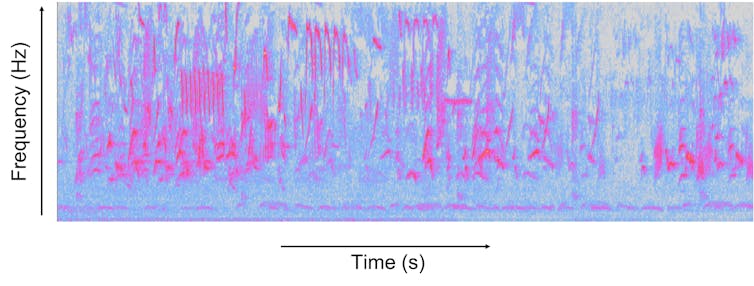

Below is a spectrogram that shows how sound energy spreads across a particular soundscape. The amplitude – meaning the energy or loudness – of bird noises is shown through colour, with dark blues corresponding to lower amplitudes (quieter sounds) and brighter colours like pink corresponding to higher amplitudes (louder sounds). The frequency can be described as the pitch or tone of a song. It is displayed on the y axis.

Author provided

It is important to consider how soundscape characteristics are changing by the way birds structure their communities as well as how different species’ call and song characteristics complement each other.

For example, the loss species such as the skylark (Alauda arvensis) or nightingale (Luscinia mygarhynchosThe loss of raucous music is more likely to have an impact on the complexity of the soundscape than a loss of rich, intricate songs by (). corvid or gull species. The exact impact of their loss will depend on how many individuals are still present and if other species have similar songs.

Our findings suggest that humans are losing touch with nature through chronic decline. Nature’s orchestra is fast losing both players and instruments.

We hope to raise awareness and encourage support by translating the hard facts about biodiversity loss into tangible images, recordings, and videos. conservationProtecting and restoring high quality natural soundscapes to ensure that people can enjoy and benefit from nature again.