COVID-19 – A late lesson from an early warning

2020 was a year both of voluntary and involuntary change thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there isn’t consensus on how SARS-CoV-2 became an infectious agent, Cheng and colleagues’ study has been accepted. As an example of early warning, Cheng et al. (2007) was cited. They wrote:

Coronaviruses are known to undergo genetic Recombination. This may lead to new outbreaks and genotypes. SARS-CoV-like virus reservoirs in horseshoe bats and the consumption of exotic mammals in southern China are a warning sign. SARS and other novel viruses that can be re-emerged from animals or laboratories should not be ignored. Therefore, it is imperative to be prepared (Cheng et. al., 2007, p.683).

Various governments and institutions have raised concerns in the past about the possibility of pandemics (EEA 2010, 2015), and some countries have developed plans and strategies. Following the 2009 pandemic of influenza A (H1N1), the World Health Organization warned the world that it was not well-prepared to handle a severe pandemic. (WHO, 2011). It was right.

Human progress is dependent on our ability to learn from the past. We can learn many lessons from the past, including how we deal with early warnings of human and environmental hazards. These lessons can be used to help create more resilient and better-prepared societies. EEA reports from 2001 and 2013 have described cases of unintended environmental dangers caused by chemical or other activities (EEA 2001, 2013, EEA 2013). These late lessons highlight the importance of precautionary measures and how to strike a balanced between uncertain environmental harms and desired economic opportunities.

The potential lessons from COVID-19 go much deeper than that. The COVID-19 pandemic serves as a stark reminder of how our identity is deeply intertwined with the ecosystems of the Earth. It is a concept that sophisticated societies have lost sight of: that we are part and parcel of nature.

Globalized societies are causing pandemics

Plagues and pandemics have been a part of human history throughout all time (Waltner Toews 2020). Pandemics can be caused by our globalized societies and economies today. This is due to the way we interact and interact with the natural world. There is no doubt that new pathogens can be created at the interface between wild and domestic animals and humans. These may sometimes manifest themselves as zoonotic illness (Figure 1). According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP 2020), 60% of all known infectious diseases in humans, and 75% of all emerging infectious disease, are zoonotic. In addition, at least six new coronavirus outbreaks have been observed in the past century.

Many factors interact to create new and varied contacts between wildlife, livestock, and people. This is how zoonotic disease can emerge. These include (1) rapid and uncontrolled growth in population, (2) increased demand for animal protein and consequently an increase in exploitation and trade of wildlife, (3) inadequate husbandry practices, (4) poorly managed informal wildlife markets and fresh produce markets, as well as (4) industrial meat processing facilities (UNEP, 2020). It is clear that pathogens can spread faster due to today’s high levels international trade and travel. Diseases can also move around the globe in shorter periods than their incubation period (UNEP 2020).

Although the origin and source of SARS-CoV-2 are not known, pandemics like COVID-19 may be the result of the mechanisms mentioned above. This is a striking example of how human health can be intertwined with the natural environment.

Figure 1: Pathogen flow at the interface of humans, livestock, and wildlife

SourceEEA (2020a), adapted by Jones et al. (2013)

These complexities in policy fields other than epidemiology, public health, and health are receiving more attention. Health crises such as COVID-19 can have profound implications for society and people. The Council of Europe recently discussed the relationship between pandemics as well as democracy, freedom of speech and the rule of the law. It reminds us that the COVID-19 crises should not be used to restrict the public’s access to information and that emergency measures taken in an emergency by Member States should not compromise the founding values of the EU of democracy, human rights, and the rule of the law (Council of Europe 2020).

The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, (EC 2020a), and the Farm to Fork Strategy, (EC 2020b) explicitly link COVID-19 to current levels biodiversity loss. The urgency that COVID-19 brings seems to open up a window of opportunity to raise awareness. Numerous researchers, activists, and commentators are discussing how the COVID-19 heightened awareness can be used to increase environmental awareness (Beattie, McGuire, 2020) or reframe economic models. (Barlow et. al., 2020; The Economist. 2020). This applies to both nation states and supranational organizations such as The Economist. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation(DG Research and Innovation, 2021). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD 2021) and a few others Important non-governmental organisations(for instance the European Environmental Bureau(EEB, 2021), which are involved with formulating post-COVID Transformation Strategies.

If there’s a will, there’s a way

COVID-19 has taught us one positive thing: Modern societies are able to use force when necessary (Mahmood, Sanchez 2020). New regulations can be quickly implemented, with some social practices and economic activities even being banned. If the reason is legitimate, schools, restaurants, sports arenas, and airports can be shut down overnight, provided it is temporary. EU Member States have been willing to take measures against COVID-19 which have had huge economic costs and created the risk of severe unemployment.

Can a similar level be achieved in order to achieve sustainability transitions (Scharmer 2020)? Strenuous measures are also justified by the World Health Organizations estimate that seven million people die annually from air pollution. COVID-19 makes it difficult to see how economic risks or the risk for recession can be used as arguments against environmental action and transformations towards sustainability.

The post-corona earth: Have we changed?

The global community will need to spend years, if certainly decades, assessing the full extent and implications of COVID-19 for our society, including the impacts on inequalities and health, and the well-being and well-being of citizens (EEA 2020b).

Unprecedented travel restrictions, national lockdowns and the closure of national borders in 2020’s first half have all contributed to short-term improvements in Europe’s environment. Air quality and noise levels were dramatically improved by a reduction in traffic, shipping, aviation, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2)2) in some cities declining by up to 60% compared with the same period in 2019 (EEA, 2020c). The pandemic had the immediate effect that it encouraged people to choose more active travel modes. Cities have become more bike-friendly, especially due to the increase in cycling (Kraus & Koch, 2021; Nikitas, et al. 2021). A decrease in human activity allowed habitats to recover, and species had the opportunity to occupy more space and niches (EEA. 2020d). Preliminary data also show that EU greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) decreased by 10% between 2019 and 2020 (EEA 2021a).

However, the increased demand for disposable protective and other equipment has led to an increase of plastic production and consumption, and therefore plastic waste (Ford 2020; EEA 2021b).

It is futile to try to restore the status-quo ante. (DG Research and Innovation 2021).

It’s not just citizens who have to change their ways. The pandemic and its socioeconomic effects required that policymakers quickly respond to them. NextGenerationEU is a recovery plan developed by the European Commission to help build a post COVID-19 EU that is more green, more digital, and more resilient to future challenges (EC 2021). The EU’s long-term budget and the amount of resources mobilized for climate and environment are unprecedented. This provides hope for a different future. One that is free from the old norm of unsustainable development. However, it remains to see if resources are invested effectively.

We should learn from our past experiences as a society. The 2008-2009 financial crises led to lower emissions but it was short-lived (Peters, 2012). There is no way to ensure that the post-corona planet, despite the need to emerge from economic recession, and the apparent resilience of unsustainable economic and political priorities, will be more sustainable unless there is a conscious, active, and conscious shift in social and economic practices.

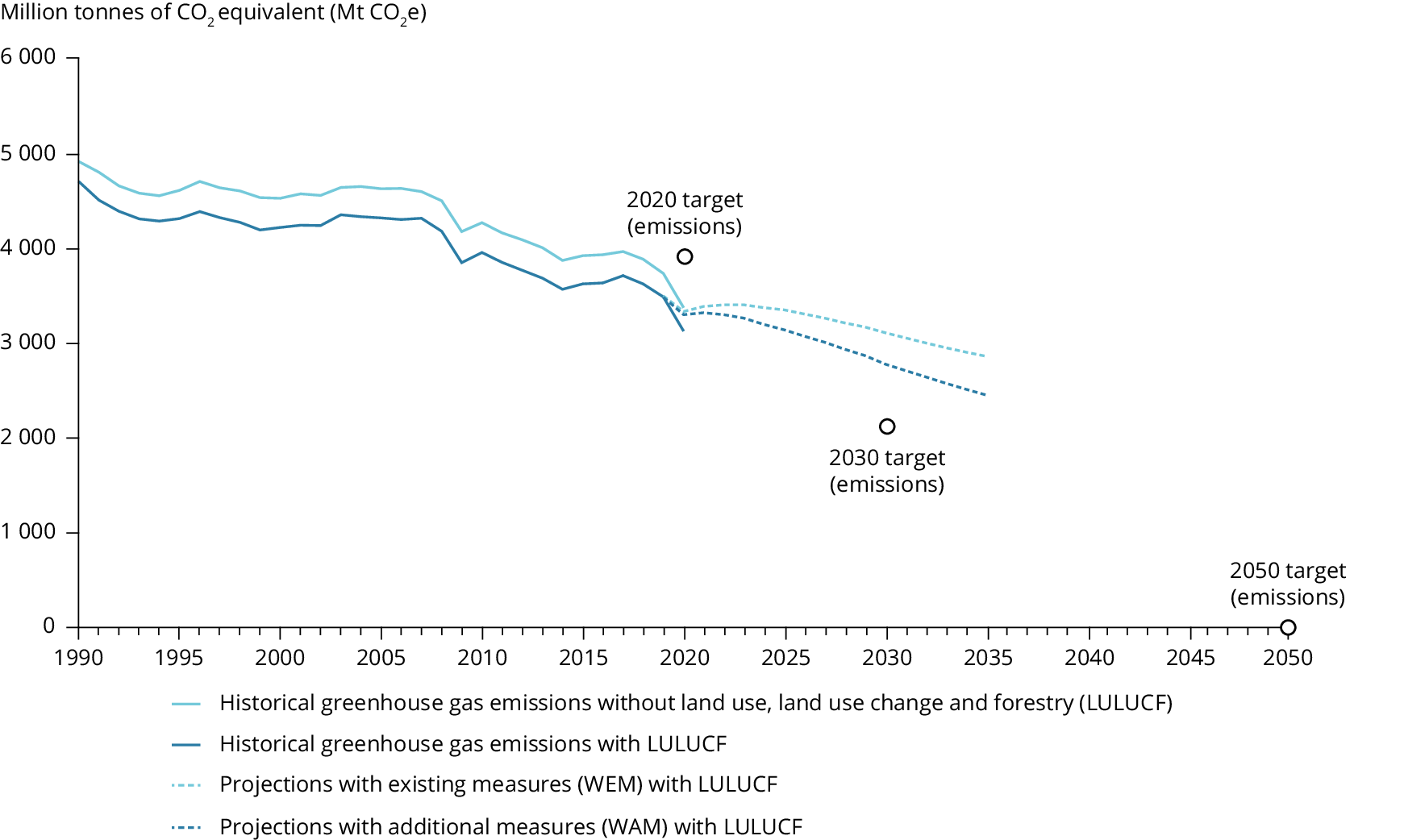

Early signs are not encouraging. The concentrations of airborne pollutant are rising with the resumption in economic and social activity. In some cases, they have returned to pre-pandemic levels (EEA 2020d). Warnings have been made about a rapid rebound of global energy demand and GHG emission post COVID-19 (IEA and Tollefson in 2021, 2021), whereas nationally determined contributions at a global level (Liu, Raftery in 2021) lack sufficient ambition to keep global temperature rise below 1.5C. Recent projections at the European level suggest that GHG emission levels could return to pre-pandemic levels if no additional measures are taken (Figure 2) (EEA 20,21a).

Figure 2 Historical trends, projections and estimates of greenhouse gas emissions

SourceEEA (2021c).

More information here

We have learned to deal with the pandemic and struggled with it. We had to change our daily lives, reorient our priorities, value things differently, and maybe appreciate the natural world more. But, it remains to be seen if we have really changed.

Change is now possible

The systemic fragility of our global economy has been exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic (EEA 2020e). It is not unreasonable to state that the world we live currently is characterized with multiple global crises. These include a health crisis as well as an economic and financial crisis. The history of pandemics has shown us that there are more pandemics to be expected (Waltner Toews 2020). We should at least be prepared.

COVID-19 serves as a wakeup call and a dress rehearsal for the future. []Our choices matter. This is what the pandemic taught us. Let us choose wisely as we look into the future. A. Guterres (2020), Secretary General of the United Nations

Cheng et. al.’s warnings should be taken seriously. (2007) seriously would mean considering a range of measures globally, including tackling illegal wildlife trade, closing down illegal food markets, tightening the regulation of industrial meat production, changing social and cultural food practices and, ultimately, changingunsustainable patterns of consumption, urbanisation and natural habitat destruction (IPBES, 2020).

The OECD (2021) highlighted that returning to business as usual would be missing a crucial opportunity to address interconnected economic, social, and relational issues that predate COVID-19. A well-being approach could be used to guide the process of building back a better (OECD, 2021), particularly if it is based upon the realization that environmental health and public health are prerequisites.

We don’t lack the ability to learn and have the ideas to act. Agency, the agency to address the driving factors behind these and other global crises, is the limiting factor.

Whatever form the next crisis takes, it will likely reveal itself as yet another symptom of the same underlying problem, unsustainable human production/consumption (EEA 2020e). It is this persistent problem that continues to show itself in challenges that can be framed either as issues that need to be addressed in premeditated political cycles or as crises that require extraordinary and urgent measures (Lakoff 2017). Our societies governance approach should address not only the root causes of the problems but also the increasing frequency or simultaneous emergence of what we used think of as exceptional crises.

Social and economic practices across all levels and aspects of society must change to address the sustainability crisis. Our lives, and the way that we eat, move, and power our societies, cannot be the same. The COVID-19 lockdowns forced Bruno Latour, a French philosopher and anthropologist, to reflect (Latour, 2020). He suggested that we reflect on the suspended activities that we would like to see end for good and resume them; what new activities or habits we would love to develop in the aftermath the pandemic; and how entrepreneurs or workers who are disenfranchised due to a reshaped economy might be able to transition into more sustainable or resilient roles.

This exercise can be done individually or at institutions. This exercise could serve as inspiration for further development and implementations of the European Green Deal.

COVID-19 led to a sudden and forceful response. Emergencies come with their own risks and dynamics, including those that affect democracy and legality. But, we have seen that where there is a will, there is a way. The extraordinary mobilisation and impact of COVID-19 response can inspire new ways of thinking that will help humanity seize this moment and make a difference. It seems reasonable to make significant changes in society to prevent COVID-22, or -25, from happening.

Acknowledgements

Authors:

Strand, R., Kovacic Z., Funtowicz S. (European Centre for Governance in Complexity).

Benini, L., Jesus, A. (EEA)

Review, inputs, and feedback:

Anita PircVelkavrh EEA, Jock Martin EEA, Catherine Ganzleben EEA), Claire Dupont EEA Scientific Committee, Tom Oliver (Reading University), Thomas Arnold DG R&I), Nick Meynen EEB, members of Eionet and EU Environmental Knowledge Community

Refer to

Barlow, N., et al., 2020, A degrowth perspective for the coronavirus crisisVisions for Sustainability14. pp. 24-31, accessed 17 Dec 2021.

McGuire, L., 2020. Coronavirus shows you how to get people to do something about climate change. Here’s the psychology, The Conversation 29 July, accessed 14 December 2021.

Cheng, V.C.C.C., and others. 2007, Severe acute respir syndrome coronavirus is an agent of emerging or remerging infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews20(4). pp. 660-694.

2020 Council of Europe The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon human rights and the rule-of-law our actionsaccessed 14 Dec 2021.

DG Research and Innovation 2021 Transformation post-COVID: Mobilizing innovation for people, planet, and prosperityESIR Policy Brief No 2, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (EC), accessed 16 December 2021.

EC, 2020a. Communication of the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. EU Biodiversity strategy for 2030. Bringing nature back in our lives (COM(2020),380 final, 20 May 2020).

EC, 2020b. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. (COM(2020) 381 final).

EC, 2021, The EUs 2021-2027 budget and NextGenerationEUEuropean Commission, facts and figures, accessed 10 October 2021.

2001. EEA. Late lessons from the early warnings: The precautionary principle 1896-2000. Environmental issue report No 22/2001. European Environment Agency. accessed 20 Dec 2021.

EEA 2010, Assessment of Global Megatrends, in The European Environment Agency’s Outlook and State 2010, European Environment Agency.

EEA, 2013, Lessons from early warnings: Science, Precaution, Innovation, EEA Report 1/2013. European Environment Agency. accessed 20 December 2021.

EEA, 2015: Global megatrends assessment expanded background analysis complementing SOER 2015 Assessments of global megatrends. EEA Technical Report No 11/2015, European Environment Agency. accessed 20 December 2021.

EEA 2019, Sustainability transitions policy and practice, EEA report No 9/2019, European Environment Agency. accessed February 7, 2020.

EEA, 2020a. Healthy environment, healthy people: How the environment affects health and well-being across Europe, EEA report No 21/2019, European Environment Agency. accessed 19 Jul 2021.

EEA 2020b, Together We Can Move Forwards: Building a Sustainable Planet After the Corona Shock, European Environment Agency, accessed 15 June 2021.

EEA 2020c, Air Pollution goes down as Europe takes strict measures to fight coronavirus. European Environment Agency. accessed 25/03/2020.

EEA, 2020d and COVID-19, Environment Agency. accessed 11 September 2021.

EEA, 2020e. Living in a state that is multiple crises: climate, health, economy or systemic sustainability?, European Environment Agency. accessed 22/09/2021.

EEA, 2021a. EU achieves 20-20-20 Climate Targets. 55% reduction in emissions by 2030 is possible with more efforts and policies. European Environment Agency, accessed 4 November 2021.

EEA 2021b, COVID-19 Europe: Increased Pollution from Masks, Gloves and Other Single-Use Plastics, European Environment Agency. accessed 6July 2021.

EEA, 2021c. Trends and projections for Europe 2021. EEA Report No 13/2021. European Environment Agency. accessed 6 December 2021.

EEB, undated, Corona crisis measures to build a better tomorrow: Turning fear into hopeEuropean Environmental Bureau, accessed December 20, 2021.

Ford, D., 2020, COVID-19 has contributed to the increase in ocean plastic pollution. A drastic increase in the use of gloves and masks, along with a decline of recycling programs, are threatening the health the seas.Scientific American, 17 August, sec. Opinion,accessed 15September 2020.

Goldstein, J.R. & Lee, R.D., 2020. Demographic perspectives regarding the mortality of COVID-19 or other epidemicsProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America117 (36) pp. 22035-22041.

Guterres, A., 2020. Address to the 75th General Assembly Session Opening of the General DebateRetrieved 6 June 2021.

IEA, 2021, Global Energy Review 2021accessed 5 October 2021 by the International Energy Agency, Paris

IPBES, 2020, Workshop report on biodiversity and pandemics from the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Daszak, P., et al., IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

Jones, B.A., and others. (2013). Zoonosis emergence related to agricultural intensification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America110 (21), pp. 8399-8404.

Kraus, S., and Koch, N. 2021, Provisional COVID-19 infrastructure causes large, rapid increases cycling, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118(15), E2024399118.

A. Lakoff. 2017, Unprepared: Global Health in a Time of Emergency, University of California Press Berkeley (CA).

Latour, B., 2020, What protection measures can you suggest to prevent us from returning to the pre-crisis production system??,accessed 5October 2020.

Liu, P.R. Raftery, A.E. 2021 To meet the 2C target, the country-based rate for emissions reductions should be increased by 80% above national contributionsCommunications Earth & Environment2, 29.

Sanchez, Mahmood and M. R., 2020, Greta Thunberg claims that the Covid-19 response shows that the world can suddenly act with the necessary force, CNN, 20June,accessed 17 December.

Nikitas, A., et al., 2021, Cycling in the era of COVID-19: lessons learnt and best practice policy recommendations for a more bike-centric future,Sustainability13(9), 4620.

OECD, 2021, COVID-19 and well being: Life in the pandemicOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Publishing. Paris.

Peters, G.P., et al., 2012, Rapid growth of CO2After the 2008-2009 global financial crises, emissionsNature Climate Change 2(1): pp. 2-4.

Scharmer, O., 2020, Eight lessons to learn: from climate action to coronavirusRetrieved 17 December 2021.

The Economist 2020 The Covid-19 pandemic is requiring a rethink of macroeconomics,accessed 25July 2020.

Tollefson, J., 2021, Following the COVID pandemic dip carbon emissions quickly reboundedNature, accessed 17 December 2021.

UNEP, 2020, How to prevent the next pandemic of zoonotic diseases, and how to break the transmission chainUnited Nations Environment Programme, accessed 17 Dec 2021.

Waltner-Toews D., 2020. On pandemics. Deadly diseases from bubonic and coronavirus. Greystone Books. Vancouver, Canada.

WHO, 2011, Implementation International Health Regulations (2006): Report of the Review Committee for the Functioning International Health Regulations(2005) in Relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009., A64/10, World Health Organization,accessed 13October 2021.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 20/2021

Title:COVID-19: Lessons for sustainability

HTML – TH-AM-21-020-EN-QISBN 978-92-9480-423-5ISSN2467-3196 – doi:10.2800/320311

PDF – TH-AM-21-020-EN-NISBN 978-92-9480-422-8ISSN2467-3196 – doi:10.2800/289185