[ad_1]

OThe sky is grey and the mood is dark when I meet Ed Miliband at his large Victorian home near Hampstead Heath. He just returned from Westminster, where he gave Vadym Prystaiko, Ukraine’s ambassador to London, a long loud and arduous welcome. standing ovationThe sound of it is still ringing in his ears. “I don’t care much about what the House of Commons does and doesn’t do,” he says, when I ask if this was touching (convention has it that the chamber doesn’t indulge in applause). “But yes, it was incredibly moving. Normally, I never go to PMQs because of the obvious: PTSD… and it’s sort of rubbish. But I wanted there [today].” So prime minister’s questions is still a trigger for him, is it? It was a long ordeal that required three Valium and many gins. He laughs. “Yeah, that sort of thing.” But I shouldn’t joke. He says that the atmosphere at Westminster is one of shock. “I was talking to a Tory MP on the way in – I talk to Tory MPs quite a lot – and everybody feels… To see this happening on our doorstep, such a brutal act of aggression.”

Is he afraid of the worst? He hesitates. “As in?” I mean, does he worry that this war is going to be extremely bloody and protracted? Hmm. Hmm. It’s seven long years since he I have resigned from this jobHe was wearing jeans today, which was supposed to bring about liberation. But old habits die hard. His second thought, if it is not his first, concerns how the conflict will impact his role as shadow secretary for state for climate change. “One thing that’s encouraging is that Europe, the US and Britain have acted on sanctions. They didn’t just go through the motions; they did a lot more than that. Even on energy. Europe is reliant on Russian gas,They’re thinking: how do we diversify out of this? There is a real will to do everything possible economically.” The transition to clean energy is going to have to happen much faster, and go much further, whether Nigel Farage and the Tory right like it or not: “It’s not just a climate case. It’s an energy security case.”

He agrees that the war will likely result in major policy shifts in domestic politics, including in the way the parties discuss Europe. But, Brexit-loving voters in Doncaster are unlikely to hear anything that could scare the horses as far as the EU is concerned. “We’re not reopening the remain/leave question,” he says. “We’re talking about international alliances. I think there’s massive public sympathy [for Ukrainian refugees]. But will it change people’s minds about Brexit? Brexit goes so much deeper than people’s views about Europe. It’s about their sense that society hasn’t worked for them for a long time.” All the same, isn’t it striking – if this is the word – that Ukraine might be about to Join an organizationHow did Britain leave so recently? What does this tell him? “It’s really important for us as a party to fight for building international alliances,” he replies, not really answering the question. Does he regret his decision? Vote against military action in Syria2013? (The horrors Putin unleashed in Russia were foreshadowing what is happening now in Ukraine. “I have no regrets. It was a hard decision, but I don’t think it was a wrong decision. I wasn’t confronted with a plan for military action, but a plan for bombing; no sense of strategy. It wouldn’t even have taken out Assad’s chemical weapons.”

But let’s leap back, briefly, to the transition to green energy. He thinks it’s absolutely the case that those who felt they couldn’t afford to invest in, say, a Heat pump and new insulation six months ago will be even more reluctant now the cost of living is set to rise even more dramatically – but that this is half of his point. “This is an incredibly important thing, you see!” he says, leaning forward, as if into a sharp wind. “My critique of the Tories is not just that they say they’re going to do stuff, and then don’t deliver; it’s that they really think this is going to be market-led. That is not climate denial. It’s that people will think: is this going to be fair?” Luckily, Labour has the answer in the form of its Green New Deal: a £28bn investment pledgeIt is more than 1% in the UK GDP. “We’re not going to say: let’s have the unjust carbon world, and the unjust zero-carbon world. We’re going to say: there is a chance for transformation. If there is an obligation to act,This is also an opportunity.” At this last thought, he smiles: a grin of such radiance, it could probably power his central heating. “And this is why I’m still in politics.”

Miliband’s Recent book Go Big – to me, a rather unfortunate title; I can’t help but hear someone at Burger King shouting it as they wave the prospect of a Whopper at a customer – is full of moments like this, hope trying desperately to wrestle experience to the floor. Based on Reasons to Be Cheerful, the podcast he co-hosts with the radio DJ Geoff Lloyd (with whom he’s having a self-confessed, passionate midlife bromance), it aims to find solutions to society’s most intractable problems, from disillusionment with democracy to the housing crisis, from low pay and long working hours to gridlocked cities. The problem is that despite having tried to inspire excitement in the readers about such ideas as universal basics income (a sum paid every citizen by government) or free bus for all (as instituted by the Dunkirk mayor in France), there inevitably comes a moment of crushing anticlimax when he admits that, financially speaking, the sums don’t quite add up. UBI, for instance, is unlikely to appear in a Labour manifesto any time soon: “UBI replaces a welfare system that is dishonest and bad and mean; in tests, it hasn’t made people reluctant to work. But then, yes, you look at the numbers.” Still, it is, he believes, an idea that deserves to be kept alive: “The NHS was first talked about in 1909, and it didn’t come into being until 1948.”

He says politics is all about faith. He still has as much of it as he does hair on the head (which is to be said: a lot). Ostensibly, his reasons for deciding first to stay in parliament, and then to serve in Keir Starmer’s shadow cabinet, are straightforward. “If I get to be climate change secretary in the next Labour government, there’s nothing bigger than that,” he says. But don’t most people still look at him and wonder why he isn’t despondent, worn out? What a glutton to punish. Most ex-leaders are quick to gratify. “Yes, it’s interesting. It is very unusual.ishIt is possible, however [William] Hague stayed.” Miliband knew “immediately” that he would. “I didn’t have that much doubt. We returned to London [on election night, 2015]In the middle of night, we left and went on to the Monday [he and his wife, the high court judge Justine Thornton; they have two sons]Ibiza. It was a good thing to do, but it’s not about a few days… it takes… a long time [to recover from such a failure]. Purpose is the best antidote. I felt a deep sense of responsibility that I lost the election, but I also felt I could fight for my ideas.”

But it must be psychologically difficult, I say: Serving under Starmer. “You would be right,” he says. “It’s difficult, but it’s also easier, because I know what it’s like [to be leader]. I sympathize with anyone who is the leader or the co-leader of the Labour party. It’s a nightmare. I remember talking to Keir before he got the job.” Did you warn him? “Yes, I’m sure I did. I went to a fundraiser Neil Kinnock did for me, and as I walked in, I heard him saying: I wouldn’t wish this job on my worst enemy. [At the time]It was truly a strange thing to say. [That’s because] nothing quite prepares you for it.” What was the worst thing about it? “The sense that every word you say is going to be parsed and examined, and the intrusion; the sense that it was very hard to be there for my family.” Hadn’t he imagined all that? “I think I had, obviously, but the gulf between being leader and not being leader in terms of 24/7 scrutiny is… Big.”

His departure ushered in, ultimately, the Jeremy Corbyn years – a disastrous period for the Labour party. Is the hard right now defeated? How united is the party right now? “I think it’s pretty united. I have a joke about Labour party. Most people say: let’s bury our differences. We say: let’s bury our similarities.” His argument is that while Corbyn was a bolder version of himself, other things – major things – also contributed to his election as leader: the financial crisis, Brexit, tuition fees; above all, the feeling on the part of many Labour voters that they had been left behind.

Starmer is now in a quandary. Those feelings haven’t gone away, but the supposed boldness was also catastrophic in terms of winning an election. “I think Keir is trying to be radical and credible; he’s trying to steer a course. I used to say [that such a course] lay between the rocks of ‘there is no difference between the parties’ and ‘we can’t trust you’.” What about the so-called Red wall? People who had voted Labour for generations in the north voted for the Tories. Now that the Tories are likely to fail them, is it credible that they will just revert back to voting Labour? This situation is politically dangerous, isn’t it? He nods. “Disillusionment,” he says. Then, he says, “Disillusionment.”

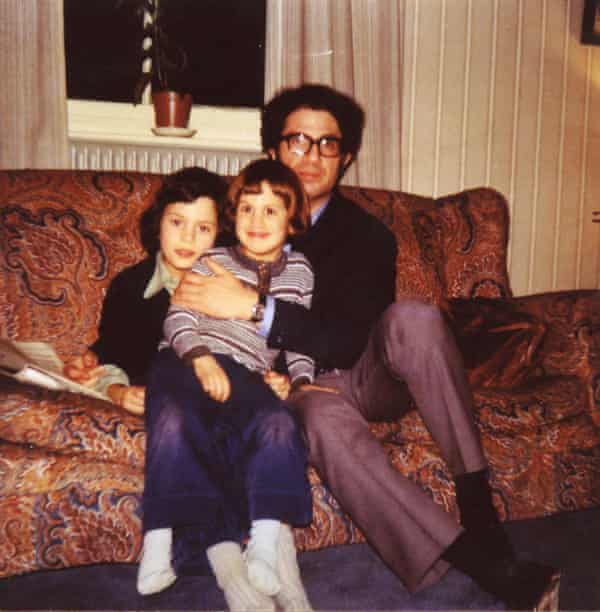

Miliband grew up in north London, not far from where we are now, a possibly somewhat precocious boy who was apt to “argue the toss with the slightly nonplussed friends of my parents who came round to dinner”. His father, Ralph was a Marxist academic. His mother Marion was a longstanding activist for human rights. Both parents arrived in Britain as Holocaust survivors. Does he feel the influence of his parents growing as he ages? This is one of the many discoveries of middle age for many: that we cannot escape our early familial diktats. He knows what I mean. In recent days, however, the television news has repeatedly reminded him about their history. “Dad was a Marxist, but it wasn’t Das KapitalFor breakfast. He was a great speaker about ideas. ‘History is on our side,’ he would say. He always had time to spend with us. I’m struck by that.” Did his parents expect a lot of him? (I can imagine their reaction to his teenage passion. Dallas.) “Yes, probably. Because they were refugees… they didn’t say this, but I feel it in retrospect… you’ve got a responsibility to make the world a better place. So many of their family didn’t make it.”

Did they tell him the Holocaust story? “No, no. They didn’t talk about it. My dad used to talk about going to Britain, but it was too painful to my mom. She’d lost her dad.” So how did he find out about it? “I went to Israel to see my [maternal]When I was seven years old, my grandmother showed me a picture of her husband. I asked who that was? But it was – what’s the right word? – an incremental thing.” His parents, he thinks, were both determinedly content and burdened by deep grief: “It’s paradoxical.” What was it like to see so much antisemitism in the Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn? “Terrible. One antisemite is not enough. Keir has the right idea to deal with it. He has made a lot of progress in dealing with it.”

Miliband doesn’t know what the next couple of years will bring, though he thinks that the scandal that is Partygate has been overtaken by events; the prime minister’s survival is now far more likely. David, his brother, is he ever going to return to Britain, against whom he stood so ruthlessly as Labour leader? (He is the CEO of the International Rescue Committee in New York. “I don’t know. He’s doing a very important job.” But whatever happens, the party that wins the election will be the party that is best able to “paint a picture of the future”, and this means he is very busy himself: lots of meetings, the hoovering up of expertise.

He does have more time these days. The frontbench is a more hospitable realm than the leader’s office: “You don’t feel you’re always carrying a Ming vase across the ice rink.” In the pandemic, he learned to ride a bike and grew his mild obsession with cold water swimming. “It’s very boring when people go on about cold water swimming, and I am very boring about it: how long I lasted, the fact that it was four degrees.” He has all the kit: a special hat, gloves and socks. “And I wear trunks, too, obviously. It’s my midlife crisis.” He does it twice a week, up the road – and yes, once, someone did try to take a photograph. What else? Books? Theatre? He hasn’t been out much: “I’ve been quite Covid anxious.” But at Christmas – bloody months ago! – he did manage to read one of Richard Osman’s novels.

Getting up to go, I’m struck by how strangely impersonal his sitting room is, as if all the nicknacks have been removed ahead of my arrival (perhaps Jonty, his aide, who for no good reason that I can see has sat in on our conversation, was tasked with this job, too). A game of Through the Keyhole would be quite impossible here, though as I stand up, I can see, out of the window, a lawn and a trampoline and…

Suddenly, I’m all excitement. I’m wondering about The Ed Stone, that hubristic folly with which, in our house, we’ve been fixated ever since the Daily MailThe person who could find the Ed Stone, which contained six unaccountable 2015 election promises, was promised a case champagne. Is it still there, trailing the ivy? Alas, it isn’t. “I don’t know where it is,” says Miliband, good naturedly. “I wish I could say it’s in my toilet, but I think it’s smashed up somewhere. If I find it, I’ll let you know.” It should really be on display somewhere, I tell him; wouldn’t the People’s History Museum in Manchester take it? To which he can only reply, faux-downcast: “Great. Serve as a warning.”

-

Go Big: How to Fix the World by Ed Miliband is published in paperback by Bodley Head on 17 March (£9.99). Please support the GuardianAnd ObserverGet your copy now guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply