[ad_1]

IRELAND’S MAIN CLIMATE goals – to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030 and to reach net-zero by 2050 – are focused on trying to mitigate or prevent the worst impacts of climate change.

Some of the negative effects of climate change, such as extreme weather events and other natural disasters, are already being felt in the United States and around the globe.

The major component of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) next report will be devoted to adaptation. This authoritative assessment of climate research is authored by hundreds from around the globe.

The Irish government will update their National Adaptation Framework for 2018’s first time in 2022.

The framework will need to address deficiencies in Ireland’s climate adaptation policies after the Climate Change Advisory Council (CCAC) recently warned that multiple sectors have made Very little progress has been made towards securing themselves against climate change..

As we start a year of important developments in climate adaptation, here’s a look at what it is, what the government is – and should – be doing, and what we can expect from the IPCC report.

Protecting the vulnerable

In 2018, the government published Ireland’s first National Adaptation Framework, which aimed to “reduce the vulnerability of the country to the negative effects of climate change”.

However, most sectors are not adequately prepared to deal with the climate crisis’s threats.

“Adaptation is ensuring that the systems and structures that we depend upon are resilient to the impacts of climate change, so it’s about reducing the impacts that are already being felt and will be felt in the future,” Professor Conor Murphy, a lecturer in Maynooth University’s Department of Geography and adaptation expert, told The Journal.

“The nature of climate change is that we are currently committed to impacts and impacts are happening, so adaptation is what we do about them,” Professor Murphy explained.

What’s critically important is that adaptation is not just about scientific projection of the impacts of climate change, it’s about understanding social vulnerabilities and what makes people vulnerable to loss as a result of climate change in the first place.

“That’s what makes adaptation difficult – it’s not just making scientific predictions about how targets are going to be met, it’s about sustainable development, it’s about justice in terms of decision-making and how communities can be brought along.”

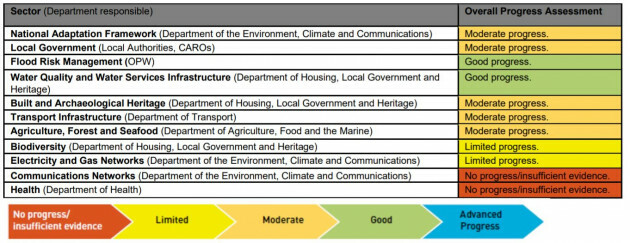

In its recent Annual reviewThe CCAC published a scorecard that looked at the progress made by specific sectors in climate adaptation.

Some sectors are better prepared than others, but it was not possible for the Council to give each sector the highest possible score within its ranking framework.

Source: Climate Change Advisory Council

Flood risk management, water quality, and water services infrastructure were rated as having made good progress. Local government, heritage, and agriculture were deemed to be making moderate progress.

The CCAC did not find any progress in the areas of health and communications networks and only limited progress in electricity, gas, and biodiversity.

“For health, I know the priorities have been elsewhere for the last couple of years, but when it comes to the impacts of climate changes, there are the direct impacts from things like floods and extreme heat, but also the indirect impacts. How does place loss, for example, impact on mental health for people?” Murphy said.

“We’ve done some work in Courtown in Co Wexford where loss of the beach is having impacts on people in terms of possibilities for recreation and wellbeing associated with loss of place,” he said.

“In terms of communications networks, we’ve seen how vulnerable we are to storm events.

“The impacts probably weren’t as bad as they could have been with Storm Barra, but [we need to be] thinking about what those exposures are and what can be done to ensure that systems we so heavily depend upon in our communication and energy networks are robust to changes in extremes, whether that’s flooding, storms, whatever the case may be.”

Courtown, Co Wexford, where erosion has reduced the sand at the beach

Source: Alamy Stock Photo

The National Adaptation Framework

The Climate Action Plan, which was established in Ireland, is Published November outlines that the National Adaptation Framework is due to be updated in 2022.

The Department of Environment and Climate will open a public discussion on the current framework during the first three months of this year.

That’s due to be followed by a report to Minister Eamon Ryan on the results of the review process by the autumn.

Professor Murphy said there are “a number of challenges with adaptation across sectors, particularly coastal and marine, which doesn’t fall clearly under one jurisdiction in terms of responsibility”.

“Also, looking at the cascade of impacts and the interactions around adaptation in between different sectors has been challenging so far,” he said.

“I think those are two areas that the updated framework needs to take account of, including sectors that are not already there, and looking at collaboration across different sectors to ensure that adaptation in one sector is not undermining efforts in another.”

‘Governments have to listen to it’

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC), is expected to publish its second cycle report in February. This report will focus on climate adaptation and impacts.

The IPCC, a United Nations body that includes 195 member nations, includes Ireland, engages hundreds to produce reports summarizing the results of recent climate research worldwide for policymakers.

It’s moved through six assessment cycles since it started its work back in 1990. The AR6 report, which was the first working group in the current cycle, was released last August. Climate change: Physical science.

Now, the report from AR6′s second working group (ARG WG2) will hone in on adaptation and how resilient or not the world is to the climate crisis.

Climate protest in Stockholm, Sweden

Source: Shutterstock/Frederick Hornung

Professor Mark Costello is a scientist from Ireland currently working at Nord University in Norway, and he’s one of the lead authors of the AR6 WG2 report.

Talk to The Journal, Professor Costello said that the “whole process behind IPCC and the key thing that makes it different from some other assessments is that the governments decide what the chapters will be and the chapter headings”.

He said that the governments “have to approve the final report as well” and can make comments before it is published.

During that process, some said that “Brazil and Russia and some other countries were making comments to try to tone down literature, but I didn’t really see it that much to be honest”.

“I think they were all presented as arguments that they had, that they didn’t like the use of this terminology and, in many cases it was jargon, in a way, and what may be jargon in one country, like ‘nature-based solutions’ or ‘ecosystem’ and ‘adaptation’, might mean something different to another group of people in another country.

“But because of that government endorsement, it means governments have to listen to it.

It’s like going to the doctor and you’ve paid him to do something and he gives you his recommendations. It may not be something you like, but it is still important that you listen to it.

The report’s full text is over 2,000 pages. A summary for policymakers is also included.

“Most of it is really heavy reading. You’re required to put in ‘certainty’ language [which tells the reader how certain the science is on a particular point] and it really stuffs up your paragraph because you have to have all these bits in brackets, and the citations, codes, referencing – it has to be traceable, the traceability – so it almost becomes a quasi-legal sort of document.”

Bad news is not news

Support The Journal

Your ContributionsWe will continue to be supported by your support

To tell the stories that matter to you

The bar for what the report will refer to as “virtually certain”, “very likely” or “likely” is much higher than how those terms would be used outside of a scientific context.

Professor Costello said that looking at previous reports, the process is “inherently conservative”.

“Even though many of the authors might think things are going to be worse or are worse, at least in some situations, they can’t say so without evidence,” he said.

“We can’t speculate based on the absence of evidence or have to be really, really careful if we do so. Scenarios is one way of doing that, saying if it warms by four degrees, it’s way worse than three degrees, which is worse than 1.5.”

From his work in biodiversity, he said that on climate adaptation, leaders “should be doing the things they’ve long promised to do already but haven’t delivered on”.

They’re not really following through on a lot of the environmental protections they were supposed to, like water quality. They’ve been doing a little bit, but they really need to ramp it up.

“Compared to infrastructure costs, these things are cheap and they can employ people and they make it a better quality of life for everybody and the country as a whole.”

He said that the world was “going to have to change our habits anyway, but now climate change makes it much more urgent”.

“Adaptation is really changing with the view to improving life for everybody and improving the economy. It’s like a lot of these other changes like smoking and recycling and all these other things that people have done.

“Every time somebody suggests anything about change, you always get the naysayers.

“It’s a matter of change and people are always uncomfortable with change. This is a new change that has to be done globally because it’s affecting the whole planet.”

[ad_2]