[ad_1]

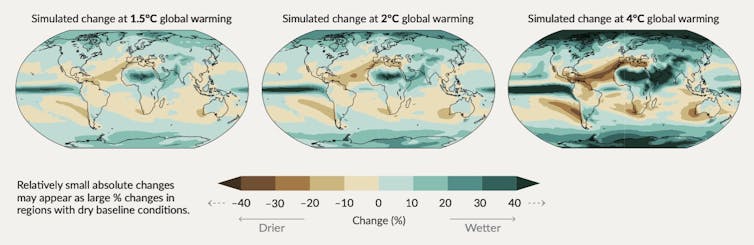

The Arctic will receive more rain than snow for the first time in a whole year before the end this century. That’s one of the key findings of a new study on precipitation in the Arctic which has major implications – not just for the polar region, but for the whole world.

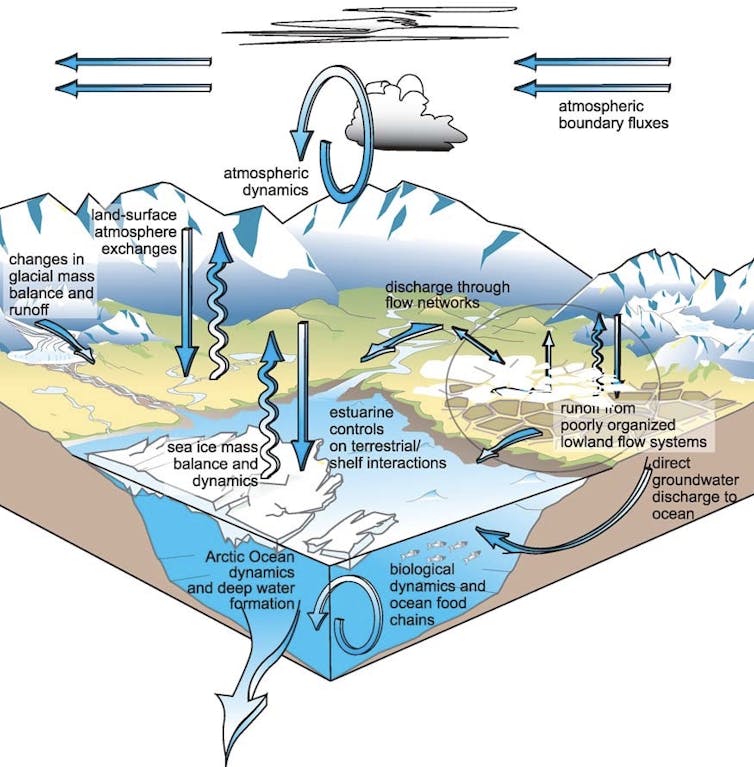

Although a reduction in frozen ocean surfaceThis is one of the most well-known impacts of Arctic warming. However, it has been long anticipated that a warmer Arctic would also be wetter, with more intense water cycling between land, atmosphere, and ocean. The ability of the Arctic to retain more moisture in warmer temperatures, increased evaporation rates from ice-free oceans and a relaxing jet stream are all factors that drive the shift from a frozen area to a warmer, wetter Arctic.

Vörösmarty et al., 2001

Although the timing of this shift is uncertain, it is likely that the Arctic water cycle will change from being snow-dominated to becoming rain-dominated. uncertain. A team of scientists has published a study in the journal. Nature CommunicationsThis suggests that the shift will occur sooner than originally thought. The effects will be most pronounced in autumn with the Arctic Ocean, Siberia, and Canadian Archipelago becoming more rain-dominated by the 2070s than the 2090s.

Warmer and wetter isn’t necessarily better

This dramatic change in Arctic water cycles will have a direct impact on ecosystems on both land and ocean. You might intuitively expect that a warmer and wetter Arctic would be very favourable for ecosystems – rainforests have many more species than tundra, after all. However, the Arctic’s plants and animals have evolved to survive in cold environments over millions of years. Their relatively simple food web is susceptible to disruption.

Warmer temperatures can lead to larval insects emerging earlier than the fish species that eat them. More rainfall means more nutrients are washed into rivers. This should benefit the microscopic plants at base of the food chain.

However, this can make rivers and coast waters more murky and less light-sensitive, which can lead to photosynthesis being impeded and possibly clogging filter feeding animals such as sharks and whales. Brackish water supports fewer species than freshwater or seawater. Increasing freshwater offshore may be a good idea. reduce the rangeArctic coasts, plants and animals

Guy Tallentire, Author provided

There are more reasons to doubt the benefits of warmer temperatures, greater freshwater circulation further into the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic surface waters are alkalinized due to the dissolved components of rain, river water, melting ice and snow. This makes it difficult for marine organisms construct shells and skeletons and limits chemical neutralisation. CO₂ absorbed in seawater.

At the same time, rivers flowing through degrading permafrost will wash organic material into the sea that bacteria can convert to CO₂, making the ocean more acidic. Fresh water also floats on denser oceanwater.

The ocean becomes stratified, limiting the exchange of nutrients and organisms between deep sea and surface waters, and reducing biological activity. Although the likely effects of a warmer, more humid Arctic on food webs and biodiversity, as well as food security, are not known. However, they are unlikely to have a uniformly positive impact.

The Arctic is a decade ahead of the global averages

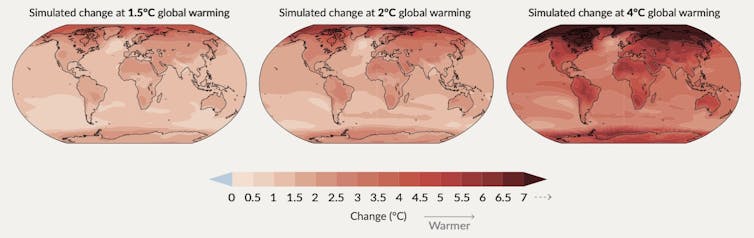

The Arctic has seen temperature increases that are faster than the global average. This will only be reinforced as snowfall is reduced and rainfall increases, since snow reflects the sun’s energy back into space. The land will become less reflective and snowy, so it will absorb more solar energy and warm up. The Arctic is predicted to continue warming faster that other areas, further reducing the temperature difference between the warmest part of the planet and the coldest. complex implicationsFor the oceans, and atmosphere.

IPCC 5th Assessment Report, CC BY-SA

IPCC 5th Assessment Report, CC BY-SA

The recent COP26 climate summit in Glasgow focused on efforts to “keep 1.5°C alive”. It is worth remembering that the 1.5°C figure is a global average, and that the Arctic will warm by at least twice as much as this, even for modest projections.

The new study underscores the importance of the global 1.5°C target for the Arctic. For example, at this level of warming Greenlandis expected to shift to a rain-dominated climate for most or all of the year. While at 3°C warming, which is close to the current pathway based on existing policiesInstead of making promises, most Arctic regions will transition to a rain-dominated climate by the end of this century.

It’s research that adds further weight to calls for improved monitoringArctic hydrological system and to the growing awareness about the immense impacts of even small increases in atmospheric warming.