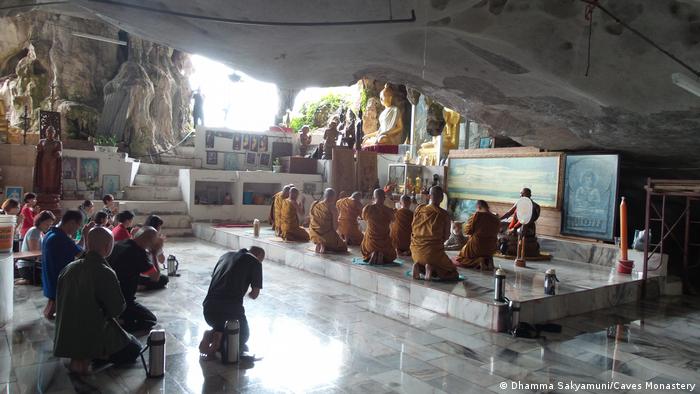

Cool breeze blows through the Dhamma Sakyamuni Monastery. The polished stone floor is a perfect place for monks to sit cross-legged and meditate quietly under the gaze of a Buddha in gold. The ceiling of rough limestone is covered with stalactites.

This is one of the few remaining limestone cave temples from Malaysia. It is nestled at the foot Mount Kanthan, one the 12 limestone hills rising up from the Kinta Valley of Perak in Malaysia. These caves are home to 15 Buddhist monks who live and practice their faith.

The peace is fragile. You can hear the sound of explosions echoing through the valley, akin to gunfire. This is the sound of dynamite being used to blast limestone from nearby peaks to extract it for cement.

Since the 1960s, Mount Kanthan has been leased by Perak’s state government to Associated Pan Malaysia Cement. The mountain has been divided in four zones, two which are being quarried already. The contrast is striking: The richly wooded southerly zones contrast with the barren expanses made of pale rock, rubble, and other quarried zones to their north.

AMPC is currently applying for permits to start work in one of the so far untouched areas, where the monastery is located. First, it must expel the monks from the monastery. They are not legally allowed to be there.

A spiritual sanctuary

Mount Kanthan, a stunning example of karsttopography, is where soft, porous limestone has naturally been eroded to create sculptural networks that include valleys, caves, and sinkholes. These areas are home to many species of animals and plants that are adapted to them, and they have been a popular place for humans.

Bhante Kusala believes that few people would want to live in caves, but hopes that the sanctuary will be declared a cultural heritage site

Bhante Kusala, a monk, manages the monastery along with other monks. It was founded by Master Fu, who was attracted to Mount Kanthan’s form like a reclining Buddha.

Kusala said that the founder chose to mediate in this serene, peaceful environment because of its ancient tradition of Buddhist monks seeking harmony in the natural world.

The gentle sound of water running from the ceiling’s stalactites fills the monastery. The monks can bathe, wash their clothes, and clean the temple’s floors using the water that is captured by a system of pipes.

Seongyee is an volunteer who has been volunteering at Sakyamuni Caves Monastery cleaning and maintaining the monastery for the past five years. She says, “This is a spiritual sanctuary to us.” “We rely on it; this part of the spiritual path we are on.”

Endangered species

If the cement company wins, it will not only be this religious community that could lose its way of living. Ruth Kiew, a botanist working with the non-profit Malaysian Cave & Karst Conservancy among other organizations, told DW the destruction of the entire mountain could result in the extinction of critically endangered fauna like trapdoor spiders or bent-toed geckos.

Kiew will be celebrating its 40th anniversary in 2014. Published a studyThe quarrying at Mount Kanthan has threatened the flora, with 32 species of conservation importance, 12 of which are endangered. Three recently identified speciesTree believed to only grow on Mount Kanthan

APMC and its parent company, YTL Construction Corporation, declined to be interviewed by this reporter. However, according to Website of YTLThe company has been working closely with the Malaysian non-profit, the Tropical Rainforest Conservation and Research Centre. This is to help Mount Kanthan’s threatened flora at a dedicated nursery.

TRCRC spokesperson told DW that the goal of the project was for YTL to be able to run their own conservation nursery and collect seed. They also wanted to teach them the basics of tree planting.

It is unclear if YTL is using knowledge gained from this project to continue conservation efforts. Scientists warn that even a small portion of Kathan Mountain habitat could lead to unique species being lost forever.

Kiew stated that “even different parts of the hill due to varied topography still harbor unique habitats or specialist species.” He also said that “plants and animals are not evenly distributed over the karst hills.”

Yong Kien Thai, a botanist from the University of Malaya, has visited the mountain multiple times to observe its biodiversity.

He says, “They may eventually grow some species originating from limestone, but they didn’t explain where they would replant them.” “Reintroduction is also problematic because each limestone hill has its own set of diversity.

Cultural heritage is in balance

Kusala believes that his community of monks is the “custodians” of this mountain, and that they live in harmony with these unique ecosystems.

APMC filed a January 2021 order with the court to evict Mount Kanthan residents. It referred to the monks in the order as “unidentified occupants occupying land” and stated that they were there “without consent, authorization, and/or permission of the company.”

Leong Cheok Kenneng, a spokesperson for the monastery said that six of the monks had now filed to be acknowledged as official parties in this case. This means that they have more control over how their legal argument will be shaped.

They are also trying to get the monastery declared a cultural heritage site. Before the pandemic, devotees would travel from cities like Kuala Lumpur and other places to the Sakyamuni Caves to practice cave meditation.

The Ipoh City Council, Perak’s administrative capital, sent a letter of support to the monastery in late December 2021. The council supported the designation of the land as a cultural heritage site.

Leong states, “If the monastic site is declared a heritage site, it means that nobody can alter the structures there and the site is protected against being damaged.”

Kusala radiates equanimous humor. He is aware that this way to live is in jeopardy as the monastic values he represents are competing with his economic interests. He laughs and says, “Nowadays not many people want monks.” “They don’t want to live in caves and forests… We are the rarest species!”

Edited By: Ruby Russell