[ad_1]

According to data provided by the US, agriculture is the leading source of methane.

According to data provided by the US, agriculture is the leading source of methane.

Image: Shutterstock

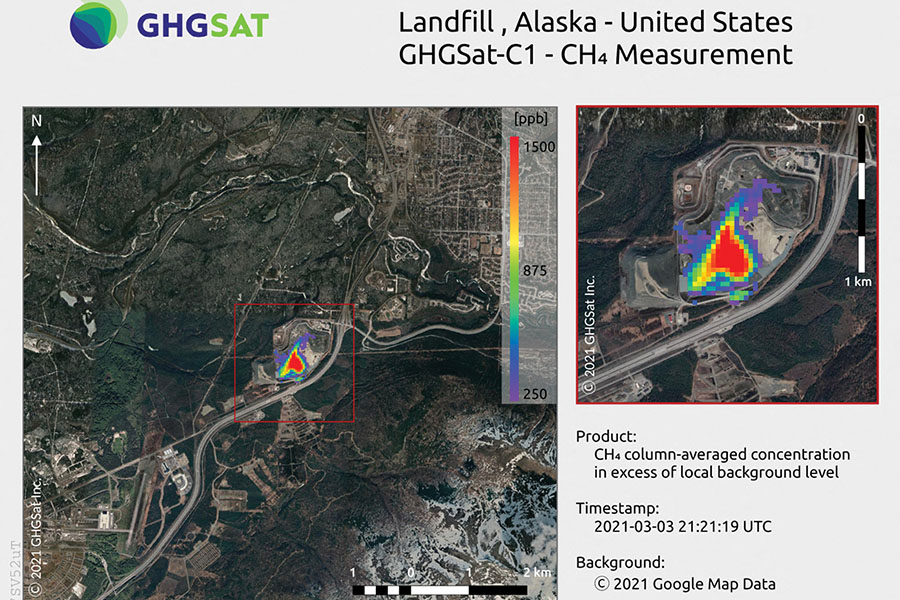

ISatellite Iris, a satellite that was launched by GHGSat (Canada) in September 2020, witnessed her first methane plume over Turkmenistan, Central Asia. There was joy. The screen displayed a rainbow display of vibrant colours that demonstrated human ingenuity. Iris was able to identify individual sources of methane, down to individual oil- and gas facilities. Methane emissions, which contribute to climate change, can be observed at 25 metres resolution.

ISatellite Iris, a satellite that was launched by GHGSat (Canada) in September 2020, witnessed her first methane plume over Turkmenistan, Central Asia. There was joy. The screen displayed a rainbow display of vibrant colours that demonstrated human ingenuity. Iris was able to identify individual sources of methane, down to individual oil- and gas facilities. Methane emissions, which contribute to climate change, can be observed at 25 metres resolution.

Iris isn’t the only one there. Pascal Peduzzi, director, United Nations Environment Programme / Global Resource Information Database-Geneva (UNEP/ GRID-Geneva) shares on email: “We are also in a project for using [Satellite] Sentinel 5 for data on certain gas including methane.”

In the 1700s, when Benjamin Franklin observed methane in the US, he described “inflammable air”. It was lighter than air and must have floated, flickered eerily in darkness. The gas, which was otherwise colorless and odourless, must have appeared otherworldly once it was lit.

Today, satellites have discovered previously unknown methane leaks from a landfill in Bangladesh; under melting permafrost in Russia; coal mines in the US; a natural-gas field in Canada. The single largest methane scavengers are cattle. Cows eat fibrous foods such as hay, and emit methane.

Under the sea-bed, under permafrost and under the ground, methane is ubiquitous and harmless. In today’s world of Climate Change, when leaked into the atmosphere, “it is one of the most potent greenhouse gases there is”, US President Joe Biden told the gathering of world leaders at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP26) in November. “It amounts to about half—half the warming we are experiencing today—just methane.”

The primary goal of COP26The Paris Agreement’s most important meeting on climate change was the. This meeting was to phase out coal and reduce carbon. The US declined to endorse it, as it had failed to pass domestic legislation. Instead, the US and the EU, two of the world’s five largest emitters, launched a joint Global Methane Pledge (GMP) on September 18, a few weeks before COP26.

Would enough countries join the US and Europe’s GMP to replace coal and meet global warming targets of limiting warming to 1.5° by 2050? Is it politically and technically feasible to make commitments to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030?

More than 90 countries had already signed the GMP by the time of COP26. China, Russia, and IndiaHowever, the US and Europe were not the largest methane emitters. Earth experienced its fourth warmest November in 142years.

Satellite Iris tracks methane, or “inflammable air”, the greenhouse gas which is the second largest contributor to the earth’s climate emergency

Satellite Iris tracks methane, or “inflammable air”, the greenhouse gas which is the second largest contributor to the earth’s climate emergency

Image: AFP

A few days afterwards, the US released a domestic draft ‘US Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan’, a five-point plan that outlines “critical and common sense steps to cut pollution and consumer costs, while boosting good-paying jobs and American competitiveness”.

It is still unclear if it will be enforced. Draft identifies methane emissions as being reduced in oil and natural gas, landfills and abandoned coal mines, as well as in agriculture, buildings, and industrial applications. Of these, agriculture is the highest source and is led by emissions from livestock: The dairy and beef industries. However, while most action plans are regulatory and binding, agriculture is merely titled “Incentive-based and voluntary efforts”.

A UNEP report re-confirms that “agriculture is the predominant source” of methane emissions. It details that “livestock emissions—from manure and gastro-enteric releases—account for roughly 32 percent of human-caused methane emissions”, which is “expected to increase by up to 70 percent by 2050”.

Andrea De Bono, head, Data & Information Sustainability Unit, UNEP/GRID-Geneva, who is “working on a platform for UNEP on climate change that will include time-series and geospatial maps” shared India-specific data on email. It indicates that India’s methane emissions have “more than doubled since 1950, from about 10,000 Gg [gigagrams] of CO₂eq to about 20,000 Gg of CO₂eq”.

A 2019 report of the Government of India’s Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying quantifies 535.78 million livestock animals, “an increase of 4.6 percent over Livestock Census 2012”. Similar to the US, most of these are cattle. In 2019, there were 192.49 million cattle in India, “an increase of 0.8 percent”.

Food systems and methane in the world are intertwined. This includes not only livestock but also humans. Water-intensive crops such as paddy require water.. When land is covered with water for long periods, methane is produced. These cropping patterns account 8% of human-linked emissions.

However, Dr Shyam Asolekar, Department of Environmental Science and Engineering at IIT-Bombay, explains, “Indian paddy growers do not have the luxury of continuous flooding because access to irrigation waters is limited.”

Indian solid waste has comparatively low biodegradable wet material. Biogas harvesting systems from garbage piles have produced very little biodegradable wet material.

Indian solid waste has comparatively low biodegradable wet material. Biogas harvesting systems from garbage piles have produced very little biodegradable wet material.

Image: Reuters

MethaneIt is highly inflammable. In 1776, Count Alessandro Volta (a close friend of Napoleon Bonaparte and after whom the electric ‘volt’ is named for his discoveries in electricity) read Franklin’s paper and observed similar “inflammable air” in the marshes of Angera on Lake Maggiore in the southern Alps in Italy. He discovered methane and tried to create energy.

Biogas is produced using processes that were first tested by Volta. The Government of India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) ‘National Policy on Biofuels’ aims to increase biogas production and reduce methane emissions through policies, capacity building, and public-private partnerships.

Landfills, which are located at the opposite end of the food spectrum, are the second largest source methane emitting countries. As co-author of the Report of the Task Force on Waste to Energy in 2014, which informed the Indian government’s Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, Asolekar studied two dumpsites in Mumbai and Ahmedabad. He explained that although biogas harvesting technology from landfills has been available for decades, “Indian domestic solid wastes have comparatively little biodegradable wet waste quantities. Dumpsites have waste mounds that tend to be dryer and more aerated. Biogas harvesting systems in garbage piles have only yielded miniscule amounts of biogas.” He summed up, “European or American landfills cannot be compared with the Indian waste mounds.”

Every bit of warming matters. A series UN Reports, from 2021 through COP26, were the basis for COP26. COP26Goals for net-zeRoThey were established. The first of them, in February, was ‘Making Peace with Nature’. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres had said, “Food systems are one of the main reasons we are failing to stay within our planet’s ecological boundaries”.

The October report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), contained dire warnings. A section on methane was headlined, “Agricultural emissions are increasingly driving near-term Global warming.” Methane emissions are “hundreds of times more potent” than Carbon dioxide in the climate crisis, “especially in the weeks and months after they are emitted”. The IPCC goes on to say atmospheric concentrations are “higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years.”

At the UN Food Systems Summit, Guterres reiterated, “Food systems hold the power to realise our shared vision for a better world.” Despite these, at COP26, he reiterated the primacy of cutting carbon by phasing-out coal and said, “On behalf of this and future generations, I urge you: Choose ambition. Choose solidarity. Choose to safeguard our future and save humanity.”

India is projected to be the most affected by climate change, sea-level rising and climate change. We will be experiencing more extreme-climate disasters in 2021. This includes droughts, floods, and cyclones. Many people lost their homes and livelihoods, and many more died.

Speaking after Guterres at COP26, Hoesung Lee, chairman of the IPCC report, presented his keynote address: “Make no mistake—it is a sobering read. It is a reflection of the global challenge facing all countries on the planet. Science shows that changes in the climate are widespread, rapid and becoming more intense and affecting every part of the world.”

Although controlling methane is a crucial way of limiting climate change, India, which is the fifth-largest emitter in the globe, has not signed the GMP and made no promises. We have no domestic plans to reduce methane emissions.

China, the world’s largest methane emitter, was absent and also did not sign the GMP. Still, without mentioning detail, it committed “to develop a comprehensive and ambitious National Action Plan on methane”.

Russia did not attend COP26 or sign any pledges, even though its Siberian climate, harsh enough to embody the nightmare of a man punishing himself for murder in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s classic novel Crime and Punishment, is under threat from the climate emergency. In turn, the methane exposed beneath Siberia’s melting permafrost will contribute and worsen climate change itself.

In the meantime, you can find the US’s own draft methane policyIt will be discussed within its borders and may, subject to domestic politics take effect in 2023. The US government is focusing on methane but they are unable effectively to address its largest contributor, especially livestock.

We look forward to the next climate convention, COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh (Egypt), in 2022. This is where political art takes center stage, over climate imperatives. The UN calls Code Red.

In the 1700s, Franklin could not have imagined that satellites would track his “inflammable air” in 2022. Satellites now do much more than that: They tell stories. Satellite Iris is high up in her orbit around Earth and tracks methane.

Even as she symbolises human heights of technological supremacy and control, Iris sends distress signals and tells stories of the Earth’s technology-driven climate emergency. We plan without commitment, but we praise our ingenuity to control natural forces.

The writer is the founder of Awaaz Foundation

Take advantage of our end-of-season subscription discounts with a Moneycontrol Pro subscription. Use code EOSO2021. Click Here for details.

This story appeared in Forbes India’s 14 January 2022 issue. Our Archives can be accessed here Click here)