[ad_1]

Akira Shimbo and Tiffany Shimbo were on Zoom work calls Dec. 14 when they heard a loud crash outside their Silverado Canyon home, a sylvan outpost located 45 miles southeast from Los Angeles. Akira ran out to the outside and saw a fast-moving stream of mud and water over their fence, pushing their Jacuzzi and garden beds into the Silverado Creek below.

“It sounded just like a car accident, only over and over,” said Tiffany Shimbo.

Tiffany pulled Akira through the window to safety while floodwaters and debris flows raged at their home on three sides. They waited three hours until the waters receded. The house stood, they and their 5-year-old daughter were alive, but they would soon learn that neither their insurance nor government disaster relief programs would help them.

The Shimbos, $15,000 in debt from grappling with 10 feet of mud and growing mold under their home and facing at least $75,000 in costs, are exploring filing for bankruptcy and selling their home to be demolished via a federal program.

“It’s heartbreaking,” said Tiffany Shimbo. “We knew we were at some risk. We just didn’t know it would be this severe and that no one would help. Because we live in Orange County, it’s one of the richest counties in the world, and how does someone not come and help?”

As climate change accelerates the destruction of nature, Americans are increasingly facing this outcome. The financial mechanisms meant to help disaster victims — private insurance and government relief programs — have never covered all the costs of disaster, but the pain is multiplying as the number of costly events in the U.S. rises swiftly.

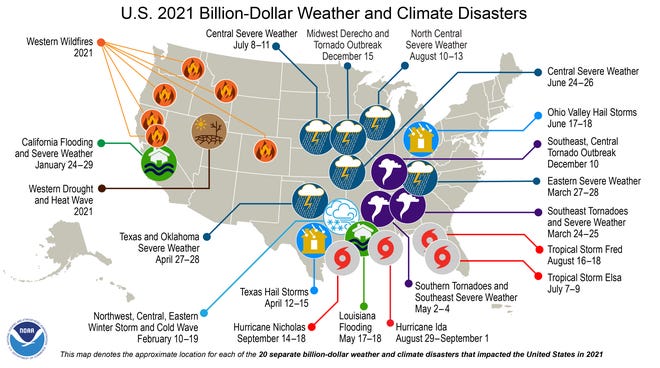

How fast? How quickly? Since 1980, the country had experienced seven of these disasters per year, adjusted for inflation. But in the most recent five years, the average spiked to more than 17.

These disasters can also kill; 688 people died in 2021, the highest death toll in a decade.

It remains to be determined how much climate change is responsible. However, scientists have linked global warming with many of the underlying conditions that lead to dangerous weather events, such as increased flooding and heatwaves and droughts. They also link more intense tropical storms to wildfires. This weekend Many were evacuated during a fierce wind-driven wildfire near Big Sur. Until a year ago, wildfires in January were largely unheard of in the Golden State, but longer, more frequent droughts are helping trigger year-round fires.

It’s not just major events that are on the rise. Carolyn Kousky, a disaster finance expert and executive director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Risk Center, said smaller events, like localized flooding, are also driving up costs.

Federal Emergency Management Agency claims data bear that out. The average annual payout for its flood insurance program was $89 million from 1980 to 1984, adjusted for inflation. However, costs have risen since then. In the past five years, the program has averaged just under $1.6 billion in annual payouts.

“There’s now widespread recognition that this isn’t a one-off thing, that we are on a trajectory of ever-increasing risk,” Kousky said. “We’re going to be seeing this and a lot worse in the coming years. This is not sustainable.”

When disaster strikes, there are typically four ways a home or business owner can recover, Kousky said: insurance, government relief, personal savings or a personal loan. The full cost of damage was not covered by disaster relief. And full insurance and personal savings are out of reach for many Americans.

“Savings and family aid are great for more affluent people, but a majority of Americans don’t have that kind of money to roll them through a disaster,” Kousky said. “Lower-income people struggle with all four of those sources.”

What makes matters worse now, said Jesse Keenan, a climate adaptation expert and professor at the School of Architecture at Tulane University, is that the increase in costly natural disasters is pushing beyond the country’s financial means to cope, from local governments to the federal budget.

The only way to solve the problem is through politically fraught systemic changes. He suggested that it would be better to identify high-risk areas and relocate residents, rather than relying on funds for rebuilding.

“There are a lot of political disincentives to dictate where people are going to live,” Keenan said. “But until we solve the land-use problem, no amount of disaster relief is going to fill the gap.”

Insurance without assurance

On a Friday night in early December, Ben Ashby was celebrating his 32nd birthday in Los Angeles when his phone began buzzing. Friends back home in Kentucky wanted to know: Was he in his cellar? Was he safe

About 2,000 miles east, a tornado had ripped through Walton Creek Valley, where Ashby’s family has lived for generations. The tornado was one of several on Dec. 10 that caused $3.9 billion in damage and 93 deaths across four states.

Ashby found his farmhouse standing three days later, but nothing else. A barn that his great-grandfather built was torn open, and other outbuildings were gone. An insurance adjuster told him $60,000 in damage to his house would be covered, but only about a third of $128,000 in damage to the barn and other structures would be paid out.

“One of them was my office,” Ashby said. “They haven’t even found all the walls of that yet.”

Ashby still counts himself among the fortunate. Friends and neighbors lost their homes, and Ashby said many weren’t insured enough to cover the full costs of rebuilding. Some people were told that they could receive as little as 20%.

“It’s insult to injury, because you think you’re protected,” Ashby said.

Experts who study the insurance industry say they understand those frustrations but point to an underlying truth: Many disasters are too expensive to fully insure.

“Will insurance, and even can insurance, ever completely provide coverage in a meaningful way for natural disasters? The answer to that is no,” said Donald Hornstein, a professor of insurance and environmental law at the University of North Carolina. “To do so would probably cause premiums to be so high as to be unaffordable.”

Hornstein said events like tropical storms present “correlated risk,” which means they can devastate wide swaths of policyholders, and wipe out insurance companies. Companies stopped covering floods after huge losses in mid-20th-century, which led to the creation in 1968 of FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program.

The program now provides more than 95% of all flood insurance policies in the U.S. But it has been billions of dollars in debt since Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, leaving taxpayers on the hook when Congress forgives the debt.

And many homeowners and business owners remain uninsured or underinsured by the program. The maximum residential coverage is $250,000, even though $400,000 was the median home sale price in the U.S., according to federal data.

Private insurance policies often exclude earthquakes and mudslides. Companies in the West are also dropping wildfire coverage.

Officials in California, whose 8.7 million insured homeowners make it the largest residential market in the nation, have tried to clamp down on private insurers shifting more expenses onto policyholders.

Major insurers cancelled residents’ policies within weeks after Paradise was completely destroyed by the 2018 Camp Fire. Companies cannot cancel customers who live in an area declared by the governor as a wildfire emergency. This ban was implemented by a state law.

Two more laws passed last year bulk up payments insurers must make for lengthy evacuations, lost clothes and other critical items, and forbid private insurers from deducting land value from a paid claim when a fire victim chooses to relocate — a move that companies previously used to sharply reduce payouts.

Companies can end policies at any time, even after the contract term has expired.

Homeowners in California’s high fire hazard areas often must now use the FAIR plan for fire insurance, a last resort pool created by state law to which all companies must contribute. Rates are higher. On Friday, the plan was expanded to include farms, winegrowers and ranchers, who are also experiencing more blazes.

Losses to insurers and citizens alike can be massive in wildfire-prone zones, and with climate change fueling ever more blazes, there’s a growing “disaster protection gap,” according to a 2021 California insurance task force report. The report found that wildfire losses in 2017 and 2018 totalled $45 billion. However, only $35 billion was covered. Insurers lost another $10 billion in those two years, another study found, though the state report said they recouped billions from power company PG&E, whose poor maintenance of electrical poles and wires sparked many costly blazes.

Whatever the policy, Hornstein said the insured value of a home specified in many may not meet real-world costs to rebuild it, especially with recent hikes in the costs of building materials. Customers might forget about updating policies.

What is the government responsible for?

Debris flows, also called mudslides, are another growing problem in the wildfire-scarred West, where rivers of mud, boulders and charred logs from burned hills can crash into homes during heavy rains.

The flows were predicted to affect 6.5 million acres in Arizona, California, Colorado and Nevada, New Mexico. But many homeowner policies also exclude mudslide or debris flow damage.

In Silverado Canyon, the Shimbos were told their FAIR plan claim was denied because they’d bought their property after the wildfire that created the mudslide conditions. The government can help if insurance fails. But there was no local or presidential disaster declaration after the mudslides to unlock public relief funds.

Orange County Supervisor Don Wagner, who represents the canyon, told USA TODAY that county attorneys saw the neighborhood debris flows as a private problem, not warranting the use of taxpayer funds beyond clearing public roads. A subsequent California emergency declaration means the supervisors may or may not now clear creeks and culverts with federal and county funds, but no dollars will go directly to residents.

To seal out the elements and remove the mud, the Shimbos relied on their neighbors and non-profits to attach plywood and tarps to their home. Like many Americans, insurance companies denied coverage. GoFundMe was started for them.

Others are also facing bills of up to $200,000 for foundation repairs and home repair. The community is now questioning the government’s ability to respond to natural catastrophes.

“We need to redefine, what is government responsibility?” said Linda May, a longtime Silverado resident who is also a former FEMA local fiscal chief. “The saddest thing, which I’ve heard so much on this disaster, is ‘Who’s gonna pay for it?’”

Experienced volunteers can help to push agencies to take action. In Orange County, Joanne Hubble, emergency response coordinator of a nonprofit called InterCanyon League, recalled that the Natural Resources Conservation Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, had cleared area creeks next to homes after debris flows in the wake of a 2010 wildfire. She reached out to them and showed them the affected canyon areas. The preliminary plans for 16 canyon projects are now complete.

‘Not a single penny?’

The shop on Main Street was supposed to be Chykeat Goodley’s ticket to the good life.

After 15 years of cutting hair and saving money, Goodley, 47, bought the three-story building in the small city of Norristown, Pennsylvania, with plans to open a barbershop and lease out other suites.

This was in 2020. The pandemic delayed its opening to March 2021. Six months later, the remnants of Hurricane Ida brought several feet of water into Goodley’s building, which he had just spent a year renovating.

Goodley’s insurer told him his policy didn’t cover floods, which hadn’t seemed necessary before Ida – his building isn’t in a floodplain. A FEMA representative informed him that Pennsylvania’s disaster declaration meant only a low interest loan. He didn’t have time for that. Any delay would have his tenants endangering their leases, a greater fiscal risk.

So, Goodley said, he threw $40,000 more savings and sweat equity into repairs: dry wall, floors, HVAC, electric. He feels blessed to have reopened, even though it set him back many years financially. Four months later, many other shops still remain closed on the street.

“At the time I thought government would help out,” Goodley said. “But not one thing? Not a single penny?”

Experts warn that relief programs from government agencies will not restore the lives of residents. FEMA help caps at about $37,000 for home damages. Other programs offer more to rebuild schools, roads, and flood control measures but can take years.

Using public funds to rebuild can also increase wealth inequities, said James Elliott, chair of sociology at Rice University. Research he did with colleague Junia Howell shows that 15 years after a disaster, white families’ wealth increases more than it would have had the flood or fire not occurred, while the wealth of families of color decreases more than expected.

Elliott stated that disaster aid funds often go to homeowners, especially those who have insurance. This leaves out renters and uninsured, who are more likely to have lower incomes and be less likely to be of color.

The Shimbos, an interracial family, bought an affordable, older home at Orange County’s rural edge, but she said they’ll likely be forced to rent an apartment if they have to abandon their house.

People with wealth and privilege are more likely to be able to navigate the public relief application process. Zack Rosenburg, co-founder of SBP, a national nonprofit focused on disaster recovery and resiliency, said FEMA can do much more to clarify application requirements and ensure funds are distributed equitably.

“It’s a process that … drives attrition by being cumbersome and complex,” Rosenburg said.

Anne Bink, associate administrator for FEMA’s Office of Response and Recovery, said the agency is working to improve.

FEMA has expanded the types and documentation it accepts to prove homeownership or rental status. Bink said this could impact families whose homes were passed down through generations. The change meant an additional 41,000 people were accepted for relief monies in 2021 who previously would not have been.

Bink stated that the agency is also working with U.S. Small Business Association in streamlining processes. A pilot project allowed 23,000 applicants to access assistance who otherwise would not have.

“We see this as a culture shift,” Bink said. “We know we have more work to do. … We want to continue to keep equity in the forefront of everything we do for survivors.”

$50 billion for’resiliency

Experts say that while there are ways to improve the country’s insurance and disaster relief programs, a holistic solution to the onslaught of climate change will require something bigger: getting out of harm’s way.

Although it is not popular, local zoning officials may “red tag” or deny properties that aren’t stable.

The California “climate insurance” task force in 2021 recommended devoting substantial upfront funds to making private properties and wildlands more “resilient,” such as enclosing eaves and better managing forests. Research shows for every $1 spent in advance, up to $6 in disaster costs can be avoided, they wrote.

They also suggested innovative ideas, such as the creation of community-focused insurance pools. It’s not clear who would pay. The idea was suggested based on a successful Nature Conservancy partnership with resort owners in Mexico who pay fees to preserve pristine natural spaces enjoyed by their clientele.

UPenn’s Kousky recently won a National Science Foundation grant to help pilot an alternative insurance model in New York City. It will finance a community organization to quickly deliver small amounts of money — say $5,000 — to low- and middle-income residents after flooding, easing immediate burdens for many.

But ultimately, experts say financial systems can’t cover the growing costs of disasters, nor should they. Historically, about half of the money paid out under FEMA’s national flood insurance program — more than $12.5 billion as of 2016 — went to rebuilding properties that repeatedly flooded, according to Pew Charitable Trusts.

Experts say that officials from all levels of government, including Congress, should adopt policies to limit building in floodplains or areas susceptible to wildfire. Instead of rebuilding, they should be paying to move people from those areas after disaster strikes.

The Shimbos are looking into it. Under another Natural Resources Conservation Service emergency watershed program, they may sell their home to the federal government to be demolished. Unlike FEMA, no emergency declaration is required, said Greg Norris, the agency’s California conservation engineer. He said the program is best known for buying out and tearing down homes in floodplains in the Midwest.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill signed into law late last year provides about $50 billion in climate resiliency funding, the largest ever such investment. Hornstein said the funds will boost federal efforts to relocate homeowners from floodplains or possibly elevate their homes and help pay for other flood mitigation projects.

Yet the money is just “a drop in the bucket,” Hornstein warned.

“The $50 billion is historic, and it’s simultaneously nothing,” he said. “The amount of money that actually needs to be spent is in the hundreds, and hundreds, and hundreds of billions.”

Janet Wilson is senior environment reporter for The Desert Sun, and co-authors USA Today’s Climate Point newsletter. Climate Point can be signed up for free in your email. Here: She can also be reached at [email protected]Or, @janetwilson66Follow us on Twitter

USA Today’s environment reporter Kyle Bagenstose is Kyle Bagenstose. He can be reached by email at [email protected]Or @kbagenstoseFollow us on Twitter

USA TODAY reporter Dinah Voyles Pulver and Ventura County Star reporter Cheri Carlson contributed to this story.

[ad_2]