[ad_1]

O24 October 2019, Maura HEADLEY, the attorney general for Massachusetts, ExxonMobil sued for “deceptive advertising” and for “misleading Massachusetts investors about the risks to Exxon’s business posed by fossil fuel-driven climate change”. It was the culmination an investigationHealey began investigating Exxon’s alleged misinformation about climate in 2016, decades after the company’s scientists had briefed it on the issues.

This week the Massachusetts supreme court is hearing arguments related to that case – but not about Exxon’s actions decades earlier. Instead, the oil company wants to see whether Healey violated the first amendment rights of the suit by bringing it in the first instance.

With all of its other legal options exhausted, Exxon’s efforts to stop this case hinge on the one last complaint: invoking Massachusetts’ anti-Slapp statute. Slapp stands as Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation. The statutes against such legal claims were created to protect journalists and civil society groups from corporations who want to silence critics. In recent years, however, it’s become increasingly common for corporations to invoke anti-Slapp laws instead to protect TheyFirst amendment rights

In US climate litigation, the anti-Slapp argument is a popular strategy. In some two dozen climate liability cases, in which counties, cities and states are asking oil companies to pay their share of climate adaptation costs, the oil company defendants have argued that their public statements about climate change were not “deceptive” so much as persuasive. They describe their ads, op-eds and public appearances discouraging climate action as “petitioning” statements, turning them into political speech that is protected by the first amendment.

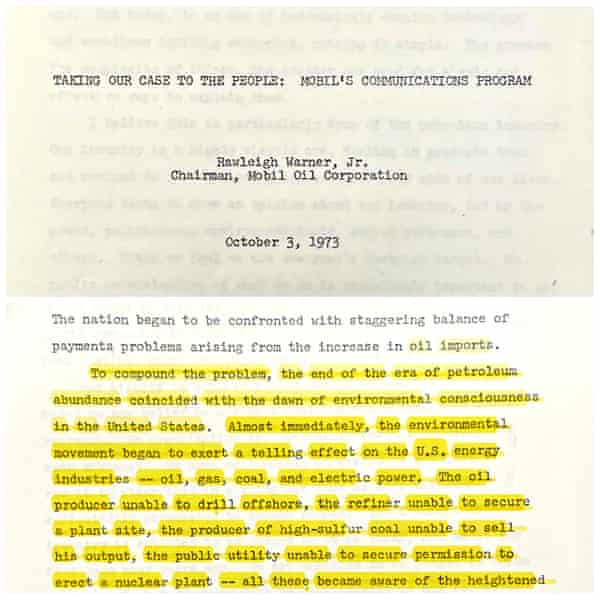

Never published before Documents internalMobil Oil reveals that corporate executives established the framework for corporate free speech in the late 1960s/early 1970s. The argument arose out of a situation not unlike the one playing out today, with war driving up prices at the pump and oil companies wanting desperately to change the public’s perception of their industry.

The longtime Mobil VP of public affairs, Herbert Schmertz, and then CEO, Rawleigh Warner, came up with an idea to help them wrestle back control of the narrative and win over the public: using Mobil’s PR and advertising budget, they would create “idea advertising”, also known as “issue” or “advocacy” advertising, to push the company’s take on key issues of the day and to create the sense of Mobil as a citizen, with a distinct personality.

In a 1971 strategy document explaining the reasons for this approach, Schmertz wrote: “We expect consumers increasingly to factor their notions of a company’s social responsiveness into their decisions about buying its products and stock.” In An interview about the strategy a few years later Schmertz explained, “Legislation does not develop in a vacuum. It develops from public attitudes and mirrors public beliefs. When it comes to matters of energy, the oil industry tends to be viewed as the villain.”

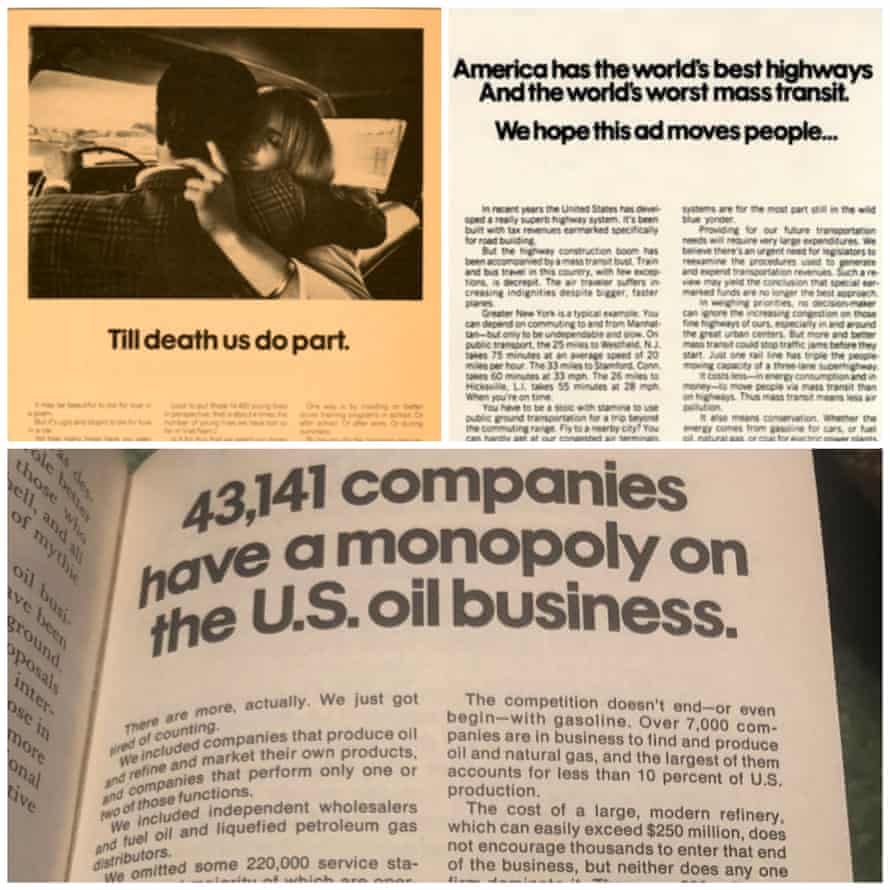

By 1970, Mobil began running weekly advertorials in the New York Times presenting the company’s point of view and, as Schmertz put it, “trying to explain the energy industry to the American people”. But the ads weren’t just policy stances – Mobil also used the space to develop what Schmertz called its “corporate persona”, where the company openly supported everything from public transit to the arts and educational programs.

Mobil also funded programming on PBS at the same time. It started with the very popular Masterpiece Theater. Within just a couple of years, the company was running polls that showed consumers were starting to think of Mobil as the “thinking man’s oil company”.

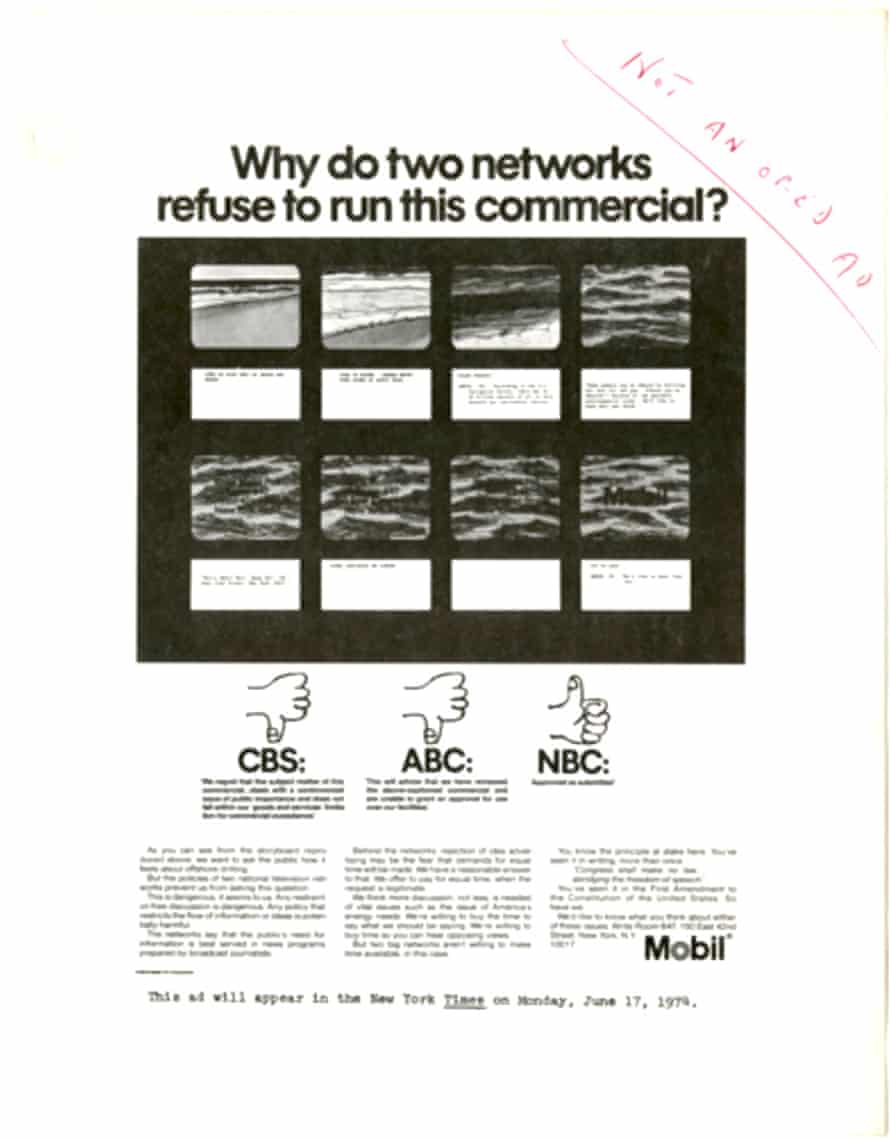

However, the company was not able to convince network TV stations with much success. CBS and ABC refused to run visual versions of Mobil’s advertorials, saying they preferred to let their journalists cover issues of importance to the public. This response prompted Warner and Schmertz to launch a long-running campaign for corporate free speech and the need for it to be protected. The Guardian obtained letters from two oil executives to newspaper editors and TV executives, as well speeches to various pro business clubs. They repeatedly claimed that protecting corporate free speech is equivalent to protecting democracy.

Warner blamed environmentalists for the industry’s woes, their need to speak out, in speeches to the Economic Clubs of Chicago and Detroit too.

“We contend that the inherent limitations of broadcast news, especially time constraints, lack of expertise in energy, and programming formats, act against accurate and in-depth coverage of energy, and other complex, major issues,” Schmertz Submitted Arthur Taylor, CBS president, 1974. “The obligations of network news to the public go beyond fairness and objectivity. They should promote a free flow of information and opinion on major issues to the public.”

The same year, in a talk at the annual convention of the Edison Electric Institute, which would go on to be a major purveyor of climate denial in the 1980s, Warner warned: “We are in no sense eager to stifle those who oppose us. It is the opposite. We just want to be heard, too.”

Robert Kerr, media law professor at the University of Oklahoma’s Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication, has researched corporate free speech and Mobil’s role in crafting the idea for decades. “This whole argument that the corporate voice was being silenced is just the opposite of the truth,” he said. Kerr adds that by virtue of having more time, people and funding than any individual and most groups, corporations “could always get their views out better than the average person by manyfold”.

However, Warner and Schmertz sensed a threat in 1970s. While Mobil never filed a case of its own to defend its “free speech” rights, it did begin filing amicus briefs in other corporate speech cases, and encouraging other pro-business advocates, like the US Chamber of Commerce, to do the same. The company also continued to regularly make the case in the court of public opinion via its weekly advertorials in the New York Times and its executives’ regular appearances on radio and TV.

Mobil’s efforts to get the business community to speak out against corporate speech in the 1970s culminated with Citizens United’s first major supreme court case. First National Bank v Bellotti. The case was a precursor to Citizens United’s 2010 ruling, which opened the floodgates for corporate spending. The 1978 ruling by the court allowed corporations to spend whatever money they like to influence politics. It overruled a Massachusetts statute. In the ruling, Justice Lewis A Powell said, “If the restricted view of corporate speech taken by the Massachusetts court were accepted, government would have the power to deprive society of the views of corporations.”

Citizens United blurred the line between commercial speech – a marketing message from a company to the public – and political speech, which up until Citizens United was connected only to funding or speech backing a particular candidate or policy. OilFor years, companies have tried to destroy that line. The current batch of climate cases is the latest example of their efforts.

In Massachusetts this week, attorney Justin Anderson, a partner with Paul, Weiss, ExxonMobil’s law firm, argued that the state attorney general’s fraud complaint against Exxon was not valid because the company’s public statements on climate policy should be considered as political opinion, not misleading advertising – even when Exxon falsely claimed that climate change isn’t real.

When asked why they would opt to file an anti-Slapp complaint rather than make a direct first amendment argument in court, Anderson made it clear that the point is to avoid discovery – the period of time in a civil case when corporations are asked to hand over files and make their executives available for depositions. “The anti-Slapp statute provides a mechanism to have a case that is brought against someone for petitioning activity dismissed at the outset before burdensome discovery is imposed on the party,” he argued.

Legal observers believe that the oil companies’ response to the climate cases tees up the likelihood of the next big supreme court case on corporate first amendment rights.

“They will try to defend their misinformation efforts as political speech covered by the first amendment and not subject to false advertising laws,” says Robert Brulle, an environmental sociologist who has co-authored briefs in some of these cases.

Kerr agrees, although he notes that to side with the oil companies’ arguments in these cases, the supreme court would have to turn its back on about a century’s worth of legal precedent. “It’s really deeply established even by some of the members of the current supreme court, that the first amendment will never protect expression that is fraud,” he said. “The worry now is that with this court there seems to be a majority that wants to say yes to almost any question the corporate interests raise. And I hope I’m wrong about that. I hope this is a line they won’t cross.”