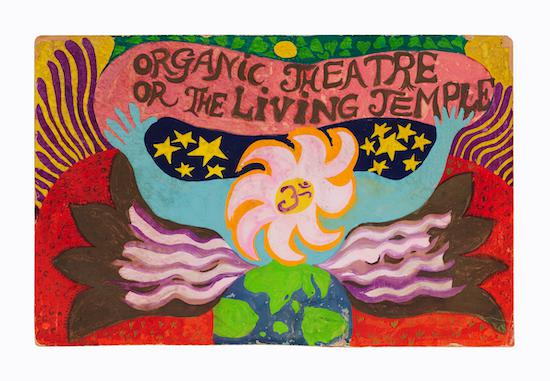

Moki Cherry. Organic Theatre or The Living Temple. 1972. Courtesy the Estate Moki Cherry, Tgarp (Sweden) and Corbett Vs. Dempsey (Chicago). Photo by Tom Van Eynde

Moki Cherry. Organic Theatre or The Living Temple. 1972. Courtesy the Estate Moki Cherry, Tgarp (Sweden) and Corbett Vs. Dempsey (Chicago). Photo by Tom Van Eynde

Moki Cherry, the wife of Don Cherry, wrote Randi Hultin on Tuesday, 3 September 1968: Thank you for the pictures and cuttings. We are sending you the following material from last night’s concert, in the hope that you will be able help us come to Oslo.

It will be wonderful to remain some time before, Moki continued, to rehearse, and work in a new environment. We would also like to learn more about possible dancers (Karin Krog?) Yes, so many ideas.

This word environment is a clue to the direction Don and Mokis’ performances will take over the next few year. It goes away from the more straight-forward presentation of Cherrys music at a familiar concert setting, and instead focuses on environmental activism and multimedia performance. These would include brightly coloured psychedelic paintings and tapestries as well as canvases. They would also be known as Movement, Organic Music Theatre, and Organic Music Theatre.

The letter is on display in Bergen Kunsthalls exhibit File Under Freedom. It is a work-of-art in itself. The cursive lettering weaves around Mokis drawings, which include stars, clouds, and the sun. Several sentences are arranged to radiate from the sun like light beams. She signs off with a sketch showing Neneh (4 years old) and Lanoo Eagle Eye (4 months).

We see images of swans, dragons, and other creatures on vivid canvases. A bulbous hanging foam sculpture that resembles the contemporary soft sculptures Yayoi Kusama and the udders a patchwork cow. Also, pictures of Don and other musicians lying on blankets on the grass at Molde International Jazz Festival 1968, playing their flutes, and generally enjoying the bright Nordic sunshine.

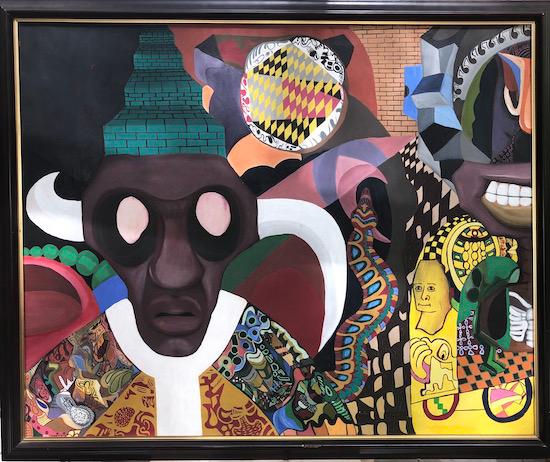

Milford Graves. Hand-painted drums. Image courtesy Artists Space in New York and Ars Nova Workshop in Philadelphia. Filip Wolak

Milford Graves. Hand-painted drums. Image courtesy Artists Space in New York and Ars Nova Workshop in Philadelphia. Filip Wolak

Don Cherry had visited Norway before Mokis letter in 1967. We see him with Jan Garbarek, a neatly coiffed Norwegian who is seated beside Cherry on his saxophone. Cherry’s trip to Norway in 1967, according to Steinar Sekkingstad (Kunsthalls curator), was a pivotal moment for the development of the Scandinavian jazz scene and also for the countrys visual arts.

We can see a monitor showing an older film that was made for Norwegian television around the same time, across the hall, from the bright, particoloured Cherrys photos, and Mokis visual artwork. LydbilderThe music of Garbarek is used as the soundtrack for a long pan through a series of paintings and collages by Sidsel Paaske, an Oslo-born artist. The walls are adorned with more of Paaskes’s amazing work. Paaskes’ expressive lines and repeated motif make sounds seem to leap from the pages. Some of these motifs recall the sunbeams in Moki Cherries letter to Hultin.

Roscoe Mitchell told me that I develop my themes in paintings the same way as I develop my music when I interviewed him at last weekend’s Borealis Festival in Bergen. It is possible that there is a secondary thesis you could File Under Freedom. The same impulses, processes of thought, and imagination underlie both the explosion of creativity that arose from improvised songs in the late 1960s or early 1970s and the visual art that emerged from the exact same milieu.

The Kunsthall walls are lined with Mitchells paintings. They have a remarkable continuity. Hi PanoplyFrom 1966, it looks like an explosion of city blocks with sharp, clear lines like skyscrapers that run parallel to florid patterns that resemble Nigerian ankara prints fabrics. Cartoonish faces at right angles are made from marshmallow colours and poke out of foam-like splotches. The more recent Inner Worlds(2020) has a similar energy. It contrasts sharp diagonals with dots, curves, and is now rendered in a more lysergic, day-glo palette.

Roscoe Mitchel, The Third Decade, 1970. Oil on canvas, fabric and wood. With fringe. Image courtesy of the artist. Wendy L Nelson

Roscoe Mitchel, The Third Decade, 1970. Oil on canvas, fabric and wood. With fringe. Image courtesy of the artist. Wendy L Nelson

Peter Brtzmann’s three cloud sculptures, however, are decidedly dun. They look like little wooden boxes with cut-outs made in browns and grays, with some odd quasi-mechanised details. The earliest are Sound CloudThe 1970s-era image ”, with its lumpen metal clod peeking out from a charcoal-coloured background, looks like scorched wood.

Brtzmanns stark simplicity is in sharp contrast with six Matana Robs works. These works feel almost like scraps of a diary or a more agitated, angry riposte at Aby Warburgs. Mnemosyne Atlas. Old photos are covered in thick smudges black and grey, bits of music manuscript, plastic wrap, newsprint and a stamped CND logo. In one work, a painted cassette is stuck to the board with a torn postcard about the Mississippi river levee. These works are similar to Roberts music in that there are layers upon layers, of historical reference and montaged meaning, and they are assembled with the same care and finesse as Roberts music. Coin Coin records so enchanting.

The final room features a film directed by Eric Baudelaire that tells the story of Alvin Curran. Curran speaks out about meeting Franco Evangelisti (an Italian composer) of Gruppo di Improvvisazione nuova Consonanza. Curran was in the midst of his twenties, while Evangelisti was around forty. It’s clear that the American composer regarded Evangelisti older than Curran and considered him one of the most important composers of his era. Franco Evangelisti said to me when I met him, “You’re a composer, right?” Is it not true that there is no more music to create? I didn’t realize there was no more music.

The news was shocking. Curran described feeling like he was near the end of music, and he decided to form the improvising band Musica Elettronica Viva along with Frederic Rzewski. The bright suns and vibrant swirls of Moki Cherries letters, tapestries and paintings hint at another motivation for avant-garde music’s creative explosion. It’s not the apocalypse, but perhaps there’s more hope.

File Under Freedom is at Bergen Kunsthall (Norway) until 27 March 2022