[ad_1]

This article was originally published at World Resources Institute. It’s available here.

In his first week in office President Joe Biden Established the Justice40 Initiative, which aims to deliver 40 percent of the overall benefits of federal climate and clean energy investment to disadvantaged communities across the United States. This initiative promises to provide long-overdue and urgently needed financing for a clean energy transition, which contributes to redressing economic and environmental injustice.

A systemic and long-standing discrimination on the basis of income, race, ethnicity, and income has resulted in a limited availability of economic opportunities, disproportionate pollution of the environment, and an increased vulnerability to climate changes for certain U.S. communities. These communities face multiple, complex and compounding forms of disadvantage and vulnerability. Climate policy and public spending can help to address these issues.

However, there are historical and ongoing social, environmental, and economic factors Inequities in the country, the benefits and costs delivered by the low-carbon transition are likely to be inequitably distributed without strong interventions across levels of government.

It will take a fair and equitable transition to clean energy to achieve justice. policies that ensure investments and benefits are distributed in a way that addresses decades of underinvestment and marginalization in disadvantaged communities that face distinct and varied socioeconomic and environmental challenges.

The White House Council on Environmental Quality released a beta version of its Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) in February 2022.

The White House Council on Environmental Quality has released a beta version to assist federal agencies in implementing the Justice40 Initiative by identifying disadvantaged neighborhoods. Climate and Economic Justice Screening tool (CEJST) in February 2022. These communities are identified by the tool. Eight categories of indices for disadvantaged status — related to underinvestment in energy, transit, workforce development, housing, water infrastructure and more. Each category also has its own topical indicators that show different types of economic, environmental, and social burdens.

Federal agencies are likely to be the main users of CEJST. These agencies will use the tool for federal investments in climate change and clean-energy programs for disadvantaged communities. The tool can be used by state and local policymakers, industry, and community organizations to address environmental justice issues.

New WRI analysis uncovers insights about the disadvantaged communities this tool is intended to serve.* Here’s what we know:

1. Nearly 29 per cent of the US population (93.5 Million people) has been identified as being disadvantaged. This group faces inequity across many socio-economic, climate, and environmental indicators.

For perspective, that’s more than 1.5 times the estimated population of the northeast, and almost five times the population of New York. These communities can be found in all 50 states and Puerto Rico. In fact, 75 percent of U.S. county’s contain at least one disadvantaged community.

This population is made up of diverse communities that share common challenges and characteristics. On average, disadvantaged communities experience twice the traffic volume and proximity that non-disadvantaged communities. They also have greater health risks, such as higher rates of asthma and coronary heart disease.

On average 53% of the population in disadvantaged communities lives below 200% of the federal poverty line, compared to a non-disadvantaged average of 23%.

Disadvantaged communities are faced with significant financial security challenges. The average household income in a disadvantaged neighborhood is approximately $47,300, while that of a nondisadvantaged community is about $93,800. In disadvantaged communities, 53 percent of residents live below the poverty line. 200 percent of federal poverty lineThis compares to a non-disadvantaged average 23 percent. Finally, the disadvantaged communities tend to be younger than the non-disadvantaged average of 23 percent. This indicates that legacy pollution can be addressed and the benefits will last a lifetime.

The graphic below shows the diversity of metrics used to identify disadvantaged areas and the number of people who were affected by the difficult circumstances these metrics track.

2. Geographically, disaffected populations are concentrated in certain areas rather than being spread evenly across the country.

The percentage of the state population living in disadvantaged areas ranges from 52 to 5 percent in Mississippi (see graphic below). The number of people who live in disadvantaged areas in the South, including Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, is high. This is not surprising considering that different metrics of disadvantage tend to be clustered based on historical context.

Communities such as the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia and areas near Texas-Mexico border have a long tradition of having a history of High levels of racism and pollution. These areas also have limited economic opportunities, which creates conditions that last over time.

These deep-seated structural inequalities must be addressed. Federal investment in climate change and clean energy programs should not be spent in ways that encourage racialized economic and environmental discrimination. In order to ensure equitable implementation of programs, the federal government should also strengthen the capacities of local governments, states, and community groups. This will require consistent and collaborative engagement between the federal government and these specific states — like Mississippi, West Virginia and New Mexico — to support and monitor the equitable use of climate and clean energy funding.

3. Rural areas are more vulnerable to being disadvantaged.

80 percent of census tracts in the U.S. that have been identified as being in disdisadvantaged communities are in urban areas or in urban counties, compared with 20 percent in rural areas. This large disparity is due to the fact that census tracts are more densely distributed in urban areas than in rural areas. 38% of rural census tracts are deemed disadvantaged and 30% are located in urban areas.

Similar trends are observed in terms of population. 27 percent and 37% of the population respectively in urban and rural census tracts have been identified as being disadvantaged. The percentage of rural residents living in disadvantaged areas is greater than 50 percent in 14 states (see graphic below). This includes Mississippi, for example, where 68 percent of the state’s rural population are in disadvantaged communities compared to 38 percent of its urban population.

Climate change will compound the inequities present in rural communities — in particular by increasing the volatility of agriculture, forestry and natural resource-dependent sectors on which rural communities are dependent. Solutions for climate change in rural areasThis can address both the climate crisis as well as the low economic vitality of many rural communities. It includes massive expansions in wind and solar energy, environmental remediation and tree restoration, as well a massive increase in wind and solar power.

4. Although CEJST implicitly considers the impact of race when identifying disadvantaged communities, explicitly including race in the tool would acknowledge the central role that race and racism play in creating disparities among communities.

Environmental justice advocates have criticized CEJST for not including race as an indicator of identifying disadvantaged populations. Despite the fact there are numerous studies (see Here, Here and here) have shown that race is the most important predictor of the distribution of environmental hazards. The Chair of CEQ has noted that the use of race-neutral criteria will enable the tool to survive legal challenges, while the inclusion of indicators — such as proximity to hazardous waste facilitiesAnd high exposure to diesel particulate matter — act as a proxy for race.

The data bears this out. Even though race is not explicitly included, the tool identifies that Black, Latino, American Indian and Alaskan Native individuals are disproportionately disadvantaged.

Even though CEJST is implicitly accounting for the disproportionate disadvantage faced by Black, Latino and Indigenous communities, as well as other communities of color, and tHere are legitimate concerns about the Legal challenges that a tool integrating race might face, there are real arguments for including race as an indicator. Recognizing the role of racism and race in creating and reinforcing inequitable distributions of health, housing, and economic costs would be a way to acknowledge their contribution. It is essential to identify the root cause of existing disadvantage in order to prevent inequitable investment in disadvantaged areas.

CEJST might be able to identify a community with a large non-white population that is polluted and faces related health problems. But if the government doesn’t regulate the pollution from existing facilities and infrastructure, as well as the racist zoning/development practices that contributed to the current situation, then spending in this community may not solve these problems. It could lead to the perpetuation or worsening of existing injustices and creating new inequities through the unmanaged growth and clean energy economy. This is because it prioritizes the safety and health of white communities.

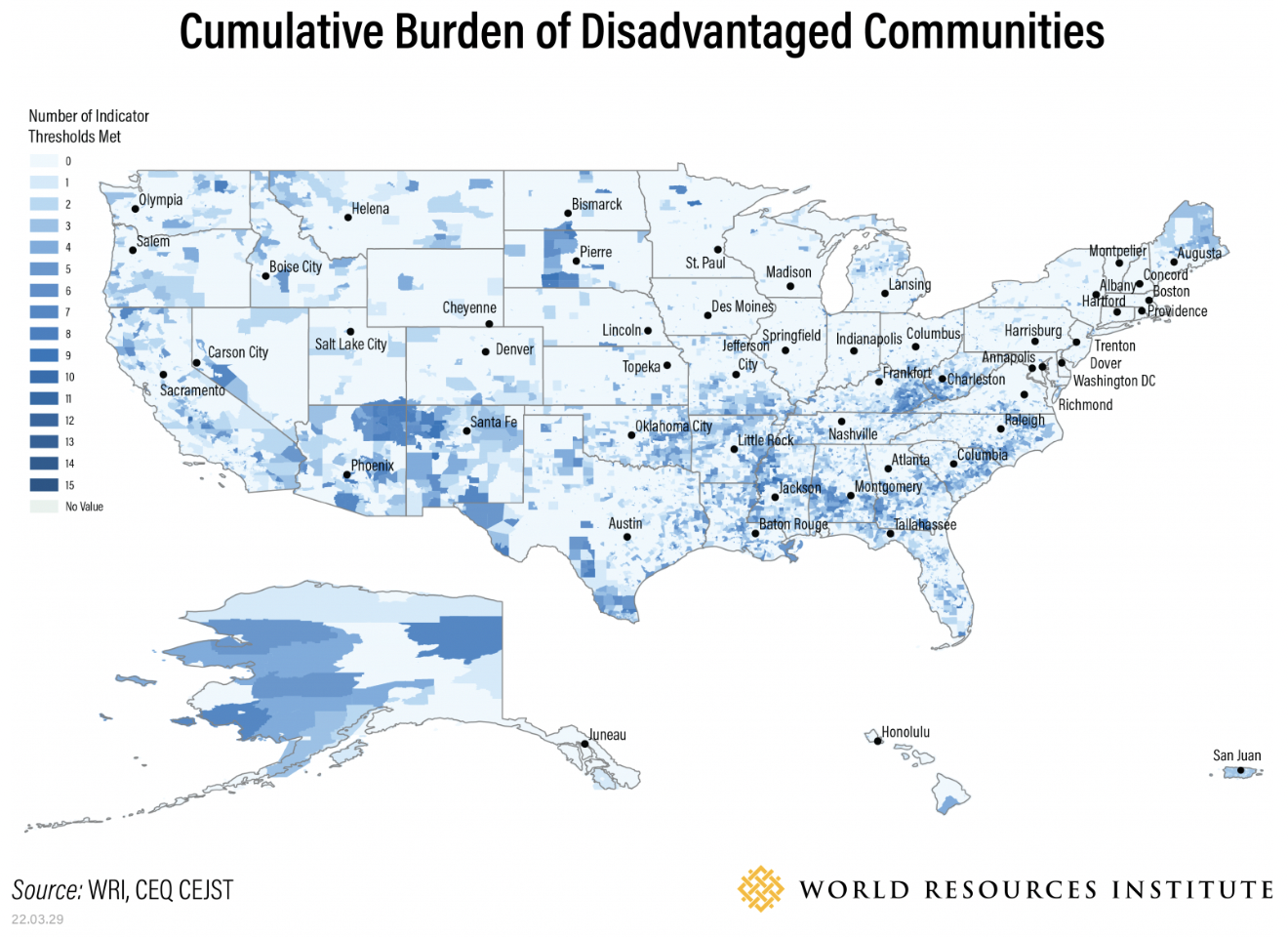

5. Within the category “disadvantaged,” there is significant variation in the types of disadvantage each community faces, and in the cumulative burden.

CEJST, as currently designed, doesn’t allow for examining the cumulative burden of socio-economic, health and environmental indicators. It examines each of the eight categories separately and determines if a community meets any threshold in any of the eight categories. and meets the low incomeAnd higher education enrollment rate threshold, it qualifies for disadvantaged community classification.

The resulting disadvantaged communities can be any of the following: those that meet the threshold only for one indicator (from the 21 contained in the eight categories) to those that meet 15 different indicators (see graphic). Nearly 79 per cent of the population lives in census tracts that meet the thresholds for five or fewer indicators. About 1 million people reside in the 2 per cent of communities that have 11 or more indicators. This group is most affected by the interactions between individual indicators.

This variation highlights the importance of policymakers changing CEJST to better serve disadvantaged populations by incorporating a cumulative impact approach. The approach adopted by CalEnviroScreen which provides a statewide assessment of cumulative impacts across communities in California. Federal agencies that use this tool must consider the specific dimensions of risk they are able address, not just the disadvantaged status of a community, in order to ensure that funding goes where it is needed. A realistic assessment of the cumulative effects of various stressors in communities is essential to solve long-standing health and environmental problems.

6. TIndicators of climate risk that are forward-looking could be misleading and underestimate climate change vulnerabilities.

The tool uses historical data about natural hazards and losses to assess vulnerability. It considers past events as well as the severity of their damage, and weights more recent years. These hazards can exacerbate existing inequalities by affecting low-income and minority communities. More exposed to risks and documented racial disparities in the administration of recovery funds. As extreme weather events become more frequent, intense, and impact wider swathes, it is important to rely on historical data. This will not provide an accurate picture of the most vulnerable communities.

The national median of agricultural yield declines by county in a severe climate scenario is 20 percent. This is the scenario that is most likely to occur (graphic below). The 459 counties currently considered disadvantaged due to agricultural risk are 8 percent above the 90th percentile. Yields are expected to drop more than 45 percent in the future for these counties. Another 158 counties presently identified as disadvantaged but not due to agricultural criteria join the 90th percentile for future losses, indicating that for some of those at risk the risks get much worse.

52 counties are currently home to no disadvantaged community that is above the 90th percentageile for future agricultural losses. This indicates regions of significant risk that are not being considered in current assessments. There are several counties in Nebraska, Missouri and Kansas that are likely to suffer severe losses but do not meet the current agricultural risk threshold. This is why it is important to factor in future-looking climate risks indicators. Communities that aren’t already vulnerable could become so in the near future, and communities that are already at risk in certain dimensions may be made more vulnerable as the effects of climate change increase.

Opportunities to get involved and more to do

Although the CEJST offers a unique lens to understand and identify patterns of underinvestment, marginalization, and disadvantage across the U.S., there are still many questions about its effectiveness and accuracy. This tool is still in beta. CEQ actively seeks feedback. This public review period will allow experts, implementers, stakeholders, and communities to evaluate the tool and provide feedback. It will also highlight important procedural and substantive areas for improvement.

CEJST may prove a useful tool in targeting federal spending and engagement efforts, however it’s important to note that this is only one singular, quantitative measure of need and only one perspective on how to target climate and clean energy spending equitably. It is possible to make the tool more useful by incorporating local and sector-specific considerations, insights from stakeholders, as well as learning, feedback, and continuous improvement.

While data and screening tools, such as CEJST, can be helpful, it is equally important to have strong and intentional community engagement and empowerment. This empowers communities to identify their needs, and then invests in co-created solutions for local economic, social, and environmental problems.

*All analysis is based on the February 18, 2022 data set downloaded from the Beta CEJST. The complete data set includes all census tracts from outside the 50 States. Projected data for the U.S. were not available to aid in the analysis of future climate impacts. Territories were therefore not included in the forward-looking comparison.